Do Even Small Sins Deserve Eternal Damnation?

“It was just a white lie.”

“I only lost my temper for a moment.”

“Compared to murderers and rapists, I’m basically a good person.”

We’ve all heard such justifications—perhaps we’ve made them ourselves. The follow-up question stumps most believers: Does God really condemn people to eternal hell for what are minor infractions? Does God really condemn people to eternal hell for what are minor infractions?Most modern voices decree God must be a cosmic tyrant, cruel and vindictive. But what if our entire frame of reference is wrong?

From the Bible’s perspective, yes—even what we call “small” sins deserve eternal punishment. Not because God is cruel, but because all sin is an infinite offense against an infinitely holy God. This reality doesn’t diminish God’s character; it magnifies both His perfect justice and the breathtaking glory of His grace. Let’s explore why God’s holiness demands this, what Scripture clearly teaches, and how this doctrine ultimately points us to the cross.

THE HOLINESS OF GOD: THE FOUNDATION OF ALL JUSTICE

The seraphim in Isaiah’s vision don’t cry “Powerful, powerful, powerful” or even “Loving, loving, loving”—they proclaim “Holy, holy, holy is the LORD of hosts” (Isaiah 6:3). As RC Sproul masterfully argues in The Holiness of God, this absolute, blazing purity is God’s defining attribute. His holiness isn’t merely moral cleanliness; it’s the infinite perfection that makes Him utterly separate from all creation.

Here’s the crucial insight: the severity of any crime corresponds to the dignity of the one offended. Strike your neighbour, and you face assault charges. Strike a governor, and the penalty increases. Strike a king, and you’ve committed treason. Now extrapolate infinitely: sin against an eternal, infinitely holy God demands an eternal consequence. As John Piper explains, sins are “infinitely offensive” not because of their duration but because of whom they offend.

The Westminster Confession states it plainly: “Every sin, both original and actual… deserveth God’s wrath and curse, both in this life, and that which is to come” (6.6). This isn’t arbitrary divine overreaction—it’s the mathematics of perfect justice. Romans 3:23 reminds us “all have sinned and fall short of the glory of God.” That glory, that holiness, sets the standard. What seems like divine cruelty is actually the logical outworking of who God truly is.

THE GRAVITY OF SIN: COSMIC TREASON, NOT MINOR MISTAKES

Our problem is we measure sin on a human scale. We rank transgressions from “not so bad” to “really terrible,” imagining God should grade on a curve. But Reformed theology, grounded in Scripture’s doctrine of total depravity, reveals a different reality: all sin is fundamentally rebellion against God’s rightful authority.

David understood this. After adultery and murder, he cried, “Against You, You only, have I sinned” (Psalm 51:4). Sin isn’t primarily about horizontal harm between humans—it’s vertical treason against the King of the universe. Jeremiah 17:9 exposes the root: “The heart is deceitful above all things, and desperately sick.” Sin flows from a heart condition that says to God, “I want my will, not Yours.”

Romans 6:23 gives us the ledger: “The wages of sin is death.” Not temporary death, but eternal separation from the source of life itself. As Jonathan Edwards preached in “Sinners in the Hands of an Angry God,” even one sin merits infinite wrath because it’s committed against infinite majesty. The Heidelberg Catechism (Q&A 11) calls sin “so heinous” that God’s justice requires satisfaction against it.

Jesus Himself demolishes our categories of “small” versus “big” sins. In Matthew 5:21-22, He equates anger with murder, lust with adultery. Before God’s penetrating holiness, there are no minor infractions—only varying expressions of the same cosmic rebellion.

BIBLICAL EVIDENCE: SCRIPTURE’S UNAVOIDABLE TESTIMONY

Jesus spoke more about hell than anyone in Scripture, and His warnings were, as Piper notes, “prolific and devastating.” In Matthew 25:46, He describes “eternal punishment” for the unrighteous—the same Greek word (aionios) used for eternal life, emphasising permanence. Mark 9:48 speaks of fire that is “not quenched,” unending judgment for unrepentant sin.

The apostles echo this solemnity. Paul writes of “everlasting destruction from the presence of the Lord” (2 Thessalonians 1:9). Revelation 14:11 describes torment where “the smoke of their torment goes up forever and ever.” This isn’t poetic exaggeration—it’s consistent biblical testimony about the stakes of sin.

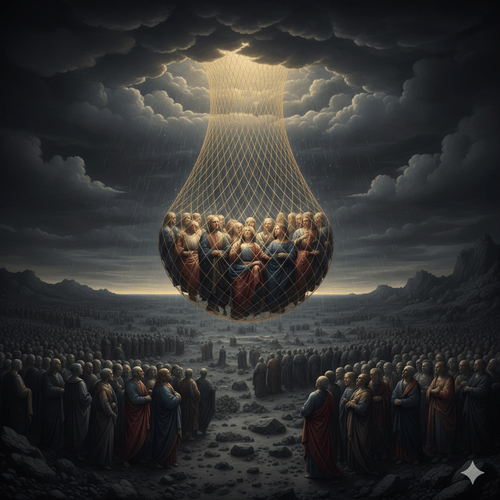

Reformed interpretation holds God’s wrath is retributive, not merely rehabilitative. The Westminster standards teach that punishment is rendered “for sin’s sake” (6.6), because God’s justice demands full payment. Combined with the doctrines of total depravity (all deserve condemnation) and unconditional election (salvation comes entirely by grace), we see a consistent framework: humanity stands guilty before infinite holiness, unable to save itself.

NOT CRUELTY, BUT JUSTICE—AND UNFATHOMABLE MERCY

Is God cruel? Only if justice itself is cruel. As Sproul observed, to minimise sin is to minimise why Christ had to die. Sin is that serious—serious enough to require God’s own Son on a cross. The charge of cruelty reveals our inability to grasp infinite holiness with finite minds (Isaiah 55:8-9).

Consider this: God doesn’t immediately execute judgement the moment we sin. He extends common grace, sunshine, and rain to all. He offers salvation freely to any who will receive it. “God shows his love for us in that while we were still sinners, Christ died for us” (Romans 5:8). Piper argues eternal punishment underscores the magnitude of rejecting infinite love. God’s judgement isn’t arbitrary—it’s the just response to creatures who spurn their Creator.

THE GOSPEL’S URGENT, BEAUTIFUL HOPE

Yes, even small sins deserve eternal damnation because they’re offenses against an infinitely holy God. But here’s the glorious twist: Christ Jesus bore that infinite punishment in our place. “For our sake he made him to be sin who knew no sin, so that in him we might become the righteousness of God” (2 Corinthians 5:21).

The very doctrine that seems harsh is what makes grace so magnificent. Romans 6:23 doesn’t end with death—it concludes, “but the free gift of God is eternal life in Christ Jesus our Lord.” This isn’t universalism that cheapens sin; it’s costly grace that magnifies mercy.

The call is urgent: repent and believe. The same holiness that demands eternal justice offers eternal life through Jesus. Rather than making God a tyrant, this doctrine reveals Him as both perfectly just and lavishly merciful—a Saviour worth knowing, trusting, and worshiping forever.

DO SMALL SINS DESERVE ETERNAL DAMNATION? RELATED FAQs

What about people who never heard the gospel? Is it fair they go to hell for “small” sins when they had no chance? Reformed theology distinguishes between God’s revealed will (Scripture) and His secret will (sovereign decrees), but agrees no one is condemned for lack of opportunity—they’re condemned for their sin against the light they do have. Romans 1:18-20 teaches God’s eternal power and divine nature are evident in creation, making humanity “without excuse,” and Romans 2:14-15 shows even Gentiles have God’s law “written on their hearts.” Contemporary Reformed theologian Michael Horton emphasises the question isn’t whether people have heard of Jesus, but whether they’ve honoured the God they do know through nature and conscience—and Scripture’s answer is a universal “no” (Romans 3:10-12). The real scandal isn’t that some lack gospel access; it’s that God mercifully saves anyone at all.

- Doesn’t infinite punishment for finite sins violate proportionality? How can 70 years of sin equal eternal hell? This objection assumes sin’s gravity is measured by its duration rather than the dignity of the one offended—a category error Reformed theologians consistently challenge. Robert Letham, in Systematic Theology, argues sins aren’t finite because they’re committed in time; they’re infinite because they’re committed against an eternal, infinite Being whose holiness has no limit. Think of it this way: treason against an earthly king might warrant life imprisonment not because the act took a long time, but because of who was betrayed; how much more does rebellion against the King of kings deserve eternal consequences? Jonathan Edwards framed it memorably: the unrepentant continue sinning and rejecting God forever in hell, so punishment continues—it’s not disproportionate but fitting, as the sinner never ceases to be God’s enemy.

- Did John Calvin really believe unbaptised infants go to hell? What do Reformed theologians say about people with diminished capacity? Calvin actually rejected the notion that all unbaptised infants are damned, a significant departure from some medieval views—he believed God could save elect infants through extraordinary means apart from baptism (Institutes 4.16.17-18). Modern Reformed scholars like Sinclair Ferguson and Kevin DeYoung affirm that God judges according to knowledge and capacity; Westminster Confession 10.3 explicitly states that “elect infants, dying in infancy, are regenerated and saved by Christ,” though it wisely doesn’t speculate on numbers. Those with severe cognitive disabilities who cannot understand the gospel fall under similar principles—God’s justice is always calibrated to what people actually can know and do, not impossible standards. The Reformed position trusts God’s wisdom in these mysteries while affirming that no one suffers unjustly; if God saves infants or the intellectually disabled who cannot believe, it’s pure grace, and if He doesn’t, it’s perfect justice.

I’d rather not trust a God who punishes even minor sins eternally in hell. How do Reformed Christians respond to this objection? Reformed theologian JI Packer would gently but firmly reply: we don’t get to choose what God is like based on our preferences—we must reckon with who He actually is according to His self-revelation. The God of Scripture isn’t a cosmic butler who exists to meet our comfort standards; He’s the holy Creator before whom we’re accountable, and our discomfort with His justice reveals not His deficiency but our inability to grasp how serious sin truly is and how holy He truly is. DA Carson notes that saying “I’d rather not trust this God” is itself an act of moral rebellion—it’s deciding I will be judge over God, determining what He should be like, which is the very essence of sin that deserves judgement. Here’s the startling grace: God offers us Jesus, who endured the wrath that our sin deserves, so we can trust Him not as a tame deity who winks at sin, but as a Saviour who conquered it—and that substitutionary sacrifice only makes sense if the punishment was really as severe as He bore.

- What about annihilationism—the view that the unsaved simply cease to exist rather than suffer eternally? Don’t some evangelical scholars hold this? Yes, some evangelicals like John Stott and more recently, scholars associated with the Rethinking Hell movement, have argued for conditional immortality (annihilationism), suggesting hell results in the complete destruction of the wicked rather than conscious eternal torment. However, mainstream Reformed theologians like Robert Peterson (Hell on Trial) and Christopher Morgan vigorously defend eternal conscious punishment, arguing that biblical language of “eternal fire” (Matthew 25:41), “eternal destruction” (2 Thessalonians 1:9), and the “smoke of their torment” rising “forever and ever” (Revelation 14:11) clearly indicates ongoing consciousness, not extinction. The Reformed position emphasises that Jesus consistently used present-tense, ongoing language—“their worm does not die” (Mark 9:48)—and that annihilation would actually be a mercy incompatible with justice for those who perpetually reject God. If the wicked simply winked out of existence, it would undercut both the seriousness of sin and the magnitude of the salvation Christ purchased—if hell isn’t really that terrible, was the cross really necessary?

- How does God’s love square with eternal hell? Doesn’t 1 John 4:8 say “God is love”? Reformed theologian Donald Macleod addresses this brilliantly: God’s love doesn’t negate His other attributes—His holiness, justice, and wrath are equally ultimate and essential to His character. God is indeed love (1 John 4:8), but John also writes that “God is light, and in him is no darkness at all” (1 John 1:5)—these aren’t competing truths but complementary ones that must be held in tension. Timothy Keller explains that God’s love is holy love, not sentimental tolerance; He loves righteousness so intensely that He must hate evil, and His love for His glory and His people’s good requires that rebellion be judged. The cross itself is where God’s love and justice kiss—He didn’t abandon justice to show love, nor abandon love to show justice; instead, He bore His own righteous wrath against sin in Christ so that His love could save sinners without compromising holiness, proving that eternal punishment is what divine love itself demanded before mercy could flow.

Are there degrees of punishment in hell, or is everyone equally tormented? If there are degrees, doesn’t that admit some sins are “smaller”? Yes, Scripture clearly teaches degrees of punishment—Jesus said it will be “more bearable” for Sodom than for cities that rejected His ministry (Matthew 11:24), and those who knew their master’s will but didn’t do it “will be beaten with many blows,” while those who didn’t know “will be beaten with few” (Luke 12:47-48). Reformed theologian Wayne Grudem explains that this does mean some sins bring greater condemnation than others, but—and this is crucial—all sins still deserve eternal punishment, just as all criminals might receive different sentence lengths yet all justly go to prison. Jonathan Edwards described it as an infinitely deep ocean where some wade and some plunge to unfathomable depths, but all are drowning; the varying severity reflects differing degrees of guilt, but the eternal duration reflects that even the “smallest” sin is an infinite offense against infinite holiness. This actually makes God’s justice more precise, not less—He calibrates punishment exactly to what each person deserves, which means even the “easiest” damnation is still eternally dreadful and should drive us to the cross where Christ bore the full weight of God’s wrath, whether for “greater” or “lesser” sins.

DO SMALL SINS DESERVE ETERNAL DAMNATION? OUR RELATED POSTS

Editor's Pick

Why Do People Hate the Doctrine of Election?

…WHEN THEY REALLY SHOULDN’T Few Bible doctrines provoke stronger reactions than election. The idea that God chose some for salvation [...]

The Doctrine of Providence: Does God Really Govern All Things?

You’re sitting in the doctor’s office when the diagnosis lands like a thunderclap. Your mind races: Why this? Why now? [...]

No Decay, No Defeat: What It Means That Christ’s Body Saw No Corruption

On the Day of Pentecost, Peter stood before thousands and made a startling claim: David's body decayed in the tomb, [...]

SUPPORT US:

Feel the Holy Spirit's gentle nudge to partner with us?

Donate Online:

Account Name: TRUTHS TO DIE FOR FOUNDATION

Account Number: 10243565459

Bank IFSC: IDFB0043391

Bank Name: IDFC FIRST BANK