Conspiracy Theory: Were Early Christian Writers Seeking Power?

*Editor’s Note: This post is part of our series, ‘Satan’s Lies: Common Deceptions in the Church Today’…

Were early Christian writers seeking power? The notion the early Christian writers collaborated to create a powerful religious movement has captured imaginations for centuries. Did the authors conspire together to gain power, or were their efforts a genuine reflection of their faith and convictions? As we examine the historical evidence, a more complex picture emerges that challenges these conspiracy narratives…

Join us as we delve into this intriguing inquiry. And uncover the truth from Satan’s lie.

CONSIDER FIRST: THE PRACTICAL IMPOSSIBILITY OF COORDINATION

Geographic Dispersion: The New Testament writers were scattered across thousands of miles in the Roman Empire—from Rome to Asia Minor to Palestine. This vast separation made regular communication nearly impossible, with Paul writing from various cities, John likely in Ephesus, and others spread throughout the Mediterranean world.

Timeline Analysis: The New Testament documents were written over a span of approximately 50 years, with Paul’s earliest letters appearing around 50 AD and John’s writings coming near the end of the first century. This extended timeline would have required maintaining consistency in fabrication across multiple decades and generations of early Christians.

Communication Limitations: First-century communication relied on hand-delivered letters that could take months to reach their destination. The Roman road system, while impressive, still meant that messages between distant cities could take weeks or months to arrive. The practical limitations would have made coordinating a complex theological narrative nearly impossible.

Different Audiences and Purposes: Each New Testament document addresses specific local situations and distinct audiences, from Paul’s letter to slave-owners to John’s apocalyptic visions. The texts show clear evidence of addressing real, local concerns rather than following a centralised narrative plan.

THE HUMAN COST: WHAT THE WRITERS GAINED AND LOST

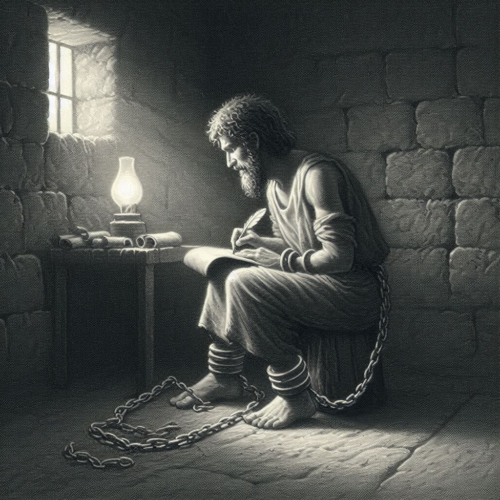

Personal Losses: The New Testament writers faced severe persecution, loss of social status, and economic hardship. Paul gave up a prestigious position in Jewish society to face repeated imprisonment and eventual execution. Rather than gaining power, the writers consistently lost social standing and material comfort.

Persecution Patterns: Historical records show systematic persecution of early Christian leaders under multiple Roman emperors. Writers such as Peter and Paul were executed in Rome, while others faced imprisonment, exile, and torture. These patterns of persecution demonstrate that writing these texts led to loss of power rather than gain.

Martyrdom Evidence: Early historical sources document the execution of most of the New Testament writers. Extra-biblical sources confirm that these writers maintained their testimony even under threat of death. This willingness to die argues strongly against a conspiracy for power.

Movement Characteristics: The early Christian movement consistently advocated for servant leadership, sacrifice, and rejection of worldly power. These characteristics stand in stark contrast to typical power-seeking movements of the time. The focus on serving others rather than accumulating authority challenges conspiracy theories.

LITERARY EVIDENCE AGAINST CONSPIRACY

- Writing Styles and Vocabulary: Each New Testament writer displays distinct literary characteristics and vocabulary preferences. John’s writing style differs markedly from Paul’s, while Luke’s educated Greek contrasts with Peter’s simpler expression. These individual writing fingerprints suggest authentic individual authorship rather than coordinated composition.

- Surface Contradictions: The gospel accounts contain apparent discrepancies in details that a coordinated conspiracy would likely have eliminated. These include different sequences of events and varying details in parallel accounts. The presence of these surface tensions suggests independent reporting rather than careful coordination.

- Embarrassing Details: The texts preserve unflattering details about key leaders – Peter’s denials, Paul’s previous persecution of Christians, the disciples’ frequent misunderstandings. A coordinated effort to build authority would likely have omitted these embarrassing elements. Their inclusion suggests commitment to truthful reporting over image management.

HISTORICAL CONTEXT AND EXTERNAL VERIFICATION

Contemporary Non-Christian Sources: Writers like Josephus, Tacitus, and Pliny the Younger provide independent confirmation of early Christian beliefs and practices. These secular historians documented the rapid spread of Christianity and its core claims, often from a sceptical or hostile perspective. Their accounts align with the New Testament’s basic historical framework while offering no hint of coordinated deception.

Archaeological Confirmations: Archaeological discoveries consistently validate the New Testament’s historical and cultural details. From the discovery of Pontius Pilate’s inscription to confirmation of specific civic titles and local customs, physical evidence supports the writers’ intimate knowledge of their settings. This accuracy in minor details suggests faithful reporting rather than fictional creation.

Early Church Growth Patterns: The explosive growth of Christianity across social classes and geographic regions follows patterns typical of genuine movements rather than manufactured ones. The faith spread rapidly despite persecution, often through social networks and personal testimony. This organic growth pattern contradicts the notion of centrally controlled expansion.

Enemy Attestation: Early opponents of Christianity attacked specific claims but never suggested a conspiracy among its founders. Contemporary critics challenged the resurrection and deity of Christ but accepted the basic historical framework of Christianity’s origins. Their silence about any conspiracy is telling.

THE NATURE OF THE WRITINGS

Lack of Political Agenda: The New Testament texts consistently avoid political power plays common to the era. Rather than advocating rebellion against Rome or establishing political structures, they focus on spiritual transformation and ethical living. This absence of political manoeuvring argues against a power-seeking agenda.

Counter-Cultural Teachings: The writings promote values that often opposed both Jewish and Greco-Roman cultural norms. From elevating the status of women to rejecting social hierarchy in spiritual community, these counter-cultural elements would have hindered rather than helped any bid for power.

Emphasis on Servant Leadership: The documents repeatedly emphasise humble service over authoritative control. Jesus’ teaching about leadership through service, demonstrated in foot washing and sacrificial death, sets a pattern that appears consistently through all New Testament texts. This emphasis contradicts typical power-acquisition strategies.

Treatment of Wealth and Power: Rather than promising material gain or social advancement, the texts often warn about the dangers of wealth and criticize power abuse. The consistent critique of materialism and emphasis on spiritual riches over temporal power suggests aims other than personal advancement.

CONCLUSION: WERE EARLY CHRISTIAN WRITERS SEEKING POWER?

The evidence reveals a striking paradox: far from orchestrating a power grab, the New Testament writers created documents that consistently undermined their own potential for earthly influence and authority. Their geographic separation, willingness to face persecution, and commitment to servant leadership all point to conviction rather than conspiracy. The historical and archaeological record, combined with the counterintuitive nature of their message, suggests these writers were driven by something far more compelling than a desire for power—they appear to have been convinced they were witnesses to events that would transform human history. Whether one accepts their claims or not, the evidence strongly suggests these were not the calculated works of power-seeking conspirators, but rather the testimonies of people convinced they had encountered something—or Someone—worth dying for.

WERE EARLY CHRISTIAN WRITERS SEEKING POWER?—RELATED FAQs

How quickly did copies of New Testament writings spread across the ancient world? Early manuscript evidence shows remarkable distribution speed, with fragments found across the Mediterranean within decades of original composition. The rapid spread across different regions and language groups would have made controlled editing or conspiracy virtually impossible, as communities across vast distances possessed and treasured their own copies.

Why are there so many ancient copies of New Testament texts compared to other ancient works? The New Testament texts have over 5,800 Greek manuscripts and over 20,000 versions in other languages, far exceeding any other ancient document. This extraordinary number of copies reflects both the texts’ rapid distribution and the early Christian community’s commitment to careful preservation, making systematic alteration practically impossible.

How consistent are early manuscripts in their core message? While scribal variations exist in early manuscripts, the core message and essential doctrines remain remarkably consistent across thousands of copies. The variations we do find actually strengthen the case against conspiracy, as they show natural transmission patterns rather than centralised control.

How did early Christian communities preserve their texts? Local churches treated these documents as precious resources, creating careful copies and regularly reading them in public gatherings. This public reading practice made unauthorised changes virtually impossible, as the congregation would have noticed any significant alterations to familiar texts.

What external sources quote from the New Testament in the first few centuries? Early church writers like Clement, Ignatius, and Polycarp extensively quoted New Testament texts, providing an external check on their content. These quotations are so extensive that most of the New Testament could be reconstructed from their writings alone, demonstrating the fixed nature of the text by the early second century.

Why would a power conspiracy include embarrassing details about its leaders? The preservation of unflattering details about church leaders—including cowardice, doubt, and failures—strongly argues against a conspiracy for power. Leaders crafting a narrative for control typically portray themselves in the best possible light, making these honest admissions particularly significant.

How do early Christian writings compare to actual power-seeking religious texts from the same era? Unlike contemporary power-seeking religious texts, which typically promised earthly benefits and political influence, New Testament writings consistently warned followers to expect persecution and sacrifice. This stark contrast to typical power-seeking literature of the period suggests different motivations entirely.

WERE EARLY CHRISTIAN WRITERS SEEKING POWER?—OUR RELATED POSTS

Editor's Pick

SUPPORT US:

Feel the Holy Spirit's gentle nudge to partner with us?

Donate Online:

Account Name: TRUTHS TO DIE FOR FOUNDATION

Account Number: 10243565459

Bank IFSC: IDFB0043391

Bank Name: IDFC FIRST BANK