Dating of the Gospels: The Case for Pre-70 AD Authorship

Few questions in biblical scholarship carry as much weight as the dating of the four Gospels. Were Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John written before the destruction of Jerusalem in 70 AD, or after this cataclysmic event? The answer profoundly impacts how we understand these texts—whether as accounts recorded within living memory of Jesus and His disciples or as later theological reflections shaped by decades of distance

While mainstream scholarship has often favoured post-70 AD dating, a compelling case can be made that all four Gospels were composed before Jerusalem fell. Let’s examine the evidence that many scholars find increasingly persuasive.

THE TELLING SILENCE ON JERUSALEM’S DESTRUCTION

Perhaps the most striking evidence for early dating is what the Gospels don’t say. Jesus clearly predicts the destruction of the magnificent Temple in Jerusalem (Mark 13:2). Yet none of the Gospel writers mentions the fulfillment of this prophecy—an omission that defies explanation if they were writing after 70 AD.

Consider the historical context: The Roman destruction of Jerusalem and its Temple was not merely a significant event—it was an earth-shattering catastrophe for first-century Jews. The Temple, the centre of Jewish religious life for centuries, was reduced to rubble. Over a million Jews died in the siege and its aftermath, according to Josephus. Jerusalem, the holy city, lay in ruins.

If the Gospel authors were writing after this event, why wouldn’t they highlight its fulfillment as powerful validation of Jesus’ prophetic authority? The pattern throughout the New Testament is to emphasise fulfilled prophecy—yet this most dramatic fulfillment goes unmentioned.

This silence becomes even more deafening when we note specific details in Jesus’ prophecies that a post-70 writer would likely have emphasised differently. Luke’s account includes specific details about armies surrounding Jerusalem and people fleeing to the mountains, but lacks the specific details of how the destruction actually unfolded—details a post-event writer would most likely have incorporated.

ACTS AS A CHRONOLOGICAL ANCHOR

The Book of Acts provides another compelling timestamp. Written as a sequel to the Gospel of Luke by the same author, Acts ends with Paul under house arrest in Rome, around 62 AD. The narrative stops there, failing to mention:

- Paul’s death (mid-60s AD)

- The martyrdom of James, leader of the Jerusalem church (62 AD)

- The outbreak of the Jewish revolt (66 AD)

- The fall of Jerusalem (70 AD)

This abrupt ending makes little sense if Acts was written after these momentous events. The most straightforward explanation is that Acts was completed around 62-63 AD, before these events occurred.

This creates a domino effect on dating the Gospels:

- Luke must predate Acts

- Luke appears to use Mark as a source, placing Mark earlier still

- Matthew likely shares a timeline similar to Mark’s

- John, while possibly later than the Synoptics, shows no awareness of Jerusalem’s destruction

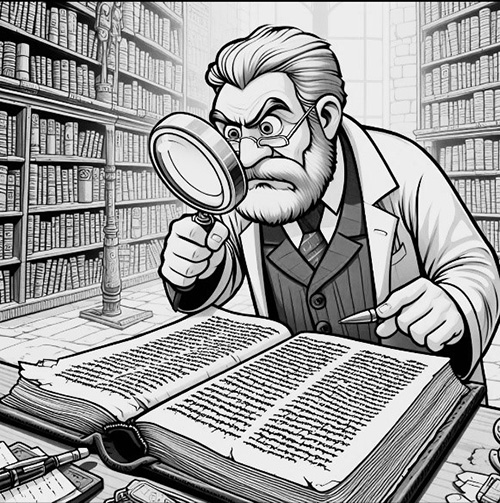

DATING OF THE GOSPELS: TEXTUAL EVIDENCES

The Gospels contain numerous present-tense references to Jerusalem, the Temple, and Jewish customs that would have been anachronistic after 70 AD:

“Jerusalem, Jerusalem… Look, your house is left to you desolate.” (Matthew 23:37-38)

This statement takes on a completely different character if written after the Temple was actually desolate. Yet there’s no indication in the text this has happened.

Similarly, Mark 15:43 mentions Joseph of Arimathea as “a prominent member of the Council, who was himself waiting for the kingdom of God.” The Council (Sanhedrin) ceased to function after 70 AD. Writing about Joseph as a Council member without explanation suggests a pre-70 composition when readers would still recognise this institution.

The Gospels also contain geographical and cultural details subsequently confirmed by archaeology—details that would have been difficult to accurately reconstruct decades later, after Jerusalem’s destruction had fundamentally altered the landscape.

THE LIVING MEMORY FACTOR

The Gospels address audiences who could potentially verify their claims with living witnesses. Luke explicitly appeals to eyewitness testimony in his prologue. Paul, writing in the 50s AD, refers to over 500 witnesses to the resurrection, “most of whom are still living” (1 Corinthians 15:6).

This appeal to living witnesses suggests proximity to the events described—a risky strategy if writing decades later when such verification would no longer be possible.

DATING OF THE GOSPELS: EARLY CHURCH TESTIMONY

External evidence from early Christian writers supports pre-70 dating:

- Papias (early 2nd century) reports that Mark recorded Peter’s teachings, suggesting composition during Peter’s lifetime (before 65-67 AD).

- Irenaeus (late 2nd century) provides a sequence of Gospel composition connected to the apostles’ ministries, not to Jerusalem’s fall.

- Clement of Alexandria reports that the Gospels with genealogies (Matthew and Luke) were written first—a tradition that makes sense only with early dating.

The early manuscript evidence, including fragments like P52 (dated to the early 2nd century), suggests widespread circulation of the Gospels by the early 100s—challenging if they were only composed in the late first century.

ADDRESSING LATER DATING ARGUMENTS

The primary argument for post-70 dating rests on Jesus’ prophecies about the Temple’s destruction. Critics contend these must be “prophecies after the fact.” But this argument assumes the impossibility of genuine prediction—a philosophical position, not a historical conclusion.

The argument also ignores that Jesus’ predictions differ in key ways from the actual events of 70 AD. For instance, his warnings about fleeing to the mountains when Jerusalem is surrounded would have been impractical advice once the Roman siege began.

Some point to theological developments in the Gospels as evidence of later composition. However, recent scholarship has increasingly questioned whether these theological elements actually required decades of development. The high Christology evident in Paul’s letters from the 50s AD demonstrates that core Christian theological concepts emerged very early.

CONCLUSION: DATING OF THE GOSPELS

While dating ancient texts is always complex, the cumulative evidence points toward pre-70 AD composition for the Gospels:

- The silence on Jerusalem’s destruction

- The chronological framework established by Acts

- Present-tense references to pre-70 institutions and locations

- Appeals to living witnesses

- Early church testimony

This evidence suggests we should reconsider the scholarly consensus that has often placed the Gospels later. The simplest explanation for the textual and historical evidence is that Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John were indeed written before Jerusalem fell—accounts composed while the memory of Jesus was still fresh, not distant theological reflections separated by decades from the events they describe.

DATING OF THE GOSPELS: RELATED FAQs

Why does early dating of the Gospels matter? The dating of the Gospels isn’t merely an academic exercise. If the Gospels were written before 70 AD:

- They were composed within the lifetime of eyewitnesses who could correct inaccuracies

- They represent earlier traditions, closer to the events they describe

- They weren’t influenced by the theological crisis of Jerusalem’s destruction

- They contain predictions that hadn’t yet been fulfilled when written

This doesn’t automatically validate every detail in the Gospels, but it does place them in a different historical category—not as late theological reflections but as documents composed when the events they describe were within living memory.

What does Richard Bauckham’s Jesus and the Eyewitnesses contribute to the dating discussion? Bauckham challenges the form-critical model that saw the Gospels as products of anonymous community tradition. Instead, he demonstrates the Gospels contain specific named eyewitnesses who served as authoritative sources and guarantors of the traditions. He analyses the pattern of names in the Gospels, showing how they conform to Palestinian Jewish naming practices of the time rather than later Greco-Roman patterns.

Particularly significant is Bauckham’s observation that the Gospels often include “protective anonymity” for certain figures who were still alive when the accounts were written, suggesting composition during their lifetimes. His work on the “inclusio of eyewitness testimony” identifies literary devices that frame Gospel narratives with references to those who witnessed the entire ministry of Jesus—providing further evidence for composition within living memory of these witnesses.

What unique perspective does John AT Robinson’s Redating the New Testament offer? Robinson’s work is fascinating because he began as a liberal scholar expecting to confirm late dating but found himself driven by evidence to a radical conclusion: that the entire New Testament was written before 70 AD. He argues scholars have been caught in circular reasoning—assuming late dates based on developmental theories, then using those dates to support the same theories.

Robinson meticulously examines linguistic, historical, and theological evidence, noting the New Testament’s silence on the fall of Jerusalem is “the most obvious and striking” feature demanding explanation. He demonstrates that supposed references to events after 70 AD are better explained as predictions or references to other events. Perhaps most compelling is his observation that the New Testament’s descriptions of Jewish-Christian relations reflect a pre-70 reality when the Temple still stood and Christianity was still viewed as a Jewish movement.

How does Colin Hemer’s work on Acts strengthen the case for early Gospel dating? Hemer’s The Book of Acts in the Setting of Hellenistic History offers detailed analysis of the historical accuracy of Acts, documenting over 200 specific details of geography, politics, and culture that Luke got right. This precision on verifiable details strengthens confidence in Luke’s reliability on other matters.

Particularly relevant to dating is Hemer’s demonstration that Acts shows no knowledge of events after 62 AD, including Nero’s persecution, the deaths of Peter, Paul and James, and the Jewish War. He argues that Acts’ abrupt ending with Paul still alive makes sense only if it was written before Paul’s death (mid-60s AD). Since Acts is the sequel to Luke’s Gospel, and Luke appears to use Mark as a source, this pushes Mark’s composition to the early 60s or even 50s AD.

What evidence does Craig Blomberg present about oral tradition and Gospel reliability? In The Historical Reliability of the Gospels, Blomberg addresses a common objection to early dating: the idea that oral tradition would have significantly distorted the Gospel accounts. He demonstrates Jewish educational practices in the first century emphasised accurate memorisation and transmission of a teacher’s words.

Blomberg examines recent studies of oral cultures showing that communities preserve core elements of important stories with remarkable accuracy while allowing flexibility in peripheral details—exactly the pattern we see in the Gospels. He notes that the relatively short time between Jesus’ ministry and Gospel composition (20-40 years) is insufficient for the kind of legendary development critics often assume. Most crucially, he demonstrates that eyewitnesses would have served as “quality control” for Gospel traditions during this period, correcting significant distortions.

DATING OF THE GOSPELS: OUR RELATED POSTS

Editor's Pick

The Throne-Room Vision: Who Did Isaiah See?

The scene is unforgettable: Isaiah stands in the temple, and suddenly the veil between heaven and earth tears open. He [...]

The Angel of the Lord: Can We Be Certain It Was Christ All Along?

Throughout the Old Testament, a mysterious figure appears: the Angel of the LORD. He speaks as God, bears God’s name, [...]

SUPPORT US:

Feel the Holy Spirit's gentle nudge to partner with us?

Donate Online:

Account Name: TRUTHS TO DIE FOR FOUNDATION

Account Number: 10243565459

Bank IFSC: IDFB0043391

Bank Name: IDFC FIRST BANK