400 Years of Silence: What Was God Doing Between the Testaments?

“If God was so active in the Old Testament—speaking through prophets, performing miracles, guiding His people—where was He for 400 years?”

It’s a question that troubles sceptics and believers alike. After Malachi’s final prophecy around 400 BC, the heavens seemingly went silent. No prophets. No miracles. No “Thus says the LORD.” Just centuries of waiting until a baby’s cry broke the stillness in Bethlehem.

But what if this silence wasn’t divine neglect? What if those 400 years reveal something profound about how God works—not just in ancient history, but in our own seasons of seeming silence?

WHEN THE WORD OF THE LORD WAS RARE

The Bible itself acknowledges seasons of prophetic silence. In 1 Samuel 3:1, we read “the word of the LORD was rare in those days; there was no frequent vision.” Yet God hadn’t abandoned Israel—He was preparing the stage for Samuel’s ministry and eventually King David’s line, through which the Messiah would come.

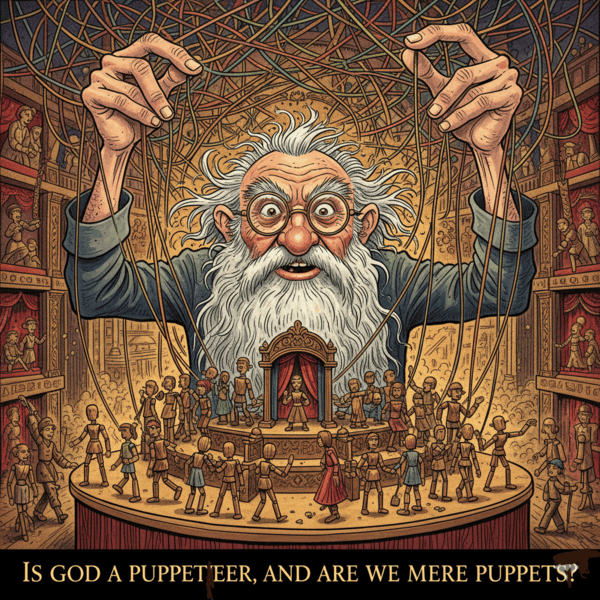

The Reformed tradition has understood God’s sovereignty extends over all of history, including the quiet seasons. The 400 years between Malachi and Matthew weren’t an unexplained gap in God’s plan. They were the fulfillment of prophecy itself—a divinely orchestrated intermission before the greatest divine intervention in human history.

THE SILENCE WAS PREDICTED

Here’s what many miss: Scripture itself prophesied the intertestamental period.

In Daniel 9:24-27, the prophet receives a stunning vision of “70 weeks” decreed for his people—a prophetic timeline pointing to the coming of “an anointed one, a prince.” Scholars have long recognised this as roughly 483 years from the decree to rebuild Jerusalem to the arrival of the Messiah. God was telling His people exactly when to expect their Deliverer.

The silence wasn’t mysterious—it was on the calendar.

Even Malachi’s final words point beyond the gap: “Behold, I will send you Elijah the prophet before the great and awesome day of the LORD comes” (Malachi 4:5). The last Old Testament prophet promised a future prophet, creating anticipation for what lay ahead. When John the Baptist arrived “in the spirit and power of Elijah” (Luke 1:17), he was the hinge between silence and the Word made flesh.

The intertestamental period wasn’t God going off-script. It was the script.

PROVIDENCE DISGUISED AS SILENCE

While no prophets spoke, God’s sovereign hand was anything but idle. He was orchestrating world history with surgical precision, preparing the perfect conditions for the gospel to explode across the globe.

Greek became the universal language. When Alexander the Great conquered the known world after 333 BC, he didn’t just establish an empire—he created a linguistic highway for the gospel. Koine Greek became the common tongue from Spain to India. This wasn’t accidental. God was preparing the vehicle for His written Word. The New Testament would be penned in Greek, making it immediately accessible across the Mediterranean world. The Septuagint—the Greek translation of Hebrew Scriptures completed around 250 BC—meant even diaspora Jews could read God’s promises in the world’s lingua franca.

Roman roads paved the way for gospel feet. By the time Jesus was born, Rome had constructed over 50,000 miles of stone-paved roads connecting the empire. The Pax Romana brought unprecedented travel safety. This infrastructure would prove essential for the apostles’ missionary journeys. Paul’s three missionary journeys, covering thousands of miles and dozens of cities (Acts 13-28), would have been impossible without Rome’s providential preparation.

Notice Paul’s own theology of timing: “When the fullness of time had come, God sent forth his Son” (Galatians 4:4). The “fullness of time” wasn’t arbitrary—it was the convergence of language, infrastructure, and political stability that God had been orchestrating for centuries.

The Jewish diaspora created gospel beachheads. God scattered His people throughout the known world, and wherever they went, they established synagogues. By the first century, Jewish communities existed in every major city. These became Paul’s strategic starting points in city after city: Salamis (Acts 13:5), Iconium (Acts 14:1), Thessalonica (Acts 17:1-2). God was planting seed-beds for gospel harvest decades before the seeds arrived.

Religious hunger intensified. The intertestamental period saw the development of Pharisees, Sadducees, scribes, and synagogue culture. While these groups would often oppose Jesus, their existence demonstrated a people hungry for God’s word, debating Scripture, and sharpening theological categories about resurrection, Messiah, and the age to come. Even their resistance to Christ revealed how deeply Israel longed for divine intervention.

MORE THAN COVENANT CURSES

Some suggest the silence resulted from Deuteronomy 28’s covenant curses—that God withdrew because of Israel’s persistent disobedience. There’s partial truth here: Israel’s exile certainly fulfilled prophetic warnings (2 Kings 17:13-14). But this explanation falls short.

- First, it doesn’t account for the precision of the Messiah’s arrival. Punishment is reactive; what we see in the 400 years is proactive preparation.

- Second, remember God’s unconditional covenant with Abraham—”in you all the families of the earth shall be blessed” (Genesis 12:3)—couldn’t be nullified by Israel’s failures. Paul insists “the gifts and the calling of God are irrevocable” (Romans 11:29).

The silence wasn’t punitive abandonment. It was purposeful staging. God wasn’t punishing the world; He was preparing it for the universal blessing He’d promised Abraham two millennia earlier.

THE GOD WHO WORKS IN SILENCE

The 400 silent years reveal something essential about divine providence: God doesn’t need to speak audibly to accomplish His purposes. He controls nations (Proverbs 21:1), raises and deposes kings (Daniel 4:35), and works all things according to His will (Ephesians 1:11)—whether we hear His voice or not.

For believers today facing seasons of divine silence—when prayers seem unanswered, when guidance feels absent, when God seems distant—the intertestamental period offers profound comfort. God’s apparent quiet doesn’t mean absence. His silence doesn’t signal neglect.

As Habakkuk learned in his own time of waiting: “For still the vision awaits its appointed time; it hastens to the end—it will not lie. If it seems slow, wait for it; it will surely come” (Habakkuk 2:3).

The Word may have been rare between the testaments. But the Word was coming. And He did.

RELATED FAQs

Why don’t Reformed Christians include the Apocryphal books in the Bible if they were written during this period? The Apocrypha (books like 1-2 Maccabees, Tobit, Judith, and others) were written during the intertestamental period, but the Reformed tradition doesn’t recognise them as Scripture for several key reasons. First, these books were never part of the Hebrew canon that Jesus and the apostles used—Jesus referenced the Hebrew Scriptures from “Abel to Zechariah” (Luke 11:51), the exact boundaries of the Jewish canon. Second, the Apocryphal books themselves never claim divine inspiration and contain historical errors and theological teachings contrary to the rest of Scripture (like praying for the dead in 2 Maccabees 12:45-46). While these books have historical value for understanding the intertestamental period, they lack the prophetic authority and divine inspiration that mark true Scripture.

- Did any genuine miracles or supernatural events occur during the 400 silent years? According to Josephus and Jewish tradition, the intertestamental period saw no prophetic miracles like those in the Old Testament, and this was understood as a mark of prophetic absence. The rabbis taught that after Haggai, Zechariah, and Malachi died, “the Holy Spirit departed from Israel”—meaning the prophetic gift ceased. The book of 1 Maccabees itself acknowledges this, stating there was “great distress in Israel, such as had not been since the time that prophets ceased to appear” (1 Maccabees 9:27). This absence of miracles actually makes the explosive return of supernatural power in Jesus’ ministry more significant—when God broke the silence, He did so with undeniable divine authority that echoed the exodus itself.

- How do modern Reformed scholars view the 400 silent years? Contemporary theologians emphasise the intertestamental period as a demonstration of God’s covenantal faithfulness and meticulous providence. Michael Horton argues the silence highlights God’s promise-keeping character: He told His people through the prophets when the Messiah would come, then kept that appointment with history. Sinclair Ferguson notes the period reveals how God works through “ordinary” historical processes—empires, languages, migrations—to accomplish extraordinary redemptive purposes. DA Carson points out the silence created an “eschatological urgency” in first-century Judaism, with various groups (Pharisees, Essenes, Zealots) offering competing visions of how God would break in again, making Jesus’ arrival explosively controversial and impossible to ignore.

What major Old Testament prophecies were being fulfilled during the silent years that people might not realise? Several crucial prophecies found fulfillment during this period without anyone recognising it at the time. Daniel’s prophecy of four kingdoms (Daniel 2 and 7)—Babylon, Medo-Persia, Greece, and Rome—was unfolding exactly as predicted, with Greek and then Roman rule establishing themselves during these centuries. The scattering of Jews “among all peoples, from one end of the earth to the other” (Deuteronomy 28:64) reached its fullest extent during this diaspora, providentially positioning witnesses in every nation for the gospel. Even seemingly small details like Zechariah’s prophecy that the Messiah would enter Jerusalem on a donkey (Zechariah 9:9) required the political conditions where Jerusalem was intact but under foreign rule—precisely what Roman occupation provided.

- How did Jewish worship and theology develop during this period, and why does that matter for understanding the New Testament? The intertestamental period saw massive developments in Jewish religious life that directly shaped the world Jesus entered. The synagogue system emerged during the Babylonian exile and flourished during these centuries, creating local centres for Scripture reading and teaching that became the template for early Christian gatherings. The party divisions—Pharisees (emphasizing oral law and resurrection), Sadducees (Temple-focused, denying resurrection), and Essenes (separatist purists)—crystallised theological debates Jesus would directly engage. Messianic expectations intensified with diverse views ranging from military liberators to priestly figures to heavenly judges, making Jesus’ teaching about the kingdom deliberately surprising.

- What was happening in Jewish apocalyptic literature during this time, and how did it prepare for Jesus? The intertestamental period produced extensive apocalyptic literature (books like 1 Enoch, 4 Ezra, 2 Baruch) that wrestled with why God’s people still suffered under foreign oppression despite returning from exile. These writings developed elaborate visions of heaven, demons, angels, resurrection, and final judgement—themes that appear throughout the New Testament. While these books aren’t inspired Scripture, they show the theological questions consuming first-century Jews: When would God’s kingdom come? How would God judge the nations? What about righteous people who died before deliverance? Jesus’ teaching about the Son of Man, the resurrection, and the coming kingdom resonated precisely because centuries of apocalyptic expectation had prepared Jewish minds for these categories. The 400 years weren’t just political preparation—they were theological preparation for understanding the Messiah when He arrived.

Are there any recorded Jewish traditions or prayers from this period that acknowledged the prophetic silence? Yes, and they’re deeply poignant. Jewish tradition preserved in the Talmud speaks of an inferior form of divine communication that replaced direct prophecy after Malachi. This was seen as God’s distant echo rather than His direct speech, showing they knew something had changed. The prayer literature from this period, including Psalms of Solomon (first century BC) and prayers preserved at Qumran, repeatedly plead for God to “remember” His covenant and “not delay” His salvation. There’s a palpable sense of longing and confusion—why had God withdrawn His presence? One Qumran text speaks of waiting “until the coming of the Prophet and the Messiahs of Aaron and Israel,” showing they knew prophetic silence would end with the Anointed One. This makes John the Baptist’s emergence after 400 years of silence all the more electrifying—the heavens were finally speaking again.

OUR RELATED POSTS

Editor's Pick

Why Do People Hate the Doctrine of Election?

…WHEN THEY REALLY SHOULDN’T Few Bible doctrines provoke stronger reactions than election. The idea that God chose some for salvation [...]

The Doctrine of Providence: Does God Really Govern All Things?

You’re sitting in the doctor’s office when the diagnosis lands like a thunderclap. Your mind races: Why this? Why now? [...]

No Decay, No Defeat: What It Means That Christ’s Body Saw No Corruption

On the Day of Pentecost, Peter stood before thousands and made a startling claim: David's body decayed in the tomb, [...]

SUPPORT US:

Feel the Holy Spirit's gentle nudge to partner with us?

Donate Online:

Account Name: TRUTHS TO DIE FOR FOUNDATION

Account Number: 10243565459

Bank IFSC: IDFB0043391

Bank Name: IDFC FIRST BANK