Can a Believer’s Children Be Among the Non-Elect?

Every Reformed parent has felt the weight of this question. Watching a sleeping child, we’ve wondered: “Is my baby among God’s elect?”

See how Scripture’s answer is simultaneously sobering and comforting. Yes, a believer’s children can be among the non-elect—but this biblical truth doesn’t contradict God’s precious covenant promises to believing families. Understanding the distinction between covenant membership and election is essential for both theological clarity and pastoral peace.

THE BIBLICAL REALITY: NOT ALL IN THE COVENANT ARE ELECT

Scripture speaks with unflinching clarity: being born into a believing family doesn’t guarantee election. The apostle Paul states this principle explicitly in Romans 9:6-8: “Not all who are descended from Israel are Israel. Nor because they are his descendants are they all Abraham’s children.” Physical descent from Abraham didn’t ensure spiritual inheritance. Being in the covenant community and being eternally elect are not identical categories.

Consider the sobering biblical examples.

- Jacob and Esau were both sons of Isaac and Rebekah, both circumcised on the eighth day, both raised in a godly home. Yet before they were born, God chose Jacob and passed over Esau (Romans 9:11-13).

- Ishmael was Abraham’s son, bore the covenant sign of circumcision, yet was not the child of promise (Genesis 17:18-21).

- In Israel’s history, countless covenant members received every external privilege—circumcision, the law, the temple, the sacrifices—yet perished in unbelief.

- The writer of Hebrews warns of those who profane “the blood of the covenant by which he was sanctified” (Hebrews 10:29), acknowledging that covenant members can apostatise.

- 1 John 2:19 describes those who “went out from us, but they did not really belong to us.”

This biblical pattern forces us to distinguish between two aspects of God’s covenant: the historical administration (which includes believers and their children) and the eternal reality (which includes only the elect). This isn’t a theological trick to avoid difficulty; it’s what Scripture itself teaches.

THE WESTMINSTER STANDARDS: COVENANT AND ELECTION DISTINGUISHED

The Westminster Confession of Faith carefully maintains this biblical distinction. The Confession states God’s covenant of grace is made “with Christ as the second Adam, and in him with all the elect” (WCF 7.3). Yet it also states the visible church consists “of all those throughout the world that profess the true religion, together with their children” (WCF 25.2). Notice the careful language: covenant membership extends to believers and their children, but the covenant’s saving benefits belong definitively to the elect alone.

This dual aspect appears most clearly in the Confession’s teaching on baptism. Westminster explicitly states “all that are baptised are not undoubtedly regenerated” (WCF 28.5). The sacrament is rightly administered to covenant children, yet the grace signified is not automatically conferred. Baptism marks covenant inclusion, not unconditional election.

The Canons of Dort similarly affirm children of believers are “holy, not by nature but by virtue of the covenant of grace” (I.17). They state elect infants dying in infancy are certainly saved, but carefully avoiding the claim that all covenant children are necessarily elect.

THE HISTORIC REFORMED POSITION: A CHARITABLE PRESUMPTION

Here’s where pastoral wisdom meets theological precision. While Reformed theology has consistently affirmed that not all covenant children are elect, it has equally emphasised what we might call a “judgement of charity” toward our children. Historically, Reformed theologians like Calvin, Bavinck, Warfield, and others have explicitly taught a charitable presumption of regeneration in covenant children unless evidence firmly contradicts it.

Historic Reformed theology taught covenant children are to be regarded as elect and regenerate, until the opposite is apparent from their profession and behaviour. This represented the mainstream position among Reformed divines including Ursinus, Voetius and Witsius. Calvin wrote the children of believers are holy even before baptism through a supernatural work of grace, with the seed of faith hidden within them through the Spirit’s secret operation.

BB Warfield argued “all baptism is inevitably administered on the basis not of knowledge but of presumption,” and that we should baptise all whom we may fairly presume to be members of Christ’s body. This isn’t naïve optimism—it’s covenant theology rightly applied. We don’t claim infallible knowledge of our children’s regeneration, but we treat them according to God’s promise: “The promise is for you and your children” (Acts 2:39).

This judgement of charity means we raise our children as Christians, instructing them in the faith, expecting them to participate in worship, teaching them to pray—all while knowing only those whom God has chosen will persevere. We presume regeneration not because all covenant children are automatically elect, but because God has made His covenant with believers and their offspring, and we honor that covenant commitment.

PASTORAL COMFORT: WHAT THIS MEANS FOR CHRISTIAN PARENTS

So what should Reformed parents do with this doctrine?

- We rest in God’s promise. Genesis 17:7 declares, “I will establish my covenant as an everlasting covenant between me and you and your descendants after you.” This promise is real, not empty. Our children stand in a different relationship to God than the children of unbelievers. They are set apart, claimed by God, and placed under the ministry of His Word and Spirit.

- We faithfully discharge our covenant responsibilities. Ephesians 6:4 commands us to bring up our children “in the training and instruction of the Lord.” We baptise them in faith, trusting God’s covenant faithfulness. We teach them Scripture, pray with them, model godliness before them, and discipline them lovingly. We practice family worship not because it mechanically produces regeneration, but because these are the means God has appointed for transmitting faith to the next generation.

- We pray fervently while resting in God’s sovereignty. The doctrine of election doesn’t discourage prayer; it directs it. We pray because God works through means, and parental intercession is a powerful means. We pray knowing that if our children are elect, God will certainly bring them to faith, and our prayers are part of how He accomplishes His purposes.

- We avoid two deadly errors. We reject presumption—the false assumption that all baptised children are automatically saved regardless of their life and profession. But we equally reject despair—the anxious conclusion that our covenant standing means nothing and that our children are no different than pagans’ children. Both errors dishonour God’s covenant.

THE HEART OF THE MATTER: TRUST AND RESPONSIBILITY

Can a believer’s children be among the non-elect? Yes—Scripture and church history answer clearly. Jacob’s family included Esau. Abraham’s household included Ishmael. The disciples’ circle included Judas. Yet this sobering reality doesn’t nullify God’s gracious promise. It clarifies what the promise means.

The doctrine of election, rightly understood, should drive us as Reformed parents to our knees in prayer and to diligence in godly parenting, never to presumption or passivity. We entrust our children to the God who chose us, knowing He is faithful to His covenant. We raise them as believers, expecting God to confirm His promise in their lives, while acknowledging the final verdict belongs to Him alone.

In the end, this doctrine magnifies grace. If all covenant children were automatically elect, their salvation would depend partly on their birth. But salvation belongs to the Lord—for our children as for us. And that is precisely where our confidence rests: not in our faithfulness as parents, nor in our children’s covenant status, but in the God who is “faithful to all his promises and loving toward all he has made” (Psalm 145:13). He has given us His covenant word: “The promise is for you and your children.” That is enough.

RELATED FAQs

Does Reformed theology teach “presumptive regeneration” for covenant children? Historically, yes—this was the mainstream Reformed position. Calvin, Bavinck, Warfield, and Dabney all taught that covenant children should be presumed regenerate unless evidence contradicts it. Herman Bavinck wrote covenant children “are to be regarded as elect and regenerate, until the opposite is apparent from their profession and behaviour.” This wasn’t naïve presumption but covenant faithfulness—treating God’s promises to believing parents (Genesis 17:7, Acts 2:39) as real and operative. Modern Reformed churches vary: some maintain this charitable judgement, while others take a more cautious “wait and see” approach that treats baptised children as merely in the visible church’s sphere.

- How does the Reformed Baptist position differ from the Presbyterian view on this question? Reformed Baptists resolve the covenant-election tension differently: they practice believer’s baptism only, arguing that the New Covenant includes only the regenerate (citing Jeremiah 31:31-34). For them, children of believers aren’t “in covenant” until they profess faith, so the question of non-elect covenant children doesn’t arise in the same way. Presbyterians and Reformed paedobaptists maintain God establishes His covenant with believers and their children (Genesis 17:7), meaning covenant membership is broader than election. Both affirm that only the elect are finally saved, but they disagree on who receives the covenant sign. The debate ultimately centres on covenant continuity: do New Covenant administration principles mirror Old Covenant practices (infant inclusion) or represent a decisive break (believers only)?

- What do modern Reformed scholars teach about election and covenant? DA Carson emphasises election is unconditional and sovereignly determined by God, independent of human merit or foreseen faith. In his commentary on John’s Gospel, Carson argues faith itself flows from sovereign election (John 6:37-44), though he maintains human responsibility for belief remains real. John Piper, as a Reformed Baptist, teaches election as the foundation of salvation but doesn’t practice infant baptism, avoiding the Presbyterian tension between covenant membership and election. Both scholars stress election should drive believers to prayer and faithful parenting rather than presumption or despair. Their work represents the “New Calvinist” movement’s emphasis on God’s sovereignty while maintaining evangelistic urgency—the elect will certainly believe, but we don’t know who they are, so we preach, teach, and parent as if all could be saved.

Doesn’t treating non-elect people as covenant members make baptism meaningless? No—it recognises Scripture’s own distinction between covenant administration and eternal reality. In the Old Testament, Ishmael and Esau received circumcision despite not being children of promise. Israel itself was God’s covenant people, yet Romans 9:6 teaches “not all who are descended from Israel are Israel.” The covenant sign marks membership in the visible covenant community and signifies God’s promises, but it doesn’t automatically confer the grace it represents—that belongs to the elect through faith. As Westminster Confession 28.5 states, “all that are baptised are not undoubtedly regenerated.” Baptism has profound meaning: it marks covenant privilege, God’s promise, parental obligation, and the means by which God typically works. But like Israel’s circumcision, the external sign doesn’t guarantee internal transformation. This isn’t baptism’s failure; it’s acknowledging that God’s secret will (election) differs from His revealed will (covenant promises).

- If my child apostatises, does that mean God’s covenant promise failed? No—it means your child was in the historical administration of the covenant but not among the elect. God’s covenant promise was never “every baptised child is automatically elect.” Rather, God promises to work among covenant families through the means of grace—Word, sacraments, prayer, discipline. When covenant children persevere in faith, the promise is confirmed; when they apostatise, they prove they were never truly “of us” (1 John 2:19). Think of Hebrews 10:29, which speaks of those who “profaned the blood of the covenant by which he was sanctified”—covenant language applied to apostates. Your faithful covenant nurture wasn’t wasted; it was your God-given duty. God’s saving of the elect never depended on perfect parenting, and the apostate’s damnation isn’t due to your parental failure. Election is God’s sovereign work; covenant faithfulness is your responsibility. The promise remains trustworthy even when some covenant members fall away.

- How should this doctrine affect how I raise my children day-to-day? We raise them as Christians while acknowledging only God knows their eternal state. This means: (1) Baptising them in faith, trusting God’s covenant promise. (2) Teaching them the Scriptures as disciples, not merely moral instructions as outsiders. (3) Praying with them and for them fervently, knowing God works through means. (4) Practicing family worship, expecting the Spirit to work through His Word. (5) Disciplining them within the covenant context, calling them to repentance as covenant children, not treating them as pagans. (6) Exercising the “judgement of charity”—presuming they’re regenerate while watching for fruit. (7) Calling them to examine themselves and ensure their profession is genuine, especially as they mature. This isn’t contradictory; it’s biblical realism. We don’t treat our children as pagans needing conversion alone, nor as automatically saved needing no personal faith. We nurture covenant faith while trusting God for regeneration.

Why does God allow elect parents to have non-elect children? Doesn’t this seem cruel? This question wrestles with God’s sovereignty, which applies to all election—why does God save anyone? The more specific question assumes children of believers somehow deserve election more than others, but Scripture denies this (Romans 9:11-13). Jacob and Esau were twins with identical covenant privileges, yet God chose differently before birth. God’s election is always unconditional and according to His own purposes. The doctrine’s difficulty shouldn’t surprise us—salvation is “of the Lord” (Jonah 2:9), not of human will or descent (John 1:13). What’s remarkable is God’s grace in establishing covenants with families at all, providing means of grace, and typically working salvation through covenant lines (Acts 2:39). We have more reason to rejoice that God includes covenant children in His redemptive administration than to complain that not all are elect. The alternative—every child automatically saved by parental faith—would make salvation partly of human descent, contradicting grace’s very nature. This doctrine magnifies grace precisely because it shows salvation resting entirely in God’s sovereign mercy, not in our bloodlines.

OUR RELATED POSTS

Editor's Pick

Christian Obedience: God’s Empowerment or an Act of Our Will?

Every Christian knows the struggle. You’re fighting a besetting sin—again. You’ve resolved to do better—again. And you’re wondering: Should I [...]

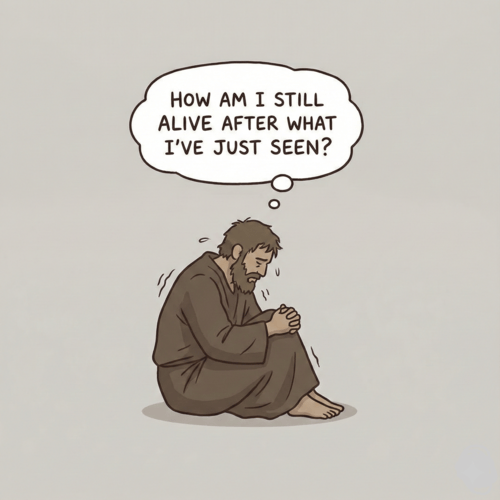

The Throne-Room Vision: Who Did Isaiah See?

The scene is unforgettable: Isaiah stands in the temple, and suddenly the veil between heaven and earth tears open. He [...]

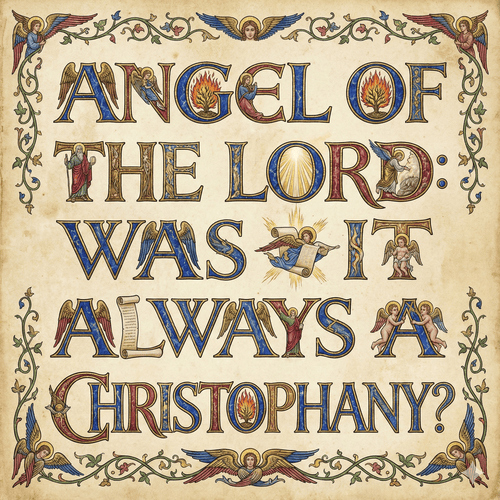

The Angel of the Lord: Can We Be Certain It Was Christ All Along?

Throughout the Old Testament, a mysterious figure appears: the Angel of the LORD. He speaks as God, bears God’s name, [...]

SUPPORT US:

Feel the Holy Spirit's gentle nudge to partner with us?

Donate Online:

Account Name: TRUTHS TO DIE FOR FOUNDATION

Account Number: 10243565459

Bank IFSC: IDFB0043391

Bank Name: IDFC FIRST BANK