The Valley of Dry Bones: What Does Ezekiel’s Vision Mean?

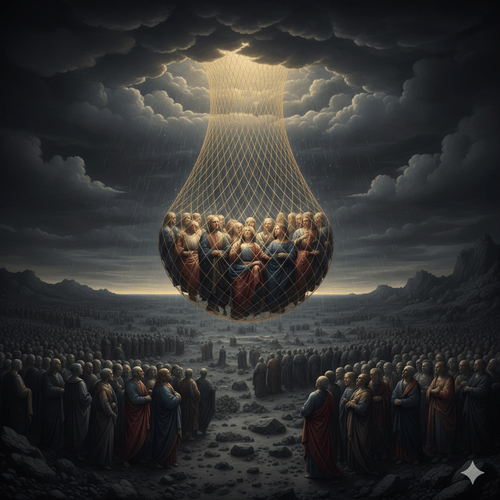

The hand of the LORD set the prophet Ezekiel down in a valley. What he saw there would have stolen his breath: bones scattered across the ground as far as the eye could see—sun-bleached, disconnected, utterly lifeless. “Very dry,” Scripture says, emphasising their hopeless state. Then God asked a question that still echoes through the centuries: “Son of man, can these bones live?”

This haunting vision raises profound questions. Is Ezekiel 37 describing a literal resurrection? A metaphor for national revival? Or something deeper still? The Reformed tradition recognises layered meanings in this passage—primarily national restoration, typologically revealing sovereign grace in salvation, and ultimately pointing toward bodily resurrection. But we need not speculate, for God Himself interprets the text for us.

THE CONTEXT OF DESPAIR

Ezekiel prophesied between 593-571 BC to Jewish exiles in Babylon. Jerusalem lay in ruins, the temple destroyed, God’s people scattered among the nations. Their anguished cry appears in verse 11: “Our bones are dried up, our hope is lost; we are cut off completely.” They felt dead as a nation, cut off from God’s promises.

Yet this vision follows immediately after God’s promise in Ezekiel 36:22-32 to give His people a new heart and a new spirit. The context is covenant faithfulness: God will act, not because Israel deserves it, but “for my holy name’s sake.” The literary structure matters—first Ezekiel narrates the vision (verses 1-10), then provides the divine interpretation (verses 11-14). God Himself tells us what it means.

THE VISION UNFOLDS

The scene is overwhelming death. Bones lie scattered. They’re “very dry”—they’ve been dead a long time. Humanly speaking, restoration is impossible. When God asks, “Can these bones live?” Ezekiel’s answer is telling: “O Lord GOD, you know.” Only divine power could accomplish such a thing.

Then comes the extraordinary command: “Prophesy to these bones.” As Ezekiel speaks God’s word, the bones begin to rattle and come together. Sinews appear, then flesh, then skin—yet “there was no breath in them.” The external form is there, but life is absent. God commands again: “Prophesy to the breath.” The Hebrew word ruach means breath, wind, and Spirit—and here all three converge. Breath from the four winds enters the bodies, and they stand, “an exceedingly great army.”

FIRST: THE NATIONAL RESTORATION

We need not guess at the vision’s meaning. God declares: “These bones are the whole house of Israel.” This is about national restoration from exile. God promises to open their graves, bring them back to the land of Israel, and put His Spirit within them. They will live again as a people.

The historical fulfillment came partially in the Jews’ return from Babylon under Ezra and Nehemiah. Yet it remained incomplete, pointing forward to something greater. Supporting texts highlight this: Ezekiel 36:24-28 promises both physical return and spiritual renewal; Jeremiah 31:31-34 speaks of the new covenant; Isaiah 40:1-2 proclaims comfort to exiled Jerusalem.

The Westminster Confession (8.6) reminds us Christ’s work includes “gathering and defending” His people. God’s sovereign initiative redeems a corporate people—not isolated individuals alone, but a covenant community restored by grace.

NEXT: A PERFECT PICTURE OF SALVATION

For Reformed theology, Ezekiel’s vision becomes a perfect illustration of spiritual regeneration—from death to life by sovereign grace alone.

Total depravity appears vividly here. These bones aren’t sick or sleeping—they’re dead. “Very dry” emphasises complete inability, no latent life remaining. As Paul writes, we were “dead in trespasses and sins” (Ephesians 2:1). The Canons of Dort (I.1,3) affirm fallen humanity cannot respond to God apart from His regenerating work.

Irresistible grace unfolds before our eyes. God sends human agents to prophesy to dead bones—His word creates what it commands. The breath comes from outside; the bones contribute nothing. This is monergistic regeneration: God’s Spirit sovereignly gives life. As Jesus said, “The dead will hear the voice of the Son of God, and those who hear will live” (John 5:25). The Westminster Shorter Catechism (Q.31) defines effectual calling as “the work of God’s Spirit, whereby…He doth persuade and enable us to embrace Jesus Christ.”

This is every believer’s story. The bones don’t cooperate—they can’t. Neither do we in our salvation. Life comes entirely from God’s initiative. Repeatedly the text declares, “You shall know that I am the LORD”—salvation is for God’s glory.

FINALLY: LOOKING FORWARD TO THE FINAL RESURRECTION

While not the primary meaning, this vision anticipates bodily resurrection too. It echoes passages such as Daniel 12:2, Romans 8:11 and 1 Corinthians 15:42-49, where the same Spirit who raised Christ will raise the dead at His return. Jesus Himself connected spiritual awakening (John 5:25) with the final resurrection (John 5:28-29). Ezekiel 37 thus demonstrates God’s absolute power over death itself.

The Westminster Confession (32.2-3) grounds bodily resurrection in Christ’s power—the same power that speaks to dry bones and raises the dead.

FROM DEATH TO LIFE

Ezekiel’s vision reveals God’s character: He is faithful to His promises and sovereign over death itself. National restoration, spiritual regeneration, bodily resurrection—all flow from the same divine power. Our salvation mirrors Israel’s: God speaking life into death, breath into lifeless bones.

The vision ends with God’s unshakable promise: “I, the LORD, have spoken, and I will do it.” In that declaration rests our hope—not in our ability to respond, but in His power to give life. Can these bones live? Yes—because God commands it, and His Spirit makes it so.

EZEKIEL 37: THE VALLEY OF DRY BONES—RELATED FAQ

What did the Reformers say about Ezekiel 37? John Calvin emphasised this vision demonstrates God’s omnipotence in restoring His people when all human hope is exhausted. He interpreted the passage primarily as national restoration but saw it as teaching God’s word is “efficacious”—it accomplishes what it declares, whether in national revival or individual conversion. Calvin stressed that just as the bones had no power to reassemble themselves, sinners have no ability to regenerate themselves apart from God’s sovereign Spirit.

- How did Matthew Henry interpret the vision of dry bones? Matthew Henry saw threefold instruction: comfort to Israel in captivity, encouragement to ministers preaching to spiritually dead congregations, and evidence of God’s power to raise the dead at the last day. He noted ministers must prophesy to dry bones even when success seems impossible, trusting God’s Spirit to give life. Henry beautifully wrote “the Spirit of life from God” must accompany the word, or it remains merely “a dead letter to dead souls.”

- Why does God ask “Can these bones live?” if He already knows the answer? This rhetorical question serves to highlight to us human impossibility and divine possibility. God engages Ezekiel in the prophetic moment, teaching him restoration depends entirely on God’s power, not human assessment. Ezekiel’s wise response—“O Lord GOD, you know”—acknowledges only God can determine and accomplish what seems humanly impossible.

What’s the significance of the two-stage process (bones forming, then breath entering)? The two stages distinguish between outward reformation and inward regeneration. The bones can be fully assembled with flesh and skin yet remain lifeless without God’s Spirit—a warning against mere external religion or cultural Christianity. Reformed theology sees this as illustrating that intellectual assent, moral improvement, or religious ritual cannot produce spiritual life; only the Spirit’s regenerating work brings true life.

- Why does Ezekiel prophesy to the “four winds”? The four winds represent universality—God’s Spirit comes from every direction, symbolising His omnipresence and unlimited power. Some Reformed commentators see prophetic hints here of the Spirit’s work beyond Israel to all nations. The phrase also emphasizes that life comes entirely from outside the bones themselves; they cannot generate their own breath, just as sinners cannot produce their own regeneration.

- Does this vision support a future mass conversion of ethnic Israel? Reformed interpreters differ on this question. Some see Ezekiel 37 as supporting Romans 11:25-26’s promise that “all Israel will be saved,” expecting a future large-scale Jewish conversion. Others interpret both passages as referring to the fullness of God’s elect people (Jew and Gentile together in Christ) rather than a separate ethnic restoration. All agree that any such conversion would be by sovereign grace, not human merit.

What does the phrase “open your graves” (v. 12) mean if they’re in Babylonian exile, not literally buried? “Graves” is metaphorical language depicting exile as a kind of national death and burial. Israel felt entombed in Babylon, cut off from their land and God’s presence. The promise to “open your graves and bring you up” uses resurrection imagery to describe returning from exile—they’d be “raised” from the death of captivity to new life in their homeland, a restoration as dramatic as resurrection itself.

EZEKIEL 37: THE VALLEY OF DRY BONES—OUR RELATED POSTS

Editor's Pick

Why Do People Hate the Doctrine of Election?

…WHEN THEY REALLY SHOULDN’T Few Bible doctrines provoke stronger reactions than election. The idea that God chose some for salvation [...]

The Doctrine of Providence: Does God Really Govern All Things?

You’re sitting in the doctor’s office when the diagnosis lands like a thunderclap. Your mind races: Why this? Why now? [...]

No Decay, No Defeat: What It Means That Christ’s Body Saw No Corruption

On the Day of Pentecost, Peter stood before thousands and made a startling claim: David's body decayed in the tomb, [...]

SUPPORT US:

Feel the Holy Spirit's gentle nudge to partner with us?

Donate Online:

Account Name: TRUTHS TO DIE FOR FOUNDATION

Account Number: 10243565459

Bank IFSC: IDFB0043391

Bank Name: IDFC FIRST BANK