Deeply Moved: Why Did Jesus Weep at Lazarus’s Tomb?

“Jesus wept.” Scripture’s shortest verse (John 11:35) presents one of its most profound mysteries. Picture the scene: Jesus stands at the grave of Lazarus in Bethany, fully aware that in moments His friend will walk out alive. The miracle has already been decided. The outcome is certain. Yet Jesus—the Author of life itself—is sobbing.

Why? If anyone ever had reason to stay composed at a graveside, surely it’s the One who holds the keys to death and Hades. He wrote this script. He knows it has a triumphant ending. So why the tears? Why the trembling? Why the deep, groaning fury the Greek text reveals churning in His spirit? The answer isn’t simple, but it’s no loose thread in the narrative either—no detail the Author forgot to resolve. This is intentional. This is revelation. Come, let’s discover why the God-man wept.

THE CONTEXT: THAT INTENSE MOMENT

John is careful to tell us exactly what Jesus sees: Mary, the sister of Lazarus, falls at Jesus’s feet sobbing, and the crowd of mourners begins to wail with her (John 11:33). When Jesus sees it, He is “deeply moved in His spirit and greatly troubled.” The Greek verb behind “deeply moved” (enebrimēsato) is intense—it’s the same word used for a horse snorting in battle or for righteous indignation (Mark 1:43; 14:5). This isn’t gentle sadness. Something in Jesus is clearly recoiling with fury.

THE TEARS OF TRUE HUMANITY

The Incarnation wasn’t a divine costume. When God became man in Jesus Christ, He took on genuine human nature—including real human emotions. Hebrews 4:15 tells us we have a High Priest in Jesus “who sympathises with our weaknesses,” who was “tempted in every way, just as we are—yet He was without sin.”

Christ’s tears authenticate His humanity. He isn’t performing grief; He is experiencing it. When Jesus sees Mary weeping and the mourners wailing (John 11:33), He enters fully into their sorrow. This is the Reformed doctrine of the hypostatic union in action—Jesus is fully God and fully man, not diminished in either nature.

His tears validate something crucial for us today: grief isn’t a failure of faith. Jesus possessed absolute certainty about what He was about to do, yet He still wept. We don’t honour God by suppressing legitimate sorrow or pretending death doesn’t hurt. Our Saviour felt the weight of loss, and in doing so, He sanctifies our tears.

THE FURY AGAINST SIN’S DEVASTATION

But here’s where the English translations miss something vital. When John 11:33 says Jesus was “deeply moved,” the Greek verb, enebrimēsato—suggests He was “snorting with anger” or “moved with indignation.” This same intense word appears again in verse 38. Jesus wasn’t just sad. He was furious.

At what? At death itself—the “last enemy” (1 Corinthians 15:26) that invaded God’s good creation. Death is an unnatural intruder, the consequence of sin that entered the world through Adam’s rebellion (Romans 5:12). Standing before Lazarus’s tomb, Jesus confronted the full horror of the Fall’s devastation. Every funeral, every grave, every tear shed over a corpse represents everything opposed to God’s original design for humanity.

This holy anger reveals Jesus’s character. We see the same righteous fury when He cleansed the temple (John 2), driving out those who corrupted His Father’s house. At Lazarus’s tomb, He faces an even greater corruption—death’s mockery of the life God intended. His fury foreshadows the cross, where He would deal death its fatal blow, absorbing sin’s curse and breaking the grave’s power forever.

SOLIDARITY BEFORE VICTORY

Here’s the beautiful paradox: Jesus doesn’t bypass the emotional reality of death to get to the miracle. He enters the valley with us before conquering it. This models the “already/not yet” tension of redemption—we possess resurrection power now but await our bodily glorification.

John Owen, the Puritan theologian, wrote Christ’s sufferings make Him the perfect High Priest, one who truly understands our frame. Jesus’s tears declare: “I am with you in this darkness, not merely above it.” He doesn’t minimise present suffering because future glory is certain. Even the raising of Lazarus is only a sign, not the final answer—Lazarus, after all, would die again. But this miracle points forward to the day when death is abolished permanently.

THE PROMISE FOR EVERY GRAVE WE STAND BESIDE

Because Jesus once stood weeping outside a tomb in Bethany, every believer can know three unshakable truths:

- Death is not natural. It is an outrage that still angers our Saviour. When we feel death is wrong—that gut-level revulsion we feel at every grave—we’re feeling what Jesus felt. Our instinct is right. Death was never part of God’s plan, and His fury at Lazarus’s tomb proves He hasn’t made peace with it either.

- Our tears are never alone. The Man of Sorrows carries every one. Psalm 56:8 tells us God collects our tears in a bottle—He doesn’t waste our grief or dismiss our pain. The Jesus who wept at Bethany weeps still with those who mourn. We are never crying by ourselves.

- The final “Lazarus moment” is coming. One day soon the voice that shattered death at Bethany will thunder again, and every grave will give up its dead. Then “He will wipe away every tear from their eyes, and death shall be no more” (Revelation 21:4). What happened for Lazarus temporarily will happen for all believers permanently.

SOLIDARITY BEFORE VICTORY

The shortest verse in the Bible carries the longest shadow of grace. Jesus wept because He is truly human, feeling our pain with perfect empathy. Jesus raged because He is truly holy, hating the sin that shattered His world. Both responses flow from perfect love.

Charles Spurgeon closed one of his sermons on this text with a sentence that still rings true: “Jesus wept that we might never weep again in the same way.” At Lazarus’s tomb, God incarnate wept at death before destroying it. The same Jesus who stood weeping with Mary will one day dry every eye. The same Jesus who raged at the tomb will banish death forever. This is our certain hope. This is why He wept.

The Westminster Shorter Catechism teaches us sin brings misery and demands God’s just response. Jesus’s anger at the tomb shows us God doesn’t just shrug at death. He hates it. He rages against it. And ultimately, He destroys it.

RELATED FAQs

Did Jesus delay coming to Lazarus on purpose? Yes, and John’s Gospel makes this clear. Jesus explicitly stayed two more days after hearing Lazarus was sick (John 11:6), and He tells His disciples Lazarus’s death happened “so that you may believe” (v 15). DA Carson notes Jesus’s delay wasn’t cruelty but divine timing—He orchestrated events to maximise God’s glory and deepen faith. The four-day period (v 17) was also significant in Jewish thought, as decomposition was believed to begin after three days, making the miracle undeniable.

- Why does John mention Jesus was “deeply moved” twice? The repetition of ‘deeply moved’ in verses 33 and 38 is John’s way of emphasising the intensity and persistence of Jesus’s emotion. Commentator Leon Morris suggests the double mention shows this wasn’t a fleeting reaction but a sustained response—Jesus’s anger didn’t dissipate as He approached the tomb. The first instance occurs when He sees the mourners; the second when He reaches the grave itself. This literary technique highlights Jesus’s fury at death grew stronger, not weaker, as He drew closer to confronting it directly.

- Were the mourners’ tears genuine, or was Jesus angry at professional mourners? This is debated among scholars. Some Reformed interpreters, including John MacArthur, suggest Jesus may have been partly disturbed by the theatrical nature of first-century professional mourning, which could be performative rather than heartfelt. However, Mary’s tears were clearly genuine (v 33), and Jesus’s response seems directed at death itself rather than the mourners. Most contemporary exegetes see Jesus’s anger as cosmic—aimed at sin’s destructive power—rather than at the people around Him, whose grief He validated by sharing it.

Why did Jesus ask where Lazarus was laid if He’s omniscient? Jesus’s question “Where have you laid him?” (v 34) wasn’t for information but for participation. Herman Bavinck emphasised Jesus’s questions throughout the Gospels serve pedagogical and relational purposes, not to fill gaps in His knowledge. By asking, Jesus invites the mourners into the miracle that’s about to unfold. He also models genuine human interaction—even with divine foreknowledge, He engages people naturally. The question draws Mary, Martha, and the crowd to the tomb where they’ll witness God’s glory.

- Is there significance to Jesus being “troubled in spirit” (v 33)? Absolutely. The phrase echoes Jesus’s language in John 12:27 (“Now is my soul troubled”) and 13:21 (troubled about Judas’s betrayal), connecting Lazarus’s tomb to the cross. New Testament scholar Richard Bauckham argues this “troubling” reveals Jesus’s internal wrestling with the cosmic battle against evil. Jesus isn’t emotionally detached or serenely floating above human experience—He feels the weight of confronting Satan’s kingdom. This “troubled spirit” shows the cost of engaging evil, even for the Son of God, and foreshadows the agony He’ll experience in Gethsemane.

- Why did Jesus pray aloud before raising Lazarus? Jesus explicitly says He prayed aloud “for the sake of the people standing here, that they may believe that you sent me” (v. 42). He didn’t need to voice this prayer for His own sake—He already knew the Father heard Him (v. 42). Michael Horton points out this demonstrates Jesus’s consistent mission: revealing the Father. The public prayer served as both testimony and teaching. It showed Jesus’s power comes from His relationship with the Father, not from magical incantation or independent authority. It authenticated His divine mission before He performed the miracle.

How does this story connect to Jesus’s own resurrection? Lazarus’s resurrection is a preview, not a duplicate, of Christ’s resurrection. New Testament scholar NT Wright notes crucial differences: Lazarus was resuscitated to mortal life and would die again, while Jesus rose to immortal, glorified life. However, John deliberately structures this as the seventh and climactic sign in his Gospel, pointing toward Jesus’s own victory. Jesus’s statement “I am the resurrection and the life” (v 25) isn’t just about raising others—it’s a claim about His own nature. By raising Lazarus, Jesus demonstrated the power He would unleash on Easter morning. At Calvary and the empty tomb, He would accomplish what Bethany only foreshadowed: death’s permanent defeat.

OUR RELATED POSTS

Editor's Pick

Why Do People Hate the Doctrine of Election?

…WHEN THEY REALLY SHOULDN’T Few Bible doctrines provoke stronger reactions than election. The idea that God chose some for salvation [...]

The Doctrine of Providence: Does God Really Govern All Things?

You’re sitting in the doctor’s office when the diagnosis lands like a thunderclap. Your mind races: Why this? Why now? [...]

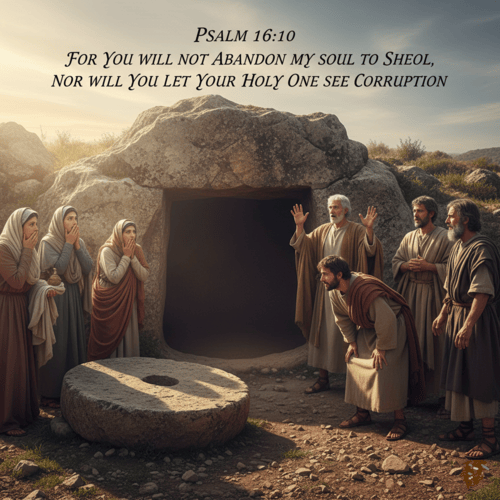

No Decay, No Defeat: What It Means That Christ’s Body Saw No Corruption

On the Day of Pentecost, Peter stood before thousands and made a startling claim: David's body decayed in the tomb, [...]

SUPPORT US:

Feel the Holy Spirit's gentle nudge to partner with us?

Donate Online:

Account Name: TRUTHS TO DIE FOR FOUNDATION

Account Number: 10243565459

Bank IFSC: IDFB0043391

Bank Name: IDFC FIRST BANK