Can I Doubt Bible Inerrancy and Still Be a Christian?

If we’ve struggled with this question, let’s take heart: we aren’t alone. Sincere believers often wrestle with Scripture’s authority while genuinely loving Jesus. Perhaps we’ve encountered historical difficulties in the biblical text, or scientific questions that seem hard to reconcile with Genesis. Or maybe we’re just honest enough to admit that some passages are downright puzzling. The good news? Asking hard questions doesn’t disqualify us from the kingdom. The question, nevertheless, does deserve a thoughtful, biblical answer.

WHAT INERRANCY ACTUALLY MEANS

Before we answer whether we can doubt inerrancy and still be Christian, we need clarity on what inerrancy actually claims. The doctrine insists Scripture is truthful and without error in everything it affirms. As Paul declares: “All Scripture is breathed out by God and profitable for teaching, for reproof, for correction, and for training in righteousness” (2 Timothy 3:16).

But here’s what inerrancy doesn’t mean: It’s not claiming the Bible uses modern scientific precision, provides exhaustive detail on every subject, or writes history like a 21st century academic journal. The Reformed tradition recognises God accommodates human language, culture, and literary genres without compromising truth. When Jesus says he is “the door” (John 10:9), we understand metaphor. When the Psalms describe the “four corners of the earth” (Psalm 48:2), we recognise ancient Near Eastern cosmological language.

The Chicago Statement on Biblical Inerrancy wisely distinguishes between what Scripture affirms and incidental details of human expression. Scripture is inerrant in its original manuscripts regarding everything it intends to teach—whether theological, historical, or moral.

The crucial Reformed principle is this: Scripture functions as the norma normans—the “norming norm.” It’s the final standard by which all other truth claims are measured. This authority, more than technical inerrancy, is what the Reformation recovered.

CAN I BE CHRISTIAN WHILE QUESTIONING INERRANCY?

Here’s the clear Reformed answer: Yes, but with important qualifications.

Justification is by faith in Christ alone, not by doctrinal perfection. Paul is emphatic: “For by grace you have been saved through faith. And this is not your own doing; it is the gift of God, not a result of works” (Ephesians 2:8-9). Salvation requires confessing “Jesus is Lord” and believing “that God raised him from the dead” (Romans 10:9). Nowhere does Scripture add: “and you must hold a fully developed doctrine of biblical inerrancy.”

Throughout church history, believers have grown into fuller understanding. Even the disciples doubted and questioned before their faith matured. God is remarkably patient with honest seekers.

However—and this is crucial—doubting inerrancy creates serious theological tensions you cannot ignore. If Scripture errs in its historical claims, why should we trust its theological claims? The foundation becomes unstable. Jesus himself affirmed Scripture’s authority extensively, declaring, “Scripture cannot be broken” (John 10:35), and insisting that not “an iota, not a dot” would pass from the Law until all is accomplished (Matthew 5:18). The apostles grounded their arguments in Scripture’s complete reliability. Peter wrote that “no prophecy was ever produced by the will of man, but men spoke from God as they were carried along by the Holy Spirit” (2 Peter 1:20-21).

John Calvin taught Scripture is self-authenticating through the Holy Spirit’s internal testimony. We don’t believe Scripture is God’s Word because scholars prove it—we believe because the Holy Spirit witnesses to our hearts. Herman Bavinck helpfully explained that inspiration is “organic”—God works through human personalities, cultures, and styles without compromising divine truthfulness.

The trajectory of our hearts matters immensely. Are we moving toward submission to Scripture or away from it? Are we wrestling to understand, or rationalising disobedience? God honours the former; He warns against the latter.

BUT IS FAITH IN INERRANCY ESSENTIAL FOR SALVATION?

Let’s be direct: No, affirming inerrancy isn’t essential for salvation. Salvation requires faith in Christ, not a particular doctrine about Scripture. Genuine believers have been known to hold developing or nuanced views on biblical authority.

But here’s the tension: While you can be saved without affirming inerrancy, you cannot be saved while completely denying Scripture’s authority. Why? Because how do we know about Christ except through Scripture? “Faith comes from hearing, and hearing through the word of Christ” (Romans 10:17). The gospel message itself rests on Scripture’s testimony. If Scripture is fundamentally unreliable, we have no gospel.

In the Reformed tradition, we distinguish between primary and secondary doctrines. The deity of Christ, His atoning death, and bodily resurrection are primary—deny these and you’ve abandoned Christianity. Inerrancy is “ministerial”—it serves and protects the gospel. The Westminster Confession calls Scripture “the only infallible rule of faith and practice,” recognising that biblical authority undergirds everything else.

History, however, offers a sobering warning: Erosion of biblical authority consistently leads to theological drift. Churches that began questioning Scripture’s reliability eventually questioned Christ’s uniqueness, the reality of sin, and the necessity of the cross.

Yet Scripture itself gives us hope for doubters. When the desperate father cried, “I believe; help my unbelief!” (Mark 9:24), Jesus didn’t reject him—He healed his son. God is patient with honest questions.

LIVING IN THE TENSION

If you’re wrestling with inerrancy, here’s pastoral counsel: Submit to Scripture’s authority even while working through your hard questions. Don’t wait for perfect understanding before obeying what’s clear. Read Scripture, and let it read you, for “the word of God is living and active, sharper than any two-edged sword” (Hebrews 4:12).

Let’s trust the Holy Spirit to illumine Scripture’s truth over time. Let’s wrestle alongside mature believers and learn from church history’s wisdom. Most importantly, let’s keep our eyes on Christ, the Word made flesh (John 1:14). Our salvation depends on him, not on having every doctrine perfected. Let’s press into Scripture rather than away from it, and watch how God meets us there.

RELATED FAQs

What do prominent Reformed scholars today say about inerrancy? Scholars like Michael Horton, Kevin Vanhoozer, and DA Carson affirm inerrancy while emphasising sophisticated hermeneutics. They argue inerrancy must account for literary genre, ancient conventions, and authorial intent rather than imposing modern standards on ancient texts. Vanhoozer speaks of Scripture’s “communicative action”—God accomplishes things through Bible texts that go beyond mere information transfer. These scholars maintain that a robust doctrine of Scripture protects gospel fidelity while avoiding wooden literalism that misreads the text.

- Did the early church fathers believe in inerrancy? The early church fathers consistently affirmed Scripture’s divine origin and complete truthfulness, though they didn’t use the term “inerrancy” as we do today. Augustine famously wrote that if he found a genuine error in Scripture, he would assume either the manuscript was corrupted, the translation faulty, or his own understanding inadequate. Origen, Chrysostom, and Jerome all treated Scripture as entirely reliable while recognising interpretive challenges. The consensus among the early fathers was clear: Scripture, being God-breathed, cannot err in what it teaches, even when interpretation proves difficult.

- How does inerrancy relate to textual variants in manuscripts? Inerrancy applies to the original manuscripts (autographa), not to copies, translations, or transmissions. We possess thousands of biblical manuscripts with minor variations—mostly spelling differences or word order changes—but no doctrine depends on disputed passages. Text-critical scholarship has been remarkably successful at reconstructing the original text with over 99% certainty. The existence of variants doesn’t undermine inerrancy; rather, the abundance of manuscripts gives us extraordinary confidence in what the Bible authors actually wrote.

What about apparent contradictions, like different Gospel accounts? Apparent contradictions often dissolve when we understand ancient biographical conventions, which valued theological truth over strict chronological precision. The Gospels are bios literature—interpretive portraits, not modern police reports demanding identical wording. Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John wrote from different perspectives, for different audiences, emphasising different themes, much like four reporters capturing the same soccer match from various angles. Harmonisation isn’t always necessary; complementary accounts provide richer, multi-dimensional testimony to Christ’s life and work.

- Can we accept evolution and still affirm biblical inerrancy? This remains a debated question within Reformed circles, with scholars like Tim Keller and John Walton arguing for compatibility while others like Ligon Duncan maintain young-earth creationism. Those affirming evolutionary creation argue Genesis 1-2 teaches theological truths about God as Creator using ancient Near Eastern literary forms, not modern scientific descriptions. They contend inerrancy means Scripture accurately teaches what it intends to teach—primarily theological and moral truth. However, others argue that a historical Adam and special creation are essential to biblical theology, making this an ongoing intramural discussion among inerrantists.

- What’s the difference between inerrancy and infallibility? Infallibility means Scripture won’t lead us astray in matters of faith and practice—it’s a trustworthy guide for salvation and godly living. Inerrancy makes the stronger claim that Scripture is entirely truthful in everything it affirms, including historical and scientific matters when properly understood. Some evangelicals embrace infallibility while questioning inerrancy, arguing Scripture’s theological reliability is what matters most. Reformed theologians typically affirm both, seeing inerrancy as the logical foundation for infallibility: if Scripture errs in earthly things, how can we trust it for heavenly things (John 3:12)?

How did the doctrine of inerrancy develop historically? While the early church affirmed Scripture’s divine truthfulness, the formal doctrine of inerrancy developed more explicitly during the Reformation and later in response to Enlightenment scepticism. The Protestant Reformers insisted on sola Scriptura—Scripture alone as the final authority—which required Scripture’s complete reliability. The Princeton theologians (Charles Hodge, BB Warfield) articulated inerrancy more precisely in the 19th century against liberal theology’s rising challenges. The 1978 Chicago Statement represents the most detailed modern formulation, though it articulates what the church has implicitly believed throughout history: God’s Word is entirely trustworthy.

OUR RELATED POSTS

- Is the Bible’s Inerrancy Defensible At All?

- Inerrancy Vs Infallibility: Which Does Scripture Demand We Affirm?

- Bible Inerrancy Explained: Answering Today’s Toughest Challenges

Editor's Pick

Why Do People Hate the Doctrine of Election?

…WHEN THEY REALLY SHOULDN’T Few Bible doctrines provoke stronger reactions than election. The idea that God chose some for salvation [...]

The Doctrine of Providence: Does God Really Govern All Things?

You’re sitting in the doctor’s office when the diagnosis lands like a thunderclap. Your mind races: Why this? Why now? [...]

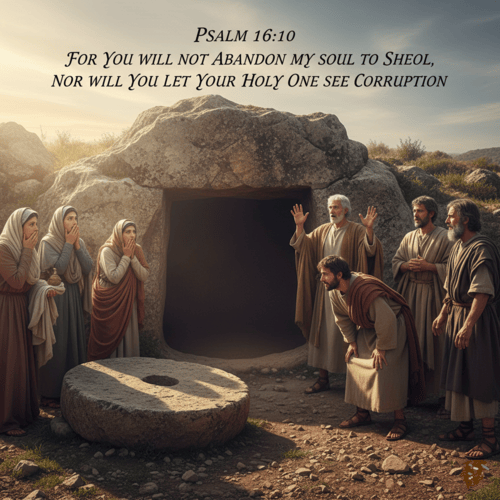

No Decay, No Defeat: What It Means That Christ’s Body Saw No Corruption

On the Day of Pentecost, Peter stood before thousands and made a startling claim: David's body decayed in the tomb, [...]

SUPPORT US:

Feel the Holy Spirit's gentle nudge to partner with us?

Donate Online:

Account Name: TRUTHS TO DIE FOR FOUNDATION

Account Number: 10243565459

Bank IFSC: IDFB0043391

Bank Name: IDFC FIRST BANK