No Decay, No Defeat: What It Means That Christ’s Body Saw No Corruption

On the Day of Pentecost, Peter stood before thousands and made a startling claim: David’s body decayed in the tomb, but Christ’s didn’t. This was no throwaway detail. Peter staked the entire Christian message on it. Why? Because the body that didn’t decay tells us something profound about Him who was in that tomb—if only briefly—and about the victory He won for us.

When Scripture says Christ’s body would not “see corruption,” it’s making three connected claims: He was sinless, His death and resurrection were certain, and our own glorification is guaranteed. Let’s explore what the apostles and the Reformed tradition teach us about this vital truth.

THE PROPHETIC FOUNDATION

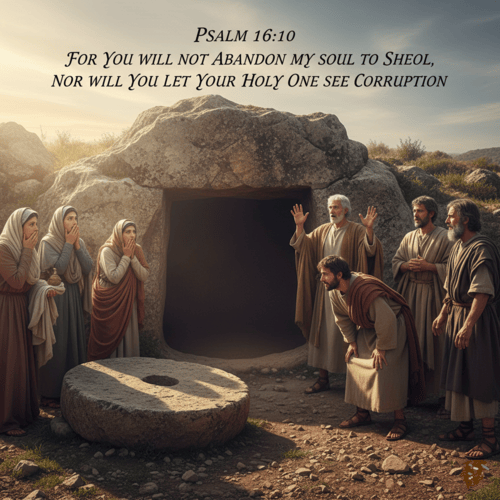

The promise appears first in Psalm 16:10: “For you will not abandon my soul to Sheol, or let your holy one see corruption.” David wrote these words with confidence, yet David’s own body did decay. His tomb was still in Jerusalem (Acts 2:29). Clearly, then David wasn’t speaking about himself—he was prophesying about the Messiah.

Peter makes this explicit at Pentecost. Quoting Psalm 16, he declares: “Brothers, I may say to you with confidence about the patriarch David that he both died and was buried, and his tomb is with us to this day. Being therefore a prophet…he foresaw and spoke about the resurrection of the Christ, that he was not abandoned to Hades, nor did his flesh see corruption” (Acts 2:29-31).

Paul uses the identical argument (Acts 13:34-37). For the apostles, this wasn’t minor evidence—it was proof positive that Jesus was the promised Messiah.

The Westminster Larger Catechism (Q. 52) explains that while Christ truly experienced death as part of His humiliation, His divine nature prevented His body from decaying. Real death, yes. Corruption, no.

WHY NO CORRUPTION?

To understand why Christ’s body didn’t decay, we need to grasp what corruption actually is. Physical decomposition—the body returning to dust—entered the world through sin. “You are dust, and to dust you shall return,” God told Adam (Genesis 3:19). Death and decay are the wages of sin (Romans 5:12). Every corpse that decomposes bears witness to humanity’s fall.

Here’s the logic: If corruption is sin’s consequence, and Christ had no sin, then corruption had no rightful claim on His body. As Paul writes, He “knew no sin” (2 Corinthians 5:21). Hebrews declares He was “without sin” (4:15). Peter testifies He (Christ) “committed no sin, neither was deceit found in his mouth” (1 Peter 2:22). The Heidelberg Catechism (Q. 41) emphasises that even in His humiliation, Christ remained “true and completely righteous.”

Think about it: If Jesus’s body had corrupted in the tomb, it would suggest sin had a legitimate claim on Him. But sin had no such claim. His body—conceived by the Holy Spirit, never tainted by personal transgression—could not justly undergo the curse of corruption.

Francis Turretin adds another dimension: Christ’s human nature remained united to His divine nature even in death. This hypostatic union (the theological term for the joining of Christ’s two natures in one person) meant His body was divinely preserved from decay. This wasn’t a denial of real death—Jesus truly died. But His body remained under divine protection even in the tomb.

WHY THE APOSTLES MADE MUCH OF IT

Peter and Paul didn’t mention this detail for historical trivia. They weaponised it. In a world intimately familiar with death and decay, everyone knew bodies decompose quickly, especially in warm climates. A body not decaying over three days pointed unmistakably to supernatural intervention.

This truth served multiple purposes.

- It proved Christ’s death was real—no swoon theory, no fake death (against early docetic heresies that claimed Christ only appeared to die).

- It demonstrated His sinlessness—corruption would have indicated sin’s rightful claim.

- It showed divine approval and power—God vindicated His Holy One.

- It fulfilled specific prophecy—here was Psalm 16:10 before their eyes.

- Most importantly, it distinguished Christ’s resurrection from mere resuscitation. Lazarus was raised but later died and decomposed. Jesus was transformed. Death no longer had dominion over Him (Romans 6:9). This wasn’t a temporary reprieve from death but death’s total defeat.

WHAT THIS MEANS FOR US

Christ’s incorruptible body isn’t just about what happened to Him—it’s about what will happen to us.

- It assures us of Christ’s complete victory. Because His body didn’t corrupt, we know death’s power is broken. The grave couldn’t hold Him.

- It’s the pattern for our resurrection. Paul writes: “What is sown is perishable; what is raised is imperishable” (1 Corinthians 15:42). Our bodies are “sown in corruption” but will be “raised in incorruption.” Philippians 3:21 promises Christ “will transform our lowly body to be like his glorious body.” Because His body didn’t corrupt ultimately, ours won’t either.

- It grounds our justification. Romans 4:25 says Christ “was raised for our justification.” His sinlessness—proven by no corruption—means His righteousness is truly imputable to us. We’re declared righteous in the Righteous One who conquered death.

- Finally, it gives us hope in death. Turretin’s pastoral point rings true: while our bodies may decay temporarily, we’re united to Him whose body did not. Our resurrection is as certain as His.

THE VICTORY STANDS

The detail that Christ’s body did not see corruption wasn’t a footnote in apostolic preaching—it was foundational. Prophecy foretold it. The apostles proclaimed it. Theology explains it. And we benefit from it.

When we confess “the resurrection of the body,” we’re echoing the apostolic confidence that corruption will not have the final word. We serve a sinless Saviour who truly died, truly rose, and whose victory over decay guarantees our own. The absence of decay in His tomb means there is no ultimate defeat for His people. That’s a truth worth celebrating.

RELATED FAQs

Did Christ’s body experience any change at all during the three days in the tomb? Reformed theologians agree Christ’s body remained truly dead but divinely preserved. John Calvin emphasised that while Christ’s body and soul were genuinely separated (as at real death), God supernaturally prevented the natural processes of decay from beginning. The body didn’t improve or transform in the tomb—that happened at the resurrection. But neither did it deteriorate, because corruption is a consequence of sin’s curse, and Christ bore our sin’s penalty without being subject to sin’s natural effects on His sinless flesh.

- How quickly does a body normally begin to decompose, and why does this matter? In the warm climate of first-century Jerusalem, decomposition begins within hours, with visible signs appearing within 24-48 hours. By the third day, the process would be unmistakable—which is likely why Martha protested when Jesus approached Lazarus’s tomb on the fourth day, saying “there will be an odour” (John 11:39). This makes Christ’s incorruption even more remarkable: His body lay in the tomb from Friday evening through Sunday morning—roughly 36-40 hours—yet showed no signs of decay. First-century witnesses would have immediately recognised this as miraculous.

- What about the burial spices—weren’t they meant to slow decomposition? The massive amount of spices Nicodemus brought (about 75 pounds, John 19:39) were primarily for honouring the dead, not preserving the body. Jewish burial customs didn’t involve embalming like Egyptian practices; the spices were aromatic substances meant to mask the smell of decomposition, not prevent it. Reformed exegete Matthew Henry notes these spices actually became evidence of the resurrection: the grave clothes remained with the spices intact (John 20:6-7), showing Jesus’s body passed through them. The body didn’t need the spices’ masking effect because it never began to smell of death.

Does this mean Christ’s body was somehow less human or less affected by death than ours? No—Reformed theology strongly affirms Christ’s full humanity. The Westminster Confession (8.2) insists He was “made of a woman, of the substance of her body” and possessed a true body. Herman Bavinck explained that Christ experienced death in its full horror—the separation of body and soul, the consequence of sin He bore for us. What was unique wasn’t His humanity or His death, but His person: the God-man whose sinless body had no internal principle of corruption. His body was as human as ours, but untouched by sin’s corruption because He was without sin.

- If Lazarus was raised, why did his body corrupt while Christ’s didn’t? This highlights the difference between resuscitation and resurrection. Lazarus was restored to his mortal, fallen body—the same body subject to sickness, aging, and eventually death again. John Owen observed that Lazarus’s body had already begun decomposing (hence Martha’s concern about the odour), and even after being raised, it remained a body still under the curse. Christ’s body, being sinless, had no intrinsic tendency toward corruption, and His resurrection transformed it into an immortal, glorified body. Lazarus went back to normal life; Christ entered glory.

- Did the Roman guards or Jewish authorities notice anything unusual about Christ’s body not decomposing? Scripture doesn’t explicitly tell us, but Reformed commentators note the irony: the authorities sealed the tomb and posted guards specifically to prevent the disciples from stealing the body (Matthew 27:62-66). Matthew Poole observes that by sealing the tomb, they inadvertently provided evidence that no human tampering occurred. When the tomb was found empty with the grave clothes undisturbed, the lack of decomposition during those three days became part of the evidence the apostles could cite. The guards’ own testimony that “something” happened (Matthew 28:11-15) suggests they encountered something beyond a simple missing corpse.

How does this truth connect to the Lord’s Supper? Reformed theology sees a profound connection. The bread represents Christ’s body—”given for you” (Luke 22:19), yet that same body saw no corruption and now lives forever. John Calvin taught that in the Supper we spiritually feed on Christ’s glorified, incorruptible body through faith by the Holy Spirit’s power. The body broken for us wasn’t conquered by death; it conquered death. When we take communion, we’re not remembering a defeated martyr but communing with our living, victorious Saviour whose incorruptible body guarantees our own resurrection bodies will be incorruptible too (1 Corinthians 15:42).

OUR RELATED POSTS

Editor's Pick

No Decay, No Defeat: What It Means That Christ’s Body Saw No Corruption

On the Day of Pentecost, Peter stood before thousands and made a startling claim: David's body decayed in the tomb, [...]

GPS Without Eyes: How Ants Silently Shout Intelligent Design

Picture a leafcutter ant navigating the rainforest floor in pitch darkness, carrying a leaf fragment 50 times its body weight. [...]

Does God Truly Care About My Everyday Choices?

We believe God created the universe. We believe He orchestrated the exodus from Egypt and raised Jesus from the dead. [...]

SUPPORT US:

Feel the Holy Spirit's gentle nudge to partner with us?

Donate Online:

Account Name: TRUTHS TO DIE FOR FOUNDATION

Account Number: 10243565459

Bank IFSC: IDFB0043391

Bank Name: IDFC FIRST BANK