The Synoptic Problem: More of a Puzzle than a Problem

The Bible contains four gospels that tell the story of Jesus Christ, but three of them—Matthew, Mark, and Luke—share striking similarities in content, structure, and even specific wording. The three are called the Synoptic Gospels (from the Greek word meaning “seeing together”) because they present a similar view of Jesus’ life and ministry. Yet despite their similarities, they also contain notable differences. This creates what scholars call “the Synoptic Problem”—a fascinating literary and historical puzzle that continues to intrigue biblical scholars and casual readers alike.

WHY MATTHEW, MARK, AND LUKE LOOK ALIKE (BUT AREN’T)

If you’ve ever read through the first three gospels, you may have noticed how similar they can be. For example, all three include the story of Jesus calming a storm on the Sea of Galilee, often using identical phrases. In Matthew 8:26, Mark 4:39, and Luke 8:24, Jesus commands the winds and waves using nearly the same words.

Yet alongside these similarities are distinct differences:

- Mark is the shortest gospel, with a fast-paced, action-oriented narrative.

- Matthew includes extensive teachings of Jesus (like the Sermon on the Mount) not found in Mark.

- Luke features unique parables (like the Good Samaritan) and emphasises Jesus’ interactions with women and outcasts.

These similarities and differences aren’t random—they suggest some kind of literary relationship between the texts. But what exactly is that relationship? That’s the heart of the Synoptic Problem.

THE SYNOPTIC PROBLEM EXPLAINED

Simply put, the Synoptic Problem asks: How do we explain the patterns of agreement and disagreement between Matthew, Mark, and Luke? Did one gospel writer copy from another? Did they all draw from an earlier source? Or did they write independently?

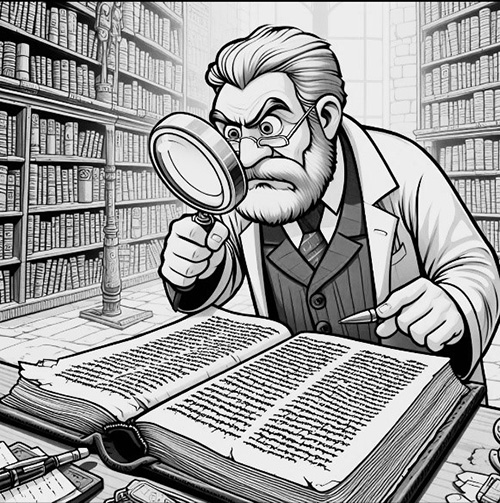

The question emerged as scholars began studying the gospels more carefully during the Enlightenment period. By comparing passages side by side (called a “synopsis”), they noticed intricate patterns of verbal agreement and divergence that couldn’t be explained by mere coincidence.

THE FOUR MAJOR HYPOTHESES

Over centuries of study, scholars have proposed various solutions to this puzzle. Here are the four major hypotheses:

The Markan Priority Hypothesis (Two-Source Theory)

This widely accepted theory proposes that:

- Mark was written first

- Matthew and Luke independently used Mark as a source

- Matthew and Luke also drew from another source (called “Q”) containing sayings of Jesus

- Both added their own unique material

The strengths of this theory include its ability to explain why Mark contains little material not found in either Matthew or Luke, and why Matthew and Luke rarely agree with Mark in their ordering of stories.

The Augustinian Hypothesis

Named after Augustine of Hippo who suggested it in the 5th century, this traditional view proposes:

- Matthew wrote first

- Mark abbreviated Matthew

- Luke used both Matthew and Mark

This hypothesis aligns with early church traditions about gospel authorship and explains why Mark contains mostly material found in Matthew. However, it struggles to explain why Mark would omit important teachings from Matthew or why Luke would rearrange material if he had Matthew’s order in front of him.

The Griesbach Hypothesis (Two-Gospel Hypothesis)

Proposed by Johann Jakob Griesbach in 1789, this theory suggests:

- Matthew wrote first

- Luke used Matthew

- Mark used both Matthew and Luke, essentially creating a condensed version of both

This hypothesis explains why Mark contains little unique material and views Mark as resolving conflicts between Matthew and Luke. Critics argue it doesn’t adequately explain why Mark would omit significant teachings or why it sometimes has more detailed accounts than either Matthew or Luke.

The Farrer Hypothesis (Markan Priority without Q)

This theory proposes:

- Mark wrote first

- Matthew used Mark

- Luke used both Mark and Matthew

The key difference from the Two-Source theory is that it eliminates the hypothetical Q document, suggesting instead that Luke simply borrowed the “Q material” directly from Matthew. This simplifies the model by removing a hypothetical document while still explaining the patterns of agreement and disagreement.

MORE OF A ‘PUZZLE’ THAN A ‘PROBLEM’

The term “problem” derives from the academic tradition of framing research questions as “problems” to be solved, not implying it’s troublesome for faith. Reformed scholars often prefer “Synoptic Puzzle” or “Synoptic Question” to avoid negative connotations, viewing the literary relationships as a fascinating window into God’s providential preservation of the gospel through different yet harmonious witnesses. The interrelationships between the gospels ultimately enrich rather than undermine our understanding of Christ’s life and teachings.

WHAT THIS MEANS FOR BIBLE READERS

Understanding these literary relationships enhances our reading of the gospels in several ways:

- It helps explain why certain stories appear in different contexts across the gospels.

- It highlights each gospel’s distinctive emphasis.

- It reveals the early Christian community preserved multiple perspectives on Jesus rather than enforcing a single narrative.

CONCLUSION

The Synoptic Problem reminds us the gospels are both historical documents and carefully crafted literary works. Each writer selected, arranged, and sometimes modified stories about Jesus to communicate particular theological points to specific audiences.

While scholarly consensus currently favours some form of Markan priority, the debate continues. What matters for most readers isn’t settling on a definitive solution but appreciating how these different voices together create a multi-dimensional portrait of Jesus.

The differences between the Synoptic Gospels don’t undermine their reliability; rather, they demonstrate the rich diversity of early Christian testimony about the life, death, and resurrection of Jesus. In preserving multiple accounts, early Christians valued both faithful transmission and diverse perspective—something we can still appreciate today.

THE SYNOPTIC PROBLEM: RELATED FAQs

Which solution to the Synoptic Problem do most Reformed scholars favour? Most Reformed scholars today accept some version of Markan Priority, though with caution regarding the Q hypothesis. Scholars like DA Carson, Douglas Moo, and Michael Kruger generally work within the Two-Source framework while remaining open to modifications. The key Reformed emphasis is that regardless of literary dependence, all gospels remain divinely inspired.

- Does the Synoptic Problem challenge the doctrine of Bible inerrancy? Not at all. Reformed theology affirms God’s inspiration works through human authors with their distinct styles, sources, and purposes. The literary relationships between gospels simply reveal how God providentially used human means to produce Scripture that is fully divine yet expressed through authentic human voices.

- How might the Synoptic Problem affect our understanding of verbal plenary inspiration? Reformed scholars maintain that verbal plenary inspiration (God’s inspiration extending to the very words of Scripture) is compatible with authors using sources. The Holy Spirit guided the selection, adaptation, and arrangement of material while ensuring the final text communicates exactly what God intended. This demonstrates God’s accommodation to human literary conventions rather than undermining inspiration.

If the gospel writers used sources, were they eyewitnesses? Reformed scholars typically affirm traditional authorship while acknowledging source usage. Matthew was likely an eyewitness apostle who also used sources; Mark likely recorded Peter’s eyewitness testimony; Luke explicitly states he investigated sources carefully. God’s sovereignty worked through both direct eyewitness accounts and careful investigation of reliable sources.

- What does the Synoptic Problem teach us about biblical hermeneutics? From a Reformed perspective, the Synoptic Problem reminds us proper interpretation requires understanding both the divine and human dimensions of Scripture. We must consider each gospel writer’s theological emphasis and purpose while remembering all operate within God’s unified redemptive message, demonstrating the principle that Scripture interprets Scripture.

- How does John’s Gospel fit into the Synoptic Problem? John’s Gospel stands apart from the Synoptic Problem with its distinct structure and content. Reformed scholars generally view John as providing a complementary theological perspective, with his explicitly stated purpose of demonstrating Jesus’s deity. The differences between John and the Synoptics showcase how God provided multiple inspired witnesses to Christ’s person and work.

Does the solution to the Synoptic Problem have implications for dating the gospels? Most Reformed scholars date all four gospels before 70 AD, regardless of their position on literary dependence. While accepting Markan priority might suggest Mark wrote first (possibly 50s AD), followed by Matthew and Luke (60s AD), Reformed scholars typically maintain earlier dates than critical scholarship and emphasise the reliable preservation of Jesus’ words and deeds within the apostolic generation.

THE SYNOPTIC PROBLEM: OUR RELATED POSTS

Editor's Pick

The Throne-Room Vision: Who Did Isaiah See?

The scene is unforgettable: Isaiah stands in the temple, and suddenly the veil between heaven and earth tears open. He [...]

The Angel of the Lord: Can We Be Certain It Was Christ All Along?

Throughout the Old Testament, a mysterious figure appears: the Angel of the LORD. He speaks as God, bears God’s name, [...]

SUPPORT US:

Feel the Holy Spirit's gentle nudge to partner with us?

Donate Online:

Account Name: TRUTHS TO DIE FOR FOUNDATION

Account Number: 10243565459

Bank IFSC: IDFB0043391

Bank Name: IDFC FIRST BANK