What Does Sheol Mean? Hell, Grave, Or Something Else?

You’re reading along in the Old Testament and suddenly the word Sheol jumps off the page. One translation calls it “hell,” another says “the grave,” and yet another just leaves it as “Sheol.” You pause and wonder: Where exactly did folks back then think they were going when they died? Was it a fiery torture chamber? A cold, silent tomb, perhaps? A halfway house for souls? Did the heroes of the faith—Abraham, Moses, David himself—linger in some gloomy waiting room until Jesus showed up? The confusion is real, and it matters, because what the Bible says about Sheol shapes how we face death, grieve our loved ones, and cling to the hope of the gospel.

THE OLD TESTAMENT PICTURE: A REALM SHROUDED IN MYSTERY

In the Hebrew Scriptures, sheol appears more than 65 times. It consistently refers to the realm of the dead—the unseen place where all who die initially go. Job describes it as the great equaliser where “the small and the great are there, and the slave is free from his master” (Job 3:19). The Preacher notes that in sheol “there is no work or thought or knowledge or wisdom” (Ecclesiastes 9:10).

This presents an immediate puzzle: Even the righteous descend to sheol. Jacob mourns he will go down to sheol after his son Joseph (Genesis 37:35). The psalmist cries out from sheol’s depths (Psalm 88:3). Yet we know God’s people don’t suffer the same fate as the wicked. What’s going on?

John Calvin observed sheol primarily denotes the state of death itself—the departure from this visible world into the unseen realm beyond. It’s described as “beneath” (Numbers 16:30), a place of darkness and silence (Psalm 88:12), cut off from earthly activity. But Calvin recognised this wasn’t the full story. The term carries eschatological weight that only later revelation would unpack.

Francis Turretin sharpened the point: sheol represents the general condition of death, but within that state, the experiences of the righteous and wicked differ profoundly—something the Old Testament hints at but doesn’t fully elaborate.

FROM SHADOW TO SUBSTANCE: PROGRESSIVE REVELATION AT WORK

Here’s where the principle of progressive revelation becomes essential. God didn’t download complete systematic theology to Moses. He taught his people gradually, as a father instructs children, moving from foundational truths to fuller clarity.

The Old Testament itself shows this development. Psalm 49:15 marks a turning point: “But God will ransom my soul from the power of Sheol, for he will receive me.” The psalmist knows sheol isn’t his final destination. Isaiah 38:18 notes “Sheol does not thank you; death does not praise you”—implying the righteous go somewhere that does allow praise. By Daniel 12:2, we have explicit teaching: “Many of those who sleep in the dust of the earth shall awake, some to everlasting life, and some to shame and everlasting contempt.”

Even the ancient Greek translators noticed sheol’s semantic range. Sometimes they rendered it hades (the underworld), sometimes thanatos (death), sometimes mnemeion (grave). They recognised it wasn’t a precise technical term but a placeholder for the complex reality of death.

Louis Berkhof explained that Old Testament saints possessed a “dimmer consciousness” of afterlife distinctions—not because Scripture was false, but because fuller revelation was still awaited. The Westminster Confession crystallises the mature understanding: “The bodies of men, after death, return to dust… but their souls… return to God… The souls of the righteous… are received into the highest heavens… the souls of the wicked are cast into hell” (32.1).

GK Beale’s canonical approach helps us read this rightly: The Old Testament’s sheol language prepares God’s people for the New Testament’s clearer distinction between heaven and hell. It’s not contradiction but careful pedagogy.

CHRIST BRINGS CLARITY

Jesus divides what the Old Testament left ambiguous. In Luke 16, Hades (Greek for sheol) contains both Abraham’s side, where Lazarus rests in comfort, and the place of torment, where the rich man suffers consciously. They’re separated by an unbridgeable chasm, yet both are “in Hades.”

Paul removes all doubt: to be “away from the body” is to be “at home with the Lord” (2 Corinthians 5:8). When Jesus tells the repentant thief, “Today you will be with me in paradise” (Luke 23:43), he’s not describing soul sleep or some neutral waiting room. It’s immediate, conscious, blessed fellowship.

William GT Shedd’s insight proves valuable: these distinctions were always real. God simply revealed them gradually, protecting his people from knowledge they weren’t yet ready to process while ensuring they trusted him with their eternal destiny.

WHY THIS MATTERS NOW

Understanding sheol isn’t academic hairsplitting. It shapes how we read a third of our Bible. When we see “sheol” in the Old Testament, we recognise it as the language of death’s mystery—a mystery Christ has now unveiled.

It gives us confidence at funerals. When believers die, they’re not in some shadowy waiting room. They’re genuinely, consciously, joyfully with Christ. No purgatory. No soul sleep. Present with the Lord.

It also keeps us humble about progressive revelation. God’s people in every age had sufficient truth for their time. We’re privileged to stand on this side of the empty tomb, where shadows have given way to substance.

FROM MYSTERY TO CERTAINTY

Sheol isn’t the final word; Jesus is. He entered the realm of the dead, shattered its gates, and brought His people out forever. The moment a believer breathes his or her last today, there is no shadowy Sheol, no anxious delay—only the immediate, unspeakable joy of being “with Christ, which is far better.” Death has been swallowed up in victory. Because our Forerunner has gone ahead and cleared the way, we do not descend into the shadows. We’re carried straight into the light of His face.

For the believer, the mystery of sheol has become the certainty of paradise.

RELATED FAQs

Did Old Testament believers go to heaven when they died? Yes, but the Old Testament doesn’t explicitly use “heaven” language for their destination. Reformed scholars like Michael Horton emphasise the redeemed of all ages share the same salvation through Christ, even if Old Testament saints experienced it through types and shadows. They trusted God’s promises and were received into his presence, though they lacked the full clarity believers now possess post-resurrection. The substance was always the same; only the revelation differed.

- What does the Apostles’ Creed mean by “he descended into hell”? The Westminster Larger Catechism (Q. 50) interprets this as Christ’s humiliation in death—his soul experiencing the state of the dead and his body remaining in the tomb. Reformed theologian Robert Letham clarifies this wasn’t a descent into torment or a “harrowing of hell” as medieval theology suggested, but Christ’s genuine experience of death’s full reality. John Calvin argued the phrase primarily refers to Christ’s suffering of God’s wrath on the cross, not a literal journey to sheol after death.

- How does sheol relate to Gehenna in the New Testament? They’re distinct concepts. Sheol/Hades refers to the intermediate state of the dead, while Gehenna describes the lake of fire—the final, eternal judgement after resurrection—what we typically call “hell proper.” Contemporary Reformed scholar Robert Peterson notes Gehenna (derived from the Valley of Hinnom) always refers to post-judgement punishment in Jesus’ teaching. The Westminster Confession’s distinction between the intermediate state (32.1) and final judgement (33.1-2) captures this biblical progression from sheol/hades to the lake of fire.

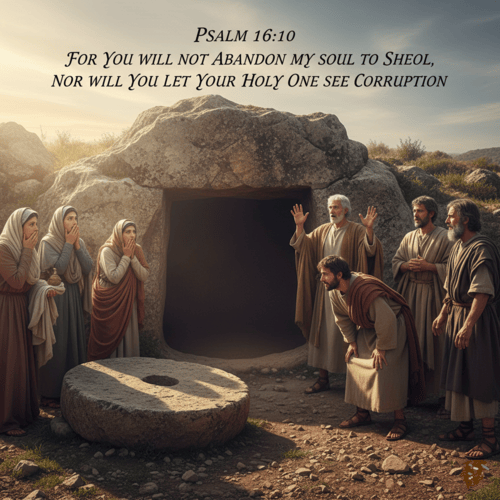

Why do some Psalms seem to deny afterlife hope if sheol isn’t just the grave? Psalms like 6:5 (“in death there is no remembrance of you; in Sheol who will give you praise?”) reflect earthly perspective and the limitations of pre-resurrection revelation. Vern Poythress explains these passages emphasise that death ends our earthly service and witness, not that consciousness ceases. They’re written from the vantage point of those left behind, lamenting the loss of visible fellowship and service. The psalmists knew God’s steadfast love extended beyond death (Psalm 16:10-11) even when they couldn’t articulate the mechanics.

- Do Reformed theologians believe in “soul sleep” between death and resurrection? No, classical Reformed theology consistently rejects soul sleep (the idea that souls are unconscious until resurrection). The Westminster Confession explicitly states souls are “received” or “cast” to their destinations immediately at death. Contemporary scholars like Sinclair Ferguson and JI Packer affirm conscious intermediate existence based on passages like Luke 16:19-31, Philippians 1:23, and Revelation 6:9-11. The Reformers opposed both the Anabaptist teaching of soul sleep and the Catholic doctrine of purgatory, charting a middle path of immediate, conscious destination.

- How do we explain passages where God “brings up from Sheol” (1 Samuel 2:6)? These passages use sheol figuratively for extreme danger, life-threatening illness, or deliverance from near-death experiences. Derek Kidner and other Old Testament scholars note this poetic usage emphasises God’s sovereignty over life and death without requiring literal trips to the realm of the dead. It’s similar to how we might say someone was “at death’s door”—acknowledging proximity to death without claiming they actually died. This figurative use appears frequently in Psalms and wisdom literature.

What about 1 Peter 3:19-20 and Christ preaching to “spirits in prison”? This notoriously difficult passage has generated multiple Reformed interpretations. Wayne Grudem argues it refers to Christ’s pre-incarnate proclamation through Noah to disobedient people (now dead spirits). DA Carson suggests it describes Christ’s post-resurrection proclamation of victory over fallen angels. Herman Bavinck viewed it as Christ’s announcement of triumph to imprisoned demonic powers. Most Reformed scholars agree it doesn’t support a “second chance” after death or purgatory, whatever the precise meaning. The passage’s obscurity means we shouldn’t build doctrine on it alone.

OUR RELATED POSTS

Editor's Pick

Why Do People Hate the Doctrine of Election?

…WHEN THEY REALLY SHOULDN’T Few Bible doctrines provoke stronger reactions than election. The idea that God chose some for salvation [...]

The Doctrine of Providence: Does God Really Govern All Things?

You’re sitting in the doctor’s office when the diagnosis lands like a thunderclap. Your mind races: Why this? Why now? [...]

No Decay, No Defeat: What It Means That Christ’s Body Saw No Corruption

On the Day of Pentecost, Peter stood before thousands and made a startling claim: David's body decayed in the tomb, [...]

SUPPORT US:

Feel the Holy Spirit's gentle nudge to partner with us?

Donate Online:

Account Name: TRUTHS TO DIE FOR FOUNDATION

Account Number: 10243565459

Bank IFSC: IDFB0043391

Bank Name: IDFC FIRST BANK