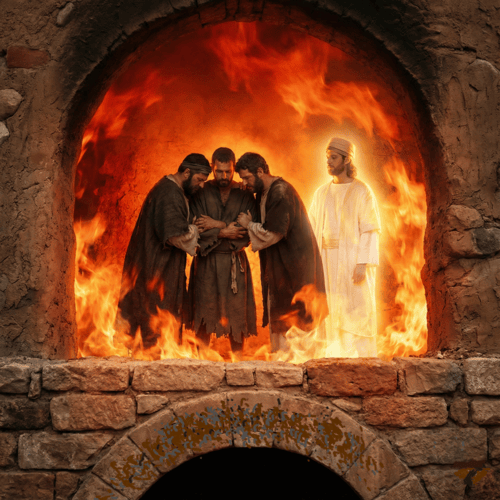

The Fourth Man in the Fire: Was It Really Christ?

WHY REFORMED SCHOLARS EXERCISE CAUTION

The scene is unforgettable: three Hebrew exiles—Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego—stand bound in a furnace heated seven times hotter than usual, flames licking at the edges of their faith. King Nebuchadnezzar peers into the inferno and gasps. He sees not three men, but four. And the fourth, he declares, looks “like a son of the gods” (Daniel 3:25).

For centuries, Christians have wondered: Could this mysterious fourth figure be Jesus Christ in a pre-incarnate appearance? The question has sparked passionate debate, inspiring countless sermons and Sunday school lessons.

While the figure is certainly supernatural and sent by Yahweh, the most careful and confessionally Reformed reading identifies him as a high angel—but not the Second Person of the Trinity Himself. This conclusion doesn’t diminish the passage’s power; rather, it honours what the text actually says and preserves crucial theological categories about Christ’s unique incarnation.

WHAT THE TEXT ACTUALLY SAYS

Before we rush to identify the mysterious fourth man, we need to examine what Daniel’s narrative actually tells us—and just as importantly, who is doing the telling.

The description comes from Nebuchadnezzar, a pagan king who moments earlier had demanded the entire province worship his golden image. His observation that the figure appears “like a son of the gods” reflects polytheistic categories. This is the same king who kept a stable of magicians, enchanters, and sorcerers on his royal payroll.

Even more tellingly, Nebuchadnezzar himself later revises his interpretation. In verse 28, he declares: “Blessed be the God of Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego, who has sent his angel and delivered his servants.” The king explicitly identifies the figure as an angel—a messenger sent by the God of Israel.

Nowhere does Daniel, the inspired author writing under the Spirit’s guidance, contradict this angelic identification. We’re given no prophetic commentary suggesting this was something more. The narrative simply records the miraculous deliverance and moves forward.

WHY ARE REFORMED EXEGETES CAUTIOUS?

The Incarnation Is Unique and Unrepeatable

Reformed theology holds tenaciously to the glory of the Incarnation. When John writes “the Word became flesh and dwelt among us” (John 1:14), he’s describing something that happened once, in history, at Bethlehem. The eternal Son of God took on human nature in a union that will never be dissolved.

As Herman Bavinck wisely cautions us in his Reformed Dogmatics: “We may not multiply Christophanies beyond what Scripture clearly warrants.” The concern isn’t mere theological fastidiousness—it’s preserving the scandal and wonder of the Incarnation itself. If Christ regularly appeared in bodily form throughout the Old Testament, what makes His coming in the flesh so revolutionary?

The writer of Hebrews emphasises this decisively: “Long ago, at many times and in many ways, God spoke to our fathers by the prophets, but in these last days he has spoken to us by his Son” (Hebrews 1:1-2). There’s a fundamental before-and-after structure to redemptive history. God worked through prophets, angels, and various means—then He sent His Son. The Incarnation isn’t simply another appearance; it’s the culmination of all God’s prior speaking.

Sound Interpretive Principles Demand Evidence

Reformed hermeneutics insists on a crucial principle: let clear passages interpret unclear ones, and don’t build doctrine on ambiguous texts. While Daniel 3 is vivid and powerful, it’s hardly explicit about the figure’s identity.

Consider the contrast with other Old Testament passages. When Paul wants to identify a Christophany, he does so clearly: “They drank from the spiritual Rock that followed them, and the Rock was Christ” (1 Corinthians 10:4). The New Testament writers had every opportunity to identify the fourth man in Daniel 3 as Christ. They never do.

As Sinclair Ferguson observes: “To identify the fourth figure as Christ Himself is exegetically unnecessary and theologically precarious.” The passage makes complete sense as an account of angelic deliverance—the kind God performs repeatedly throughout Scripture. Angels appear in human form throughout the Bible: to Abraham at Mamre, to Jacob at Peniel, to Gideon under the oak. Why must this be different?

The Text Functions Beautifully as Angelic Ministry

Far from being a theological letdown, recognising this as an angelic deliverance actually enriches our reading. God doesn’t need to personally enter the furnace to demonstrate His power and covenant love. He sends His angel to accomplish His will.

This aligns perfectly with the biblical pattern. God sends angels as His representatives, bearing His authority and presence. Angels serve as God’s ministers, executing His judgements and protecting His people.

The original audience—Jewish exiles in Babylon—would have immediately understood this as divine deliverance through angelic agency. They needed no elaborate Christological explanations. God hadn’t abandoned them. Even in the furnace of persecution, His messenger stood with them.

WHAT WE CAN AFFIRM WITH CONFIDENCE

So what does this passage teach us?

God is present with His people in their suffering. Isaiah’s promise echoes through this narrative: “When you walk through fire you shall not be burned, and the flame shall not consume you” (Isaiah 43:2). Whether through angel or direct intervention, God’s protective presence surrounds those who remain faithful.

Divine power supersedes earthly tyranny. Nebuchadnezzar’s furnace, heated to maximum intensity, becomes the very theatre where God’s supremacy is displayed. The ropes binding the three Hebrews burn away, but not a hair on their heads is singed. The empire’s most fearsome weapon becomes the stage for God’s deliverance.

The pattern points forward to greater fulfillment. God’s faithfulness to these three exiles foreshadows His faithfulness to send His Son into our human condition—into a fire far worse than Nebuchadnezzar’s furnace.

THE GREATER FIRE

If we’re cautious about placing Christ in the Babylonian furnace, it’s because we know where He truly entered the flames. At Calvary, Jesus didn’t accompany sufferers through the fire—He became the offering consumed by it. He bore the furnace of God’s wrath against sin, experiencing the abandonment that Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego never did. “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” No angel stood with Him in that ultimate fire.

This is why Reformed exegetes hesitate to multiply Christophanies unnecessarily. Not because we’re afraid of seeing Christ in the Old Testament, but because we’re jealous to preserve the uniqueness of what He accomplished in the flesh. The fourth man in the fire demonstrates God’s pattern of deliverance. Jesus is that deliverance, embodied, incarnate, crucified, and resurrected.

The passage loses none of its power when we read it carefully. God was faithful then; God is faithful now. Whether He sends an angel or comes Himself, He does not abandon His people. And in the fullness of time, He sent not a messenger but His Son—not to walk through our fires with us, but to be consumed by them in our place.

That’s a fire story worth telling.

RELATED FAQs

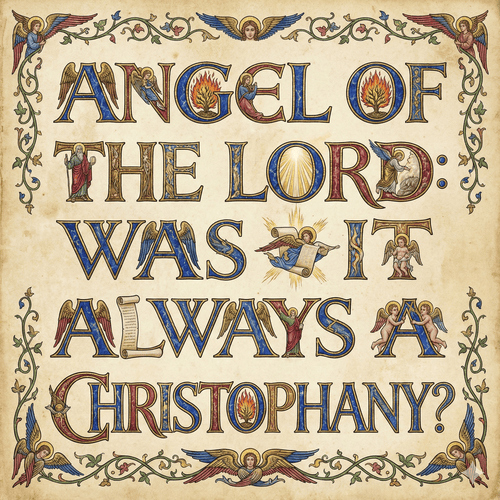

What about the “Angel of the LORD” passages? Aren’t those clearly Christ? The Angel of the LORD appears throughout the Old Testament in ways that blur the line between messenger and deity, speaking as God and bearing the divine name. Many Reformed scholars identify certain appearances—particularly in Genesis 16, Exodus 3, and Judges 13—as pre-incarnate Christophanies where the text explicitly identifies the Angel as YHWH Himself. However, Daniel 3 lacks these distinctive markers: the figure doesn’t speak, doesn’t reveal the divine name, and isn’t identified as YHWH by the inspired author. Even scholars who accept some Angel of the LORD passages as Christophanies typically don’t include Daniel 3 in that category.

- Did the early church fathers think this was Jesus? The evidence is surprisingly mixed. Irenaeus and Tertullian tended to see the figure as the pre-incarnate Son, but their understanding of “appearance” was more flexible than modern evangelical approaches. John Chrysostom explicitly identified the figure as an angel, not Christ, arguing that “like a son of the gods” was Nebuchadnezzar’s pagan way of describing angelic glory. Augustine similarly leaned toward an angelic interpretation, noting verse 28’s identification as “his angel” should guide our reading.

- How do we safely determine whether an angelic appearance is actually a Christophany? Reformed hermeneutics suggests several criteria: First, does the New Testament identify it as such (like Paul identifying the Rock as Christ in 1 Corinthians 10:4)? Second, does the figure speak and act as YHWH Himself, using the divine name or being directly identified with God by the inspired author? Third, is there explicit mediatorial activity involving covenant-making or redemptive promises? GK Beale argues we should generally prefer angelic interpretations unless the text compels us otherwise—not from scepticism, but from humility before Scripture and respect for the Incarnation’s uniqueness.

What did John Calvin himself believe about this passage? Calvin explicitly argues against identifying the fourth figure as Christ, calling such interpretations “too refined” and lacking textual support. He emphasises Nebuchadnezzar was speaking from pagan categories and that verse 28’s identification as “an angel” should settle the matter. For Calvin, the passage teaches God’s providential care through angelic ministry—the miracle itself demonstrates divine power without requiring Christ’s literal presence. This restraint has characterised much Reformed interpretation since, with commentators like Matthew Henry similarly identifying the figure as an angel.

- Doesn’t calling him “like a son of the gods” suggest deity? In Aramaic, “son of the gods” (bar-elahin) doesn’t carry the specific messianic connotations that “Son of God” has in Christian theology—it’s a Semitic idiom meaning “having the nature of” or “belonging to the category of.” Nebuchadnezzar uses similar language in Daniel 4:8-9, calling Daniel a man “in whom is the spirit of the holy gods,” which doesn’t make Daniel divine. Angels are elsewhere called “sons of God” in Scripture (Job 1:6, 38:7), indicating heavenly origin or supernatural nature rather than deity itself.

- What’s at stake theologically if we get this wrong? If we too readily identify Old Testament figures as pre-incarnate Christ, we risk undermining the once-for-all character of the Incarnation—it becomes one appearance among many rather than God’s decisive entry into human nature. There’s also a hermeneutical concern: without clear textual warrant, we can fall into “Christological eisegesis,” finding Christ wherever we want rather than where Scripture actually places Him. Conversely, careful restraint doesn’t diminish Christ—as Graeme Goldsworthy argues, the Old Testament powerfully points forward to Christ through pattern and promise without requiring His literal presence in every supernatural event.

How should this affect how we preach or teach Daniel 3? This passage remains incredibly powerful for proclamation by emphasising what the text clearly teaches: God’s presence with His people in suffering, His power to deliver, and the cost of faithful witness. Use typology carefully—the furnace can foreshadow the greater fire Jesus endured without claiming Christ was literally present in Babylon. Model interpretive humility by admitting uncertainty where the text is unclear, which teaches congregations to distinguish between what Scripture clearly says and what we might wish it said. As Bryan Chapell notes, Christ-centred preaching doesn’t require finding Jesus in every verse, but showing how every text fits into the grand narrative that culminates in Him—which Daniel 3 does beautifully, whether the fourth man is an angel or not.

OUR RELATED POSTS

Editor's Pick

The Throne-Room Vision: Who Did Isaiah See?

The scene is unforgettable: Isaiah stands in the temple, and suddenly the veil between heaven and earth tears open. He [...]

The Angel of the Lord: Can We Be Certain It Was Christ All Along?

Throughout the Old Testament, a mysterious figure appears: the Angel of the LORD. He speaks as God, bears God’s name, [...]

SUPPORT US:

Feel the Holy Spirit's gentle nudge to partner with us?

Donate Online:

Account Name: TRUTHS TO DIE FOR FOUNDATION

Account Number: 10243565459

Bank IFSC: IDFB0043391

Bank Name: IDFC FIRST BANK