If Sin’s Curse Is Broken, Why Does Childbirth Still Hurt?

The delivery room presents a puzzling contradiction. A Christian woman, justified by faith and adopted into God’s family, cries out in labour. She knows Christ declared “It is finished” on the cross. She believes Galatians 3:13—that Christ redeemed us from the curse of the law by becoming a curse for us. Yet here, in the intensity of childbirth, Genesis 3:16 feels devastatingly present: “I will surely multiply your pain in childbearing; in pain you shall bring forth children.”

If Christ has broken sin’s curse, why does this pain remain?

This isn’t merely an academic question. It touches every form of suffering Christians experience—disease, death, natural disasters, and yes, the intensified pain of bringing new life into the world. The Reformed tradition offers a robust answer, rooted not in evasion but in Scripture’s own “already/not yet” framework: Christ has indeed conquered the curse, but redemption unfolds according to God’s appointed timeline.

CHRIST’S VICTORY: REAL BUT NOT YET COMPLETE

When Christ cried “It is finished” from the cross, He accomplished something definitive. Galatians 3:13-14 is clear: Christ redeemed us from the curse by becoming a curse for us, so the blessing of Abraham might come to the Gentiles. Romans 8:1 thunders with finality: “There is therefore now no condemnation for those who are in Christ Jesus.” The curse’s primary reality—spiritual death, divine wrath, eternal separation from God—has been utterly vanquished.

But Calvin helps us with a crucial distinction. In his Institutes (2.16.5-6), he explains Christ bore the guilt and eternal penalty of the curse, but not every temporal consequence immediately. The curse’s sting is removed; its damnation is conquered. What remains are the temporal effects that serve God’s sanctifying purposes rather than His condemning judgement. The Westminster Confession (8.5) captures this precisely: Christ’s satisfaction ensured our final glorification, though we receive these benefits progressively.

Think of it this way: A prisoner pardoned by the king is truly free from execution, even if he doesn’t walk out of prison until the paperwork is processed. The legal reality precedes the experiential reality. Christ’s work guarantees our complete deliverance, but God applies this deliverance across time.

THE GROANING OF ROMANS 8: BETWEEN TWO AGES

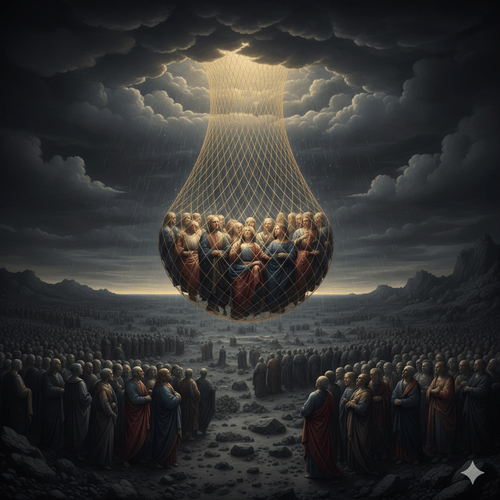

Romans 8:18-23 provides the theological architecture for understanding our current experience. Paul describes a three-fold groaning: creation groans (v. 22), believers groan (v. 23), and even the Spirit groans in intercession (v. 26). This groaning isn’t evidence that redemption failed—it’s proof that redemption is underway but incomplete.

Notice what Paul says: “The creation waits with eager longing for the revealing of the sons of God” (v. 19). All creation remains in “bondage to corruption” (v. 21), not because Christ’s work was insufficient, but because God has scheduled a day of final liberation. We who have “the firstfruits of the Spirit” still “groan inwardly as we wait eagerly for adoption as sons, the redemption of our bodies” (v. 23).

Herman Bavinck explains this in his Reformed Dogmatics (4:695-698). Childbirth pain, he explains, participates in creation’s groaning—the labour pangs of a world being reborn. The pain isn’t punishment; it’s the birth canal through which new creation emerges. Just as a woman’s labour pain is intense but temporary, pointing forward to the joy of new life (John 16:21), so all of creation’s groaning points toward the glory to be revealed.

Francis Turretin adds precision: In his Institutes of Elenctic Theology (Topic 15, Q. 13), he distinguishes between Christ securing the right to complete redemption and the Holy Spirit applying that redemption progressively. Christ’s work on the cross purchased our full salvation—body and soul, physical and spiritual. But God applies this salvation in stages: justification at conversion, sanctification throughout life, glorification at the resurrection.

The “already” blessings are glorious: we have peace with God, the Spirit’s indwelling, assurance of salvation, and victory over sin’s dominion. The “not yet” awaits Christ’s return: physical resurrection, glorified bodies, renewed creation, and death’s final destruction (1 Corinthians 15:25-26).

WHY THE WAIT? GOD’S SANCTIFYING PURPOSES

If God could remove all suffering now, why doesn’t He? The Reformed tradition offers several biblical answers, all refusing to minimise either God’s sovereignty or the reality of pain.

- First, temporal sufferings serve as sanctifying instruments. John Owen, in The Death of Death in the Death of Christ, explains Christ’s death secured not just our forgiveness but our transformation. God uses present suffering—including childbirth pain—to wean us from this world and intensify our longing for the next. Paul says it plainly: “This light momentary affliction is preparing for us an eternal weight of glory beyond all comparison” (2 Corinthians 4:17).

- Second, our groaning keeps us in solidarity with all creation.We’re not Gnostics who despise the physical world and seek escape from bodily existence. We’re Christians who affirm that creation itself will be liberated (Romans 8:21). Our physical sufferings remind us redemption isn’t just about souls going to heaven—it’s about heaven coming to earth, bodies being raised, and creation being renewed.

- Third, remaining consequences preview our deepening longing for Christ’s return. Louis Berkhof notes in his Systematic Theology (p. 547) that if we experienced full glorification now, we might lose our eager expectation of Christ’s appearing. Every pain, every groan, every difficulty whispers, “This world is not your home.” The Heidelberg Catechism (Q&A 32) reminds us we’re called Christians precisely because we share in Christ’s anointing—which includes sharing His sufferings now and His glory later.

Childbirth pain, then, is neither divine punishment nor a cosmic accident. It’s an eschatological sign—a reminder that we live between Eden and the New Jerusalem, between the cross and the crown, between resurrection and return.

LIVING WITH HOPE BETWEEN TWO GARDENS

So what do we say to the woman in labour, or to anyone enduring suffering in this fallen world?

- Our pain isn’t condemnation. The curse’s judgement is removed, even though its remnants remain. We aren’t experiencing God’s wrath but His fatherly discipline and preparation for glory.

- Our groaning is eschatological hope. Like birth pangs, our present suffering is temporary, purposeful, and productive. It announces something better is coming. The Westminster Shorter Catechism (Q. 38) promises that believers receive manifold benefits both in this life and after death—culminating in the resurrection when we’re “made perfectly blessed in the full enjoying of God to all eternity.”

- Our Saviour guarantees our complete deliverance. Hebrews 2:8-9 acknowledges the tension honestly: “At present, we do not yet see everything in subjection to him. But we see Jesus.” Our full redemption is as certain as Christ’s resurrection. The same power that raised Him will raise us (Romans 8:11).

The curse is broken—its condemnation vanquished, its eternal power destroyed, its ultimate victory cancelled. But like dawn breaking before the sun fully rises, redemption’s light shines while shadows remain. Every pain is a birth pang. Every groan echoes resurrection hope. And one day soon, the curse will be fully and finally removed: “No longer will there be anything accursed” (Revelation 22:3).

Until that day, we labour—in childbirth, in life, in faith—with a hope that does not disappoint, knowing our redemption draws near.

RELATED FAQs

Do we view childbirth pain as purely punitive or do we see any positive purpose in it? Reformed theology rejects a purely punitive view of childbirth pain for believers. Calvin argued in his commentary on Genesis 3:16 that while the pain originates from the fall, God transforms it for believers into a sanctifying discipline rather than condemnation. Matthew Henry famously noted that childbirth pain, though genuinely difficult, is followed by joy and produces “the fruit of the womb,” making it distinct from purely penal suffering. Bavinck emphasised labour becomes a participation in the “groaning” of Romans 8—not punishment but the birth pangs of new creation, productive and hope-filled, rather than merely retributive.

- How have Christian women themselves reflected on childbirth pain and Genesis 3:16? Reformed women like Anne Bradstreet (17th century Puritan poet) wrote movingly about childbirth as both a sobering reminder of the fall and an occasion for deepened trust in God’s sovereignty. Susanna Wesley, mother of John and Charles Wesley and steeped in Reformed theology, viewed her difficult labours as opportunities for spiritual growth and dependence on divine grace. Contemporary Reformed theologian Kathleen Nielson writes childbirth pain uniquely positions women to understand groaning, hope, and new creation in visceral ways, making Genesis 3:16 not just about curse but about women’s distinctive participation in redemptive history. These women refused to see themselves as merely victims of the curse, instead finding theological meaning and spiritual purpose in their experience.

- If animals also experience pain in reproduction, doesn’t that suggest Genesis 3:16 isn’t really about sin’s curse? This objection actually strengthens the Reformed position rather than weakening it. Romans 8:20-22 explicitly states “the creation was subjected to futility” and that “the whole creation has been groaning together in the pains of childbirth.” The fall didn’t just affect humanity—it corrupted all of creation, including animal reproduction. Genesis 3:17 curses the ground itself, indicating cosmic consequences beyond human experience alone. What’s distinctive about Genesis 3:16 is the multiplication or intensification of pain specifically for human women, not the introduction of pain into a previously painless process. Turretin and other Reformed theologians saw animal suffering as evidence of how deeply sin corrupted God’s “very good” creation, making redemption necessarily cosmic in scope.

Does the “already/not yet” framework mean Christians should never seek pain relief during childbirth? Absolutely not—this would be a serious misapplication of Reformed theology. The same logic that allows Christians to use medicine for disease, surgery for injury, or glasses for poor eyesight applies to childbirth pain relief. Calvin himself argued that using God’s gifts of medical knowledge honours the Creator who gave us dominion over creation and the intellect to develop remedies. The “already/not yet” framework explains why pain exists in a redeemed world, not whether we should alleviate it when possible. Just as we don’t refuse chemotherapy because cancer exists in a fallen world, we shouldn’t refuse epidurals because childbirth pain stems from Genesis 3:16. God’s common grace includes medical advances that ameliorate the effects of the fall without removing the underlying eschatological tension.

- How does the Reformed view differ from Roman Catholic perspectives on childbirth pain and redemptive suffering? While both traditions take Genesis 3:16 seriously, they differ significantly in application. Roman Catholic theology, especially influenced by Pope John Paul II’s “Theology of the Body,” often emphasises childbirth pain as uniquely redemptive suffering that can be “offered up” for spiritual merit. The Reformed tradition firmly rejects any notion that human suffering contributes merit toward salvation—Christ’s work alone is sufficient. Reformed theology views childbirth pain as sanctifying (making us more Christlike) rather than redemptive (contributing to salvation). Westminster Confession 11.2 explicitly denies that our suffering adds anything to Christ’s complete atonement. This difference reflects the broader Reformation principle of sola gratia—grace alone, with no human contribution to redemption itself.

- What about Genesis 3:16’s phrase “multiply” or “greatly increase”—does this mean there was some pain before the fall? This is a fascinating exegetical question that Reformed scholars have debated. Some, like Francis Turretin, argued “multiply” suggests intensification of an existing experience rather than introduction of something entirely new—though he maintained this was speculation beyond Scripture’s explicit statement. Others, like Geerhardus Vos, suggested the language may be idiomatic Hebrew emphasis rather than mathematical multiplication. Most Reformed commentators focus on what’s clear: after the fall, childbirth pain became substantially greater and served as a perpetual reminder of sin’s consequences.

If someone experiences relatively easy childbirth, does that mean they’re somehow less affected by the curse? Not at all—this misunderstands both the nature of the curse and God’s providential distribution of suffering. Reformed theology has always recognised enormous variation in how individuals experience fallen-world consequences: some die young, others live to 100; some battle chronic illness, others enjoy robust health. Childbirth difficulty varies widely due to countless factors including genetics, medical care, individual physiology, and God’s inscrutable providence. The curse of Genesis 3:16 describes a general reality for humanity—that childbirth involves pain in a way it wouldn’t have in an unfallen world—not a uniform experience for every woman. Berkhof reminds us that God distributes temporal blessings and difficulties according to His wise purposes, not according to individual merit or curse-worthiness. An easy labour is simply evidence of God’s common grace, not an exemption from the fall’s effects.

OUR RELATED POSTS

Editor's Pick

Why Do People Hate the Doctrine of Election?

…WHEN THEY REALLY SHOULDN’T Few Bible doctrines provoke stronger reactions than election. The idea that God chose some for salvation [...]

The Doctrine of Providence: Does God Really Govern All Things?

You’re sitting in the doctor’s office when the diagnosis lands like a thunderclap. Your mind races: Why this? Why now? [...]

No Decay, No Defeat: What It Means That Christ’s Body Saw No Corruption

On the Day of Pentecost, Peter stood before thousands and made a startling claim: David's body decayed in the tomb, [...]

SUPPORT US:

Feel the Holy Spirit's gentle nudge to partner with us?

Donate Online:

Account Name: TRUTHS TO DIE FOR FOUNDATION

Account Number: 10243565459

Bank IFSC: IDFB0043391

Bank Name: IDFC FIRST BANK