What Specifically Was the Sin of Ham, Noah’s Son?

The story of the sin of Ham, Noah’s son, recorded in Genesis 9:20-27, has been the subject of much discussion, even misinterpretation through church history. The narrative, though brief, carries significant theological weight and provides crucial lessons about family relationships, honour, and the far-reaching consequences of sin. Through a careful examination of the biblical text let’s seek to better understand the nature of Ham’s transgression and its implications for us today.

THE NATURE OF HAM’S SIN—THE BIBLICAL ACCOUNT

The narrative begins after the flood, with Noah planting a vineyard, becoming intoxicated, and lying uncovered in his tent. The text tells us:

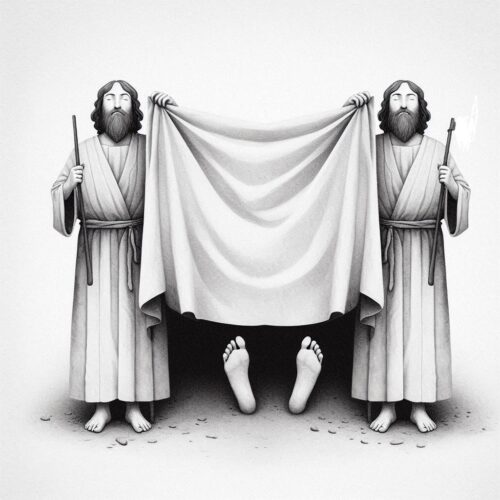

“And Ham, the father of Canaan, saw his father’s nakedness and told his two brothers outside. Then Shem and Japheth took a garment, laid it on both their shoulders, and walked backward and covered the nakedness of their father. Their faces were turned backward, and they did not see their father’s nakedness.”

John Calvin, in his commentary on Genesis, provides crucial insight into the heart of Ham’s transgression: “Ham, by mockingly divulging what he saw, has betrayed his own barbarous pride.” The sin, according to Calvin, wasn’t merely in the seeing—which could have been accidental—but in Ham’s response to what he saw.

Matthew Henry expands on this theme in his famous commentary, noting Ham’s sin represented a triple breach of filial duty:

- First, he failed to turn away from his father’s nakedness, showing no natural reverence.

- Second, he made it a matter of sport and mockery, treating his father’s weakness as entertainment.

- Third, by telling his brothers, he sought to draw others into his sin of dishonouring their father. Henry writes with particular force: “To mock a parent’s infirmity is to turn that into jest which we ought to grieve for… all who make themselves merry with the sins of others are abominably wicked.”

The Act of Gazing: The text’s emphasis on Ham “seeing his father’s nakedness” carries special significance. Francis Turretin and other Reformed commentators note that in Hebrew law and culture, deliberately gazing upon a parent’s nakedness represented a serious violation of family honour. This cultural perspective explains why Moses, the author of Genesis, specifically details Shem and Japheth as walking backwards, so as not to “see their father’s nakedness.” Their careful action is presented as exemplary—in stark contrast to Ham’s behaviour. While Ham chose to look upon his father’s exposed state, his brothers deliberately protected Noah’s dignity by refusing to gaze upon him.

The Element of Mockery: Herman Bavinck points out the Hebrew construction of “told his brothers outside” suggests not merely reporting but gleeful telling. Ham’s action revealed a heart that delighted in his father’s shame rather than seeking to protect his dignity.

SO WHAT SHOULD HAM HAVE DONE INSTEAD?

When we examine the narrative carefully, we discern several proper courses of action that Ham could—and should—have taken upon discovering his father’s vulnerable state. The alternatives illuminate both the gravity of his actual choice and provide wisdom for handling similar situations of vulnerability of family members.

- The Sin Wasn’t in the ‘Seeing’: As Calvin notes in his commentary on Genesis, the initial seeing may well have been accidental. Noah was in his tent: this suggests Ham’s first glimpse of his father’s state wasn’t premeditated. The sin lay not in the initial discovery but in what Ham did thereafter. The right response to an accidental encounter with someone’s vulnerability is to immediately avert one’s eyes—as his brothers later modelled by walking backward.

- Couldn’t Ham Have Covered Noah, Himself? Second, upon discovering his father’s compromised state, Ham had a clear moral obligation to personally and immediately cover Noah. The text presents Shem and Japheth’s actions as exemplary: they took a garment and covered their father. Ham could have done the same, without involving anyone else. This would have fulfilled the basic human duty to protect the dignity of others, particularly a parent.

- Ham Ought to Have Sought Help Differently: If Ham needed help to cover his father, he should have approached his brothers with appropriate gravity and respect. The Hebrew text suggests Ham’s telling was done with a spirit of mockery or levity (“told” carrying connotations of gleeful reporting). Instead, he could have soberly informed his brothers of their father’s need for assistance, focusing on securing help rather than spreading shame.

COMMON MISINTERPRETATIONS

Throughout history, some interpreters have suggested more extreme interpretations of Ham’s sin, including various forms of sexual misconduct. However, Reformed scholars generally reject these interpretations as going beyond what the text actually states. The narrative’s focus is clearly on the dishonour shown to Noah and the contrasting responses of his sons.

CONCLUSION: THE SIN OF HAM, NOAH’S SON

The sin of Ham serves as a warning about the seriousness of dishonouring parents and finding perverse, unholy joy in others’ failures. Yet it also reminds us of God’s grace in working through imperfect families to accomplish His purposes. In Christ, we find both the perfect Son who always honoured His Father and the grace to grow in showing proper honour to our own parents—even when they don’t seem to deserve it.

This incident reminds us we often encounter others, even our parents, in moments of weakness or failure. The godly response isn’t to expose and mock, but to protect and restore with a spirit of gentleness, remembering our own susceptibility to sin (Galatians 6:1).

The lasting lesson is that love covers a multitude of sins (1 Peter 4:8). When we discover the failures of others, particularly within family relationships, our call is to respond with restorative rather than destructive intent. Ham’s sin wasn’t in seeing his father’s weakness, but in delighting in and exposing it. The righteous alternative was—and remains—to cover weakness with love while maintaining appropriate honour.

As we consider this narrative, may we be moved to show greater honour to our parents, greater discretion in our speech, and greater gratitude for Christ’s perfect obedience on our behalf.

THE SIN OF HAM, NOAH’S SON—RELATED FAQs

Was Noah’s drunkenness sinful, and if so, why isn’t he punished? Noah’s drunkenness appears to be culpable—he wasn’t merely drinking wine but became drunk to the point of shameful exposure. However, God’s grace operates even through fallen covenant heads. This incident demonstrates both human responsibility (Noah’s sin) and divine sovereignty (God’s continued use of Noah as covenant representative). The focus of the narrative isn’t on Noah’s sin but on the responding heart attitudes of his sons.

How can Ham be blamed if God sovereignly ordained these events? This narrative beautifully displays the Reformed understanding of compatibility between divine sovereignty and human responsibility. While God sovereignly ordained these events to accomplish His purposes (including the prophetic declaration about the lines of Shem, Ham, and Japheth), Ham acted freely according to his own sinful desires. His mockery flowed from his heart; he wasn’t forced to dishonour his father. As Calvin notes, God’s sovereignty never negates human moral agency.

Why was Canaan cursed instead of Ham directly? The curse on Canaan represents God’s prophetic judgment working through covenantal lines. Noah, speaking prophetically, pronounces judgment not merely on an individual but on a family line that would manifest the same sinful tendencies. This demonstrates how covenant theology understands generational consequences – not as fate but as the natural outworking of spiritual principles within family lines.

Does this story justify any form of racial prejudice? Absolutely not. The curse is covenantal and spiritual, not racial. It specifically concerns Canaan, not all of Ham’s descendants, and is about spiritual disposition rather than ethnicity. Any attempt to use this text to justify racial prejudice represents a serious mishandling of Scripture and violates basic Christian ethics.

How should children respond when they discover their parents’ sins? The contrasting responses of Ham versus Shem and Japheth provide clear guidance. Children should: protect their parents’ dignity rather than expose their failures, and seek restoration rather than humiliation. They should handle knowledge of parental sin discreetly and with mature wisdom, and remember their own fallibility and need for grace.

What are the long-term consequences of dishonouring parents? The narrative suggests attitudes toward authority and family honour tend to reproduce themselves generationally. This doesn’t mean determinism, but rather that children often learn patterns of either honour or dishonour from their parents. The covenant implications remind us that our actions affect not just ourselves but future generations.

Is there hope for families where serious dishonour has occurred? Yes! While the narrative soberly warns about sin’s consequences, it sits within the larger biblical story of God’s redemptive grace. Even where family honour has been breached, the gospel offers hope for repentance, reconciliation, and the breaking of negative patterns through Christ’s transforming work.

How does this story relate to modern issues of social media and privacy? The principles are strikingly relevant. Ham’s sin of gleefully spreading news of his father’s shame parallels modern tendencies to expose others’ failures online. The story warns against using social media to shame family members or delight in others’ failures.

THE SIN OF HAM, NOAH’S SON—OUR RELATED POSTS

Editor's Pick

Paul’s Mandate for Men: Headship Or Servant Leadership? Or Both?

Modern Christianity has fallen into a trap. We've created an either/or battle between "headship" and "servant leadership," as if these [...]

Should We Stop Using Male Pronouns for God? Why Do We Say No?

A friend of ours arrived eagerly at his first theology class in seminary. But he quickly discovered something troubling: the [...]

Did Old Testament Law Force Women to Marry their Rapists?

**Editor’s Note: This post is part of our series, ‘Satan’s Lies: Common Deceptions in the Church Today’… Viral misinformation abounds [...]

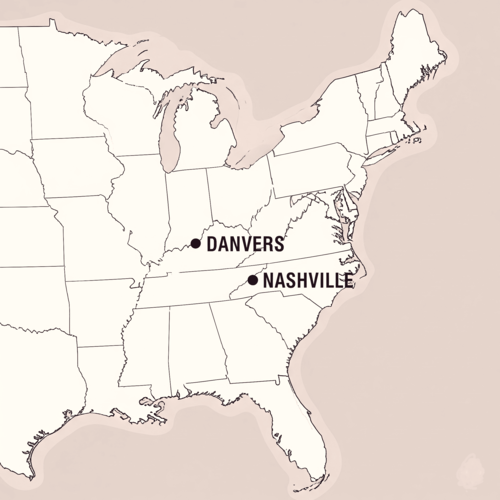

From Danvers To Nashville: Two Statements, One Biblical Vision

30 years separate the Danvers Statement on Biblical Manhood and Womanhood (1987) and the Nashville Statement on Human Sexuality (2017). [...]

The Nashville Statement: Why Affirm It Despite Media Backlash?

WHY DO REFORMED CHRISTIANS STAND BY THIS STATEMENT ON MARRIAGE AND GENDER? When the Nashville Statement was released in 2017, [...]

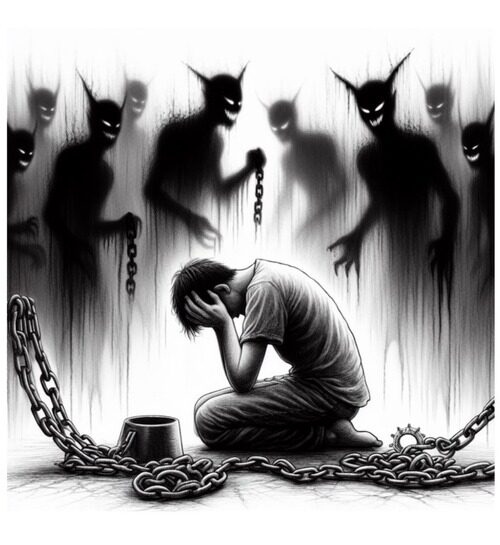

Who Is Belial? Solving The 2 Corinthians 6:15 Mystery

Belial: This name from the pages of Scripture chills the soul. Who is this mysterious figure Paul invokes in 2 [...]

Celibacy Or Castration: What Jesus Really Means in Matthew 19:12

One of Scripture's most shocking misinterpretations led theologian Origen to castrate himself in the third century. His tragic mistake? Taking [...]

Philippians 4:13: Did Paul Really Mean We Can Do ALL Things?

"I can do all things through Christ who strengthens me." It's on gym walls, graduation cards, and motivational posters everywhere. [...]

The Ordinary Means of Grace: Why Are They Indispensable?

ORDINARY MEANS FOR EXTRAORDINARY TRANSFORMATION What if God's most powerful work in believers' lives happens through the most ordinary activities? [...]

Is the Bible God’s Word? Or Does It Only Contain God’s Word?

The authority of Scripture stands at the crossroads of modern Christianity. While some argue the Bible merely contains God’s Word [...]

SUPPORT US:

Feel the Holy Spirit's gentle nudge to partner with us?

Donate Online:

Account Name: TRUTHS TO DIE FOR FOUNDATION

Account Number: 10243565459

Bank IFSC: IDFB0043391

Bank Name: IDFC FIRST BANK