Saints and Sinners: Why Does the Bible Use Both Terms for Christians?

SAINTS BY ‘POSITION’ AND SINNERS BY CONDITION

Ever noticed in Paul’s letters how he addresses Christians as “saints” or “holy ones”? It can feel jarring to most of us. After all, we’re acutely aware of our daily struggles with sin. How can God possibly call such imperfect people “saints”?

The apparent contradiction strikes at the heart of the Christian experience and reveals something profound about God’s redemptive work. Let’s explore the tension from a Reformed perspective.

WHAT DOES “SAINT” ACTUALLY MEAN?

The word “saint” comes from the Greek word hagios—meaning “set apart” or “holy one.” When Paul writes to “the saints in Ephesus” (Ephesians 1:1) or “all the saints in Christ Jesus at Philippi” (Philippians 1:1), he’s not addressing a spiritual elite who’ve achieved moral perfection.

Far from it: he’s recognising their position in Christ. They—like all believers—have been set apart for God’s purposes. This is a status conferred upon them by God Himself, not earned by them.

JUSTIFIED, YET STILL SINNING

At the core of Reformed theology is the recognition that Christians possess a dual identity. As Martin Luther famously put it, we’re simul justus et peccator—simultaneously justified and sinners.

When God looks at believers, He sees them clothed in Christ’s righteousness. Paul explains this glorious truth in 2 Corinthians 5:21: “God made him who had no sin to be sin for us, so that in him we might become the righteousness of God.”

This is the doctrine of justification—the legal declaration that believers are righteous based not on their own merits but on Christ’s perfect life and sacrificial death. It’s a completed transaction with a stunning result: “Therefore, there is now no condemnation for those who are in Christ Jesus” (Romans 8:1).

THE ONGOING REALITY OF SANCTIFICATION

If justification is a one-time declaration, sanctification is an ongoing process. We’re declared holy in position, but we’re still being made holy in practice. This explains why the same Paul who calls believers “saints” also describes his own personal struggle with sin:

“I do not understand what I do. For what I want to do I do not do, but what I hate I do… For I have the desire to do what is good, but I cannot carry it out” (Romans 7:15, 18).

Sound familiar? Paul captures the universal Christian experience—we’re wanting to honour God but continually falling short. Yet the bitter struggle doesn’t negate our standing as saint. In fact, it’s evidence of the Holy Spirit’s work in us, creating a heightened awareness of—and hatred for—sin. And a deeper desire for holiness.

SAINTS AND SINNERS: ALREADY, BUT NOT YET

Reformed theology embraces the tension through what’s called the “already but not yet” paradigm. We’re already declared righteous in Christ, but we’re not yet fully transformed into His likeness.

The Westminster Confession of Faith, a key Reformed document, clearly distinguishes between justification and sanctification: “They, who are once effectually called, and regenerated, having a new heart, and a new spirit created in them, are further sanctified, really and personally, through the virtue of Christ’s death and resurrection, by His Word and Spirit dwelling in them… yet imperfectly in this life, there abiding still some remnants of corruption in every part.”

We live in the overlap of two ages: we’re legally transferred from the kingdom of darkness to the kingdom of light, yet still battling the remnants of our old fallen nature.

SAINTS AND SINNERS: WHAT THIS MEANS FOR US

The understanding that believers are “saints who sin” carries profound implications:

- Assurance Based on Christ, Not Performance: Our identity as a saint isn’t contingent on our spiritual performance. It’s secured by Christ’s finished work. On our worst days, even when sin feels most powerful, we remain clothed in Christ’s righteousness.

- Humility from Recognising Ongoing Sin: The persistence of sin in your life should produce humility, not despair. Even the apostle Paul—writer of much of the New Testament—acknowledged his ongoing struggle. If Paul needed grace daily, how much more do we?

- Growth Motivated by Gratitude, Not Fear: Your pursuit of holiness isn’t about earning God’s favour but responding to it. You don’t strive for obedience to become a saint; you strive because you already are one. As John puts it, “We love because he first loved us” (1 John 4:19).

CONCLUSION: THE BLESSED HOPE OF FULL TRANSFORMATION

The disconnect between our saintly position and our sinful condition won’t last forever—oh, how precious is the thought. Scripture promises one day our practice will catch up with our position:

“Dear friends, now we are children of God, and what we will be has not yet been made known. But we know that when Christ appears, we shall be like him, for we shall see him as he is” (1 John 3:2).

Until that day, we live in the painful tension of being saints who sin—perfectly loved, gradually transformed, and ultimately destined for complete holiness. That’s not a paradox. That’s grace.

SAINTS AND SINNERS: RELATED FAQs

Doesn’t the Catholic Church use “saint” differently than Protestants do? Yes, the Catholic tradition typically does reserve the term “saint” for those who’ve been officially canonised after death, having demonstrated “heroic virtue” and with miracles attributed to their intercession. The Reformed view, instead recognises all believers as saints as Scripture does, by virtue of their union with Christ, not because of extraordinary personal holiness or posthumous recognition. This reflects the biblical usage where Paul addresses entire congregations as “saints” despite their obvious spiritual struggles.

- If I’m already a “saint,” why should I bother fighting sin? Being declared a saint (justification) and becoming more like Christ (sanctification) are inseparably connected in God’s redemptive plan. As Romans 6:1-2 asks, “Shall we go on sinning so that grace may increase? By no means!” The Reformed view emphasises that while our sainthood is secure in Christ, the Holy Spirit works within us to make our practice increasingly match our position. Our struggle against sin is evidence of our new nature in Christ, not a means of earning our standing before God.

- Do some Christian traditions teach that believers can achieve sinless perfection in this life? Yes, some Wesleyan and Holiness traditions have historically taught Christians can attain a state of “entire sanctification” or “Christian perfection” in this life. The Reformed position, however, maintains that while the power of sin is broken at conversion, its presence remains until glorification. First John 1:8 states clearly, “If we claim to be without sin, we deceive ourselves and the truth is not in us,” which Reformed theology takes as evidence that sinless perfection is not attainable this side of heaven.

How can I know if I’m truly a “saint” if I still struggle with the same sins? Assurance in Reformed theology is based on Christ’s finished work, not on our performance. The very fact we struggle against sin rather than comfortably embracing it suggests the Holy Spirit’s work in us. As Romans 7-8 demonstrates, the believer’s experience is characterised by an ongoing battle against sin, coupled with a profound confidence in Christ’s redemptive work. Our awareness of sin and desire for holiness are actually signs of spiritual life, not reasons to doubt our standing as a saint.

- If God sees me as righteous in Christ, does He still see my sin? God’s knowledge is perfect and comprehensive—He certainly sees our sin, but He chooses not to count it against us if we’re in Christ. The Reformed distinction between God’s omniscience (knowing all things) and His judicial declaration (not counting sin against believers) helps explain the tension. When God the Father looks at believers, He sees both their sin and the perfect righteousness of Christ that covers them, and He relates to them based on the latter.

- What about the “mortal sin” concept—can a true saint commit sins that threaten their salvation? Some traditions distinguish between “venial” and “mortal” sins, with the latter potentially causing loss of salvation. Reformed theology, however, emphasises the perseverance of saints—those truly regenerated by the Holy Spirit will persevere in faith to the end. While sin always brings consequences and can damage our fellowship with God, it cannot sever the believer’s union with Christ. As Romans 8:38-39 declares, nothing can separate us from God’s love in Christ Jesus—a truth that provides profound assurance while simultaneously calling us to holy living.

If I’m already positionally holy as a saint, why do I need more forgiveness when I sin? The Reformed distinction between judicial forgiveness (justification) and parental forgiveness (ongoing relationship) helps clarify this question. When we trust in Christ, we receive once-for-all judicial forgiveness that secures our eternal standing before God. However, as children in God’s family, our daily sins still affect our fellowship with Him and our joy, requiring ongoing confession and restoration. First John 1:9 instructs believers to confess their sins to maintain close communion with God, even though their ultimate standing as saints remains secure.

SAINTS AND SINNERS: OUR RELATED POSTS

Editor's Pick

The Throne-Room Vision: Who Did Isaiah See?

The scene is unforgettable: Isaiah stands in the temple, and suddenly the veil between heaven and earth tears open. He [...]

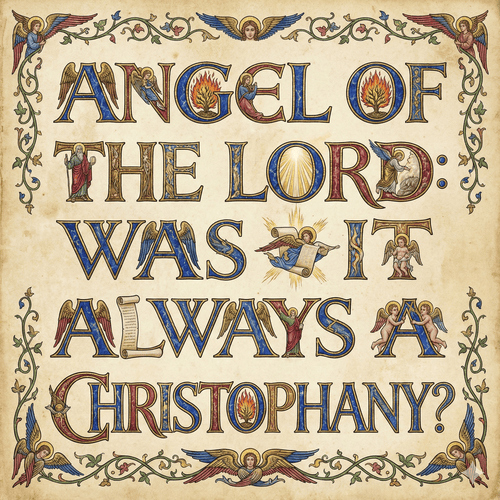

The Angel of the Lord: Can We Be Certain It Was Christ All Along?

Throughout the Old Testament, a mysterious figure appears: the Angel of the LORD. He speaks as God, bears God’s name, [...]

SUPPORT US:

Feel the Holy Spirit's gentle nudge to partner with us?

Donate Online:

Account Name: TRUTHS TO DIE FOR FOUNDATION

Account Number: 10243565459

Bank IFSC: IDFB0043391

Bank Name: IDFC FIRST BANK