The Case for Sola Scriptura: Can We Trust the Reformers?

“If the Reformers were just fallible men, why should we trust their doctrine of Sola Scriptura—the teaching that Scripture alone is our final authority?”

It’s a fair question—one that deserves a serious answer. After all, Luther, Calvin, and the other Reformers weren’t apostles. They made mistakes, disagreed with each other, and held positions we might question today. So why should their recovery of Sola Scriptura carry any weight?

Here’s the critical point: The Reformers never asked us to trust them. They pointed us to Scripture alone as our infallible authority. Their fallibility doesn’t weaken the case for Sola Scriptura—it strengthens it, because they subjected themselves to the very authority they proclaimed.

THE REFORMERS CLAIMED NO AUTHORITY FOR THEMSELVES

Unlike Rome’s claims for papal infallibility, the Reformers explicitly acknowledged their fallibility and subordinated all human authority to Scripture.

When Martin Luther stood before the Diet of Worms in 1521, facing excommunication and probable execution, he didn’t appeal to his own authority or insight. Instead, he declared: “Unless I am convinced by Scripture and plain reason—for I do not accept the authority of popes and councils, for they have contradicted each other—my conscience is captive to the Word of God. I cannot and will not recant anything, for to go against conscience is neither right nor safe.”

Notice what Luther did: He placed Scripture above himself, above the Pope, above church councils. He invited correction—but only from God’s Word.

Calvin echoed this principle throughout his Institutes. In Book 1, Chapter 7, he argued Scripture is “self-authenticated” (autopiston), carrying its own divine authority, and obviating the need for any human approval. We don’t believe Scripture because the church says so; the church recognises Scripture because God speaks through it.

The Westminster Confession makes this crystal clear: “The supreme judge by which all controversies of religion are to be determined… can be no other but the Holy Spirit speaking in the Scripture” (WCF 1.10). Not the Reformers. Not tradition. Scripture alone.

Francis Turretin, the great Reformed scholastic, carefully distinguished between the divine authority of Scripture and the fallible ministry of the church. The church can point to Scripture, translate it, and teach it—but it cannot add to it or override it.

This is the opposite of claiming personal authority. The Reformers invited constant correction from Scripture. That’s precisely what Sola Scriptura means.

SCRIPTURE TEACHES ITS OWN SUFFICIENCY

The Reformers didn’t invent this doctrine—they recovered it from texts in the Bible.

Paul told Timothy “All Scripture is God-breathed and is useful for teaching, rebuking, correcting and training in righteousness, so that the servant of God may be thoroughly equipped for every good work” (2 Timothy 3:16-17). If Scripture thoroughly equips us for every good work, what else do we need?

The Bereans were commended as “noble” because they “examined the Scriptures every day to see if what Paul said was true” (Acts 17:11). Think about that: They tested even apostolic teaching against Scripture. If the apostles themselves were subject to scriptural verification, how much more are fallible Reformers—or popes, or councils?

Isaiah declared, “To the law and to the testimony! If they do not speak according to this word, they have no light of dawn” (Isaiah 8:20). Jesus rebuked the Pharisees for “nullifying the word of God for the sake of your tradition” (Matthew 15:6). And Paul pronounced a curse on anyone—even “an angel from heaven”—who would preach a gospel contrary to Scripture (Galatians 1:8-9).

If angels and apostles are accountable to Scripture, no human tradition can claim exemption. The Reformers simply took these texts seriously and applied them consistently. They were faithful witnesses to what Scripture already taught about itself, not authoritative innovators.

ISNT IT CIRCULAR REASONING TO USE SCRIPTURE TO DEFEND SOLA SCRIPTURA?

This is a sophisticated objection to Sola Scriptura, but Reformed epistemologists like Cornelius Van Til and John Frame argue all ultimate authorities are self-attesting by nature—they can’t appeal to something higher without ceasing to be ultimate. Catholics face the same issue: they must ultimately appeal to the Church’s authority to validate the Church’s authority. The question isn’t whether circularity exists at the foundational level, but which circle is vicious and which is virtuous. Reformed scholar James Anderson points out Scripture’s self-authentication isn’t arbitrarily asserted but demonstrated through its internal coherence, prophetic fulfilment, transformative power, and the Spirit’s testimony in believers’ hearts. The real issue is whether our ultimate authority is God speaking (Scripture) or humans claiming to speak for God (magisterium).

HISTORY PROVES SCRIPTURE CORRECTS FALLIBLE MEN

The pattern of Scripture correcting even faithful theologians validates the entire principle of Sola Scriptura.

Augustine, the great North African bishop, held views on predestination that later theologians refined through careful study of Romans 9-11. Early church fathers disagreed on which books belonged in the canon until Scripture’s self-authenticating nature settled the matter. Even the Reformers themselves disagreed sharply—Luther and Zwingli famously parted ways over the Lord’s Supper.

These disagreements prove the point: No one claimed infallibility. Every generation must return ad fontes—to the sources—examining all tradition by the standard of Scripture. As the Heidelberg Catechism teaches, good works must flow “from true faith, according to the law of God, and to His glory” (Q&A 91). Scripture, not human opinion, defines what honours God.

This is precisely how Sola Scriptura functions. We don’t trust men; we trust the Word that judges all men (Hebrews 4:12).

THEIR MARTYRDOM VALIDATES THEIR SINCERITY

Consider what the Reformers risked. Luther faced excommunication and lived under threat of execution. William Tyndale was strangled and burned at the stake for translating Scripture into English. Countless others were imprisoned, exiled, or killed for insisting Scripture alone was supreme.

Here’s the remarkable thing: If the Reformers merely sought power or wanted people to trust them, they’d have claimed infallibility like Rome did. Instead, they proclaimed a principle that diminished every human authority and subjected them to divine judgement. They chose persecution over papal privilege.

As Turretin put it, “We do not fight for our own traditions but for the Word of God alone.”

TRUST SCRIPTURE, NOT MEN

So can we trust the Reformers on Sola Scriptura? We don’t have to—and they wouldn’t want us to. They pointed beyond themselves to the infallible Word of God. Test their teaching by Scripture, just as they invited their own generation to do.

The Reformers were fallible men who recognised an infallible authority. That’s not a weakness of their position; it’s the whole point. We trust Sola Scriptura not despite the Reformers’ fallibility, but because they knew they were fallible—and bowed before Scripture accordingly.

RELATED FAQs

Didn’t the Reformers disagree on what books belong in the Bible? Luther famously questioned James, calling it an “epistle of straw,” and had concerns about Hebrews, Jude, and Revelation. However, he never removed these books from his Bible—he simply placed them in an appendix with a note about their disputed status in early church history. This actually demonstrates Sola Scriptura at work: Luther subjected his own opinions to the church’s historical judgement about the canon. Modern Reformed scholars like Michael Kruger argue the canon is self-authenticating through the Spirit’s witness, not dependent on any individual’s opinion—even a Reformer’s.

- How do Reformed scholars today defend Sola Scriptura against Catholic arguments? Theologians like Keith Mathison (in The Shape of Sola Scriptura) and James White distinguish between solo scriptura (individualistic “me and my Bible”) and genuine sola scriptura (Scripture as supreme authority within the community of faith). They argue Sola Scriptura doesn’t reject tradition or the church’s teaching role—it subjects them to Scripture’s corrective authority. Kevin Vanhoozer has developed a “canonical-linguistic” approach, showing how Scripture provides the authoritative “script” for the church’s ongoing drama, while pastors and theologians serve as faithful “performers” rather than co-authors.

- If everyone interprets Scripture differently, doesn’t that prove we need an infallible interpreter like the Pope? Reformed theologian RC Sproul addressed this by noting that Catholics face the same problem: Who infallibly interprets the Pope’s infallible statements? The problem of interpretation exists at every level. The real question is whether our final authority is inherently infallible (Scripture) or merely claimed to be infallible (papal pronouncements). Moreover, the fact that Christians throughout history have agreed on core doctrines (the Trinity, the Incarnation, justification by faith) using Scripture alone demonstrates the Bible is sufficiently clear on essential matters—what the Reformers called the “perspicuity” of Scripture.

What about 2 Thessalonians 2:15, where Paul tells believers to hold to “traditions” whether written or oral? This is a common Catholic objection, but Reformed scholars point out Paul is writing to first-generation Christians who had direct access to apostolic teaching. Carl Trueman and others note Paul elsewhere commanded the Thessalonians to test everything (1 Thessalonians 5:21) and that no apostolic “oral tradition” contradicts the written Scripture we possess. Once the apostolic era ended and Scripture was complete, the written Word became the sole infallible repository of apostolic teaching—this is why Jude urged believers to “contend for the faith that was once for all entrusted to God’s holy people” (Jude 3, emphasis added).

- How did the Reformers know which church fathers to trust if they rejected church authority? The Reformers didn’t reject the fathers—they read them extensively and cited them constantly. Calvin’s Institutes is filled with references to the church fathers, and the Reformers saw themselves as recovering the fathers’ own biblical principles. However, they applied a consistent test: When fathers agreed with Scripture, they were valuable witnesses; when they contradicted Scripture, they were corrected by it. As theologian Alister McGrath notes, the Reformers practiced “critical retrieval”—learning from tradition while remaining free to critique it by biblical standards. This is very different from viewing tradition as an independent authority alongside Scripture.

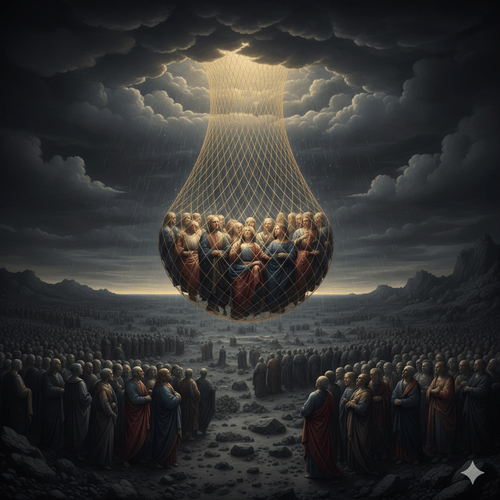

- Didn’t the Catholic Church give us the Bible? So shouldn’t we trust the Church’s authority over it? Modern Reformed apologists like James White respond this confuses the church’s ministerial role with magisterial authority. The church recognised and preserved the canon, but it didn’t create or authorise Scripture’s divine authority—God did. It’s like saying the mailman who delivers a letter from the President has authority over the President’s words. Scholars like Michael Kruger argue the canonical books were self-authenticating through internal qualities (apostolic origin, doctrinal consistency, widespread early acceptance) that the church recognised rather than conferred. The church is the witness to Scripture, not its judge.

What about practical issues like church governance that Scripture doesn’t explicitly address? Reformed theologian John Frame distinguishes between Scripture’s explicit commands (regulative principle) and areas of Christian liberty where wisdom principles apply. Westminster Confession 1.6 acknowledges “there are some circumstances concerning the worship of God and government of the church… which are to be ordered by the light of nature and Christian prudence, according to the general rules of the Word.” This means Scripture provides sufficient principles even when it doesn’t give exhaustive details. Writers like Kevin DeYoung emphasise Sola Scriptura means Scripture is our supreme and sufficient rule, not that it addresses every conceivable question with the same level of specificity—we apply biblical wisdom to new situations under Scripture’s authority.

OUR RELATED POSTS

Editor's Pick

Why Do People Hate the Doctrine of Election?

…WHEN THEY REALLY SHOULDN’T Few Bible doctrines provoke stronger reactions than election. The idea that God chose some for salvation [...]

The Doctrine of Providence: Does God Really Govern All Things?

You’re sitting in the doctor’s office when the diagnosis lands like a thunderclap. Your mind races: Why this? Why now? [...]

No Decay, No Defeat: What It Means That Christ’s Body Saw No Corruption

On the Day of Pentecost, Peter stood before thousands and made a startling claim: David's body decayed in the tomb, [...]

SUPPORT US:

Feel the Holy Spirit's gentle nudge to partner with us?

Donate Online:

Account Name: TRUTHS TO DIE FOR FOUNDATION

Account Number: 10243565459

Bank IFSC: IDFB0043391

Bank Name: IDFC FIRST BANK