Son of God: What Did This Title Mean to Jews in Jesus’ Day?

When Jesus was called the “Son of God”—or when He claimed this title for Himself—what did this actually mean to Jewish ears in the first century? For modern Christians, this title immediately signifies Jesus’ divinity and His place in the Trinity. But what did it mean within its original Jewish context?

Understanding this question is crucial for grasping the full significance of Jesus’ identity and mission. Let’s explore what “Son of God” would have conveyed to Jews of Jesus’ time, through the lens of Reformed theology.

JEWISH BACKGROUND OF DIVINE SONSHIP

In the Hebrew Scriptures, “son of God” wasn’t exclusively a divine title. It appeared in several significant contexts:

- Israel as God’s Son: God referred to the entire nation of Israel as “my firstborn son” (Exodus 4:22-23). The prophet Hosea echoed this: “Out of Egypt I called my son” (Hosea 11:1). This sonship reflected Israel’s covenant relationship with God.

- Angels as “Sons of God”: Heavenly beings were sometimes described as “sons of God” (Job 1:6, 38:7), marking their creation by and service to God.

- The Davidic King as God’s Son: Most relevant to Jesus, God promised David: “I will be to him a father, and he shall be to me a son” (2 Samuel 7:14). Similarly, Psalm 2:7 declares to the king: “You are my Son; today I have begotten you.”

By the time of Jesus, Jewish thinking had developed further. During the intertestamental period, there emerged a growing reluctance to use familial language for God, considering it too intimate for the transcendent Creator. Yet messianic expectations often incorporated the idea of a coming king who would have a special relationship with God, potentially as His “son” in a meaningful sense.

JESUS’ SELF-UNDERSTANDING AS SON

Jesus’ own usage of “Son” language was revolutionary. He spoke of God as “my Father” with striking intimacy, using the Aramaic term “Abba”—a familiar, personal form of address that shocked many of His hearers.

In the parable of the wicked tenants (Mark 12:1-12), Jesus distinguished Himself from the prophets as the “beloved son” of the vineyard owner—a thinly veiled reference to His unique relationship with God the Father.

Perhaps most boldly, Jesus claimed: “All things have been handed over to me by my Father, and no one knows the Son except the Father, and no one knows the Father except the Son and anyone to whom the Son chooses to reveal him” (Matthew 11:27). This statement suggests a mutual, exclusive knowledge between Father and Son that transcends typical human-divine relationships.

JEWISH REACTIONS TO JESUS’ “SON OF GOD” CLAIMS

These claims received mixed reactions from Jesus’ Jewish contemporaries.

Some understood the title in purely messianic terms—recognising Jesus as God’s specially appointed king in the line of David. This interpretation wasn’t necessarily blasphemous; it aligned with Jewish expectations of a coming deliverer.

Others, however, perceived something far more provocative in Jesus’ claims. In John 5:18, the Jewish leaders sought to kill Jesus because “he was even calling God his own Father, making himself equal with God.” Later, they declared: “It is not for a good work that we are going to stone you but for blasphemy, because you, being a man, make yourself God” (John 10:33).

This reaction reveals a crucial insight: Jesus wasn’t merely claiming to be God’s son in the traditional Jewish sense of a righteous person or chosen king. Something in His words and actions suggested a unique, divine identity that some Jews found revolutionary and others found blasphemous.

THE UNIQUENESS OF JESUS’ SONSHIP

Reformed theology highlights Jesus’ sonship as transcending, yet incorporating earlier Jewish conceptions. Jesus isn’t merely:

- A son of God by creation (like angels)

- A son of God by adoption (like Israel)

- A son of God by appointment (like the Davidic king)

Rather, He is the eternal Son of God—the second person of the Trinity who has always existed in perfect communion with the Father. As the Nicene Creed would later affirm, He is “begotten, not made, being of one substance with the Father.”

This eternal sonship explains why Jesus could make such extraordinary claims about His relationship with God without contradicting Jewish monotheism. He wasn’t claiming to be a second god but revealing the complex nature of the one true God.

The Reformed tradition emphasises Christ’s sonship is both ontological (relating to His being) and functional (relating to His role in salvation). As the Son, Jesus perfectly reveals the Father (John 14:9) and accomplishes the Father’s will in creation and redemption.

CONCLUSION: SON OF GOD

For Jews in Jesus’ day, “Son of God” carried a rich tapestry of meanings—from national identity to messianic expectation. Jesus took this familiar title and filled it with radical new meaning, revealing Himself to be not just another anointed human king but the eternal Son who had always existed in perfect communion with the Father.

This understanding doesn’t abandon Jewish monotheism but deepens it, revealing the rich complexity of God’s nature. We confess with the church throughout the ages that Jesus Christ is “the only-begotten Son of God, begotten of the Father before all worlds, God of God, Light of Light, very God of very God.”

In Jesus, we meet not just a son of God, but the Son of God—the One who perfectly reveals the Father and reconciles us to Him. This is the heart of our faith and the foundation of our hope.

SON OF GOD: RELATED FAQs

Did other messianic figures in Jewish history claim to be the “Son of God”? While several messianic claimants arose in first-century Judaism, none made the unique filial claims Jesus did about His relationship with the Father. Unlike Jesus, figures like Theudas or the Egyptian prophet mentioned in Acts made claims of prophetic authority or military deliverance but did not claim divine sonship in the intimate sense Jesus portrayed. This uniqueness highlights the unprecedented nature of Jesus’ ministry and self-understanding.

How did the early church reconcile Jesus as “Son of God” with strict Jewish monotheism? The early church maintained strict monotheism while expanding its understanding of God’s nature through Jesus’ revelation. Rather than abandoning the Shema (Deuteronomy 6:4), early believers reconceived it through the lens of Jesus’ unique relationship with the Father, developing what would later become Trinitarian theology. This delicate balance between affirming one God while recognizing Jesus’ divinity reflects the Reformed principle that later doctrinal developments clarify rather than contradict Scripture’s teachings.

What’s the difference between Jesus as the “Son of God” and believers as “sons of God”? Jesus is the eternal, natural, and only-begotten Son, sharing the divine nature and existing in eternal relationship with the Father. Believers, by contrast, become God’s sons and daughters through adoption, receiving this status as a gift of grace through our union with Christ. The Reformed tradition emphasises this distinction while celebrating that our adoption is real and grants genuine privileges as heirs with Christ.

Did the title “Son of God” have political implications in the Roman world? In the Roman Empire, emperors claimed divine sonship and even used the title “son of god” (divi filius) in imperial propaganda. Jesus’ claim to this title therefore carried potentially subversive political implications, suggesting allegiance to a kingdom and King above Caesar. Reformed theology has historically emphasised Christ’s lordship over all spheres, including the political, while maintaining that His kingdom operates differently from worldly powers.

How does Jesus’ sonship relate to covenant theology in the Reformed tradition? In Reformed covenant theology, Jesus as the eternal Son is the mediator of both the covenant of works (which Adam failed to keep) and the covenant of grace. His filial relationship with the Father is the foundation for our covenant relationship with God, as we are brought into God’s family through union with the Son. This covenantal framework helps us understand how God relates to His people throughout redemptive history with the Son always at the centre.

Would first-century Jews have connected the “Son of God” title with pre-existence? Most first-century Jewish conceptions of the Messiah did not include pre-existence, viewing the “Son of God” as a human figure specially chosen by God. Jesus’ claims about His relationship with the Father before creation (John 17:5) therefore represented a significant theological development beyond common messianic expectations. Reformed theology affirms Christ’s pre-existence as essential to His nature as the eternal Son, not merely a role He assumed at some point in time.

How does the Holy Spirit relate to Jesus’ identity as “Son of God”? The Holy Spirit plays a crucial role in testifying to and manifesting Jesus’ divine sonship, particularly at His baptism when the Spirit descended while the Father declared, “This is my beloved Son.” Reformed theology sees the Spirit’s work as essential in both revealing Christ’s sonship to believers and enabling our adoption as God’s children through union with the Son. This Trinitarian perspective enriches our understanding of how the three persons work together in perfect harmony.

SON OF GOD: OUR RELATED POSTS

Editor's Pick

Will We Remember This Life in Heaven? What Isaiah 65:17 Means

"Will I remember my spouse in heaven? My children? Will the joy we shared on earth matter in eternity?" These [...]

From Empty to Overflow: The Abundant Life Jesus Promised

(AND WHY YOU SHOULDN’T SETTLE FOR LESS) We're surviving, but are we thriving? If we're honest, there's a gap between [...]

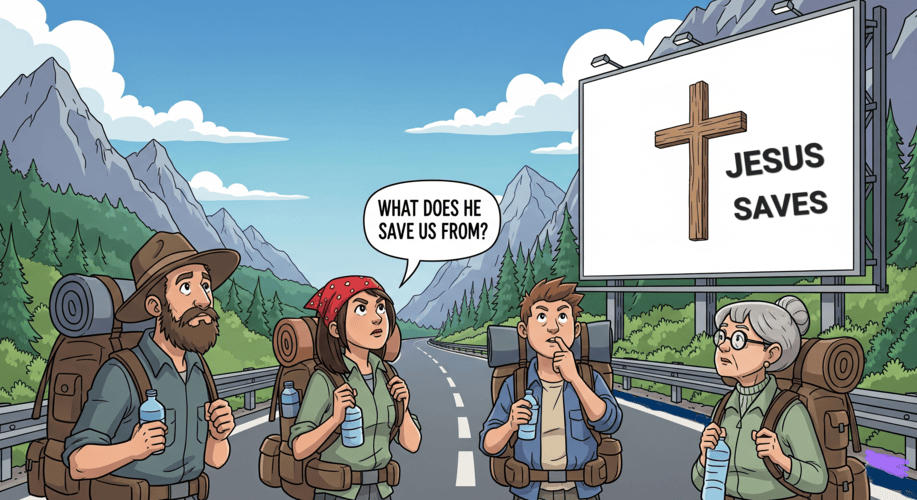

What Does Jesus Save Us From?

THREE BIBLE TRUTHS ABOUT SALVATION "Jesus saves." We’ve seen it on bumper stickers, heard it shouted at sporting events, maybe [...]

If God Wants Everyone Saved, Why Aren’t They?

THE REFORMED VIEW ON GOD’S DESIRE VS HIS DECREE The question haunts every believer who has lost an unbelieving loved [...]

The One Man Mystery in Acts 17:26: Is It Adam Or Noah?

When the Apostle Paul stood before the philosophers at Mars Hill, he delivered an insightful statement about human unity: “And [...]

Megiddo Or Jerusalem: Where Did King Josiah Die?

Recent archaeological discoveries at Tel Megiddo continue to reveal evidence of Egyptian military presence during the late 7th century BC, [...]

Losing Your Life Vs Wasting It: How Are the Two Different?

AND WHY DID JESUS PRAISE THE FORMER? Jesus spoke one of the most perplexing statements in Scripture: “For whoever wants [...]

Can Christians Be Demon Possessed? What the Bible Teaches

Perhaps you’ve witnessed disturbing behavior in a professing Christian, or you’ve struggled with persistent sin and wondered if something darker [...]

Sacred Fury: What Christ’s Temple Cleansing Truly Means

Mark 11 records the crack of a handmade whip that echoed through the temple corridors. Tables crashed to the ground, [...]

Did Jesus Cleanse the Temple Twice?

OR DID JOHN DISAGREE WITH THE SYNOPTICS ON TIMING? One of sceptics’ favourite "gotcha" questions targets what they see as [...]

SUPPORT US:

Feel the Holy Spirit's gentle nudge to partner with us?

Donate Online:

Account Name: TRUTHS TO DIE FOR FOUNDATION

Account Number: 10243565459

Bank IFSC: IDFB0043391

Bank Name: IDFC FIRST BANK