Elisha’s Curse on 42 Youth: Divine Justice or Overreaction?

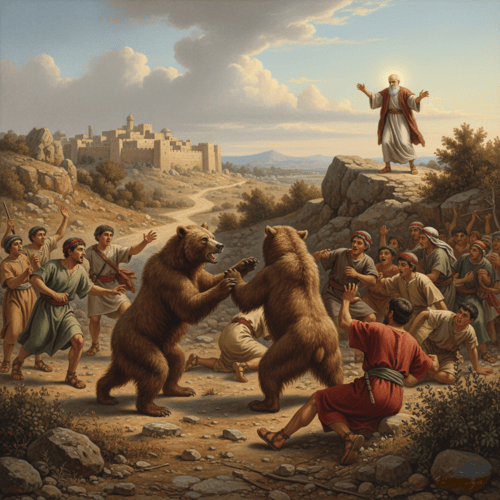

The story stops us cold. The prophet Elisha, walking toward Bethel, encounters a group of young men who mock him: “Go up, you baldhead!” Elisha curses them in the name of the Lord, and immediately two bears emerge from the woods and maul 42 of them (2 Kings 2:23-25).

For modern sensibilities, this seems like a troubling overreaction. Killed by bears for calling someone bald? Where’s the proportionality? Where’s the mercy? And why did God act so swiftly here when He seems to ignore our prayers for justice today?

The Reformed tradition, drawing on careful exegesis and theological reflection, offers compelling answers that vindicate both Elisha’s action and God’s character.

CONTEXT CHANGES EVERYTHING

First, we must resist reading our modern assumptions into an ancient text. The Hebrew word na’arim doesn’t mean “little children”—it refers to young men, likely of military age. John Calvin observed these were “idle and dissolute young men,” not toddlers. The same term describes Isaac when he’s old enough to carry wood up a mountain (Genesis 22:5) and Joseph at 17 (Genesis 37:2).

Second, this was organised, aggressive mockery, not innocent teasing. The sheer number—42 mauled from what was likely a larger mob—indicates this was intimidation, possibly even a threat to the prophet’s safety.

But the deepest context is covenantal and geographical. Bethel wasn’t just any town—it was ground zero for Israel’s apostasy. King Jeroboam had established golden calf worship there (1 Kings 12:28-29), creating a rival religious centre to Jerusalem. For generations, Bethel had been the epicentre of covenant rebellion, training Israelites to violate the first and second commandments.

This was spiritual warfare at a critical moment in Israel’s history. These young men weren’t simply making fun of a bald man. Their taunt—”Go up, you baldhead!”—was a deliberate rejection of Elijah’s recent ascension to heaven and a mockery of prophetic succession itself. As Francis Turretin argued in his Institutes, attacks on God’s appointed prophets were attacks on the divine Word they represented. The Westminster Larger Catechism (Q. 113) classifies contempt for God’s ordinances as a violation of the third commandment—taking the Lord’s name in vain.

DIVINE JUSTICE, NOT HUMAN VENGEANCE

Notice carefully: Elisha didn’t summon the bears. He pronounced a curse “in the name of the LORD,” and God sovereignly chose whether and how to act. Calvin emphasises this distinction: “God would not have executed such severe vengeance had not the wickedness of those scoffers been desperate and past cure.”

The judgement wasn’t Elisha’s personal revenge—it was divine validation of prophetic authority at a moment when Israel teetered on the edge of complete apostasy.

But wasn’t it still disproportionate? Not within the covenant framework Israel had chosen. The Mosaic covenant came with explicit blessings for obedience and curses for rebellion (Deuteronomy 28). Israel had just endured the wicked reigns of Ahab and Jezebel, marked by Baal worship, prophetic persecution, and covenant infidelity. God’s patience had been extended for decades.

As Iain Duguid notes in the ESV Expository Commentary, this dramatic act established Elisha’s credentials at Israel’s spiritual crisis point. Without respect for prophetic authority, Israel had no access to God’s Word—and without God’s Word, the nation would perish. The bears protected the prophetic office essential for Israel’s survival.

Philip Ryken observes immediate judgements like this mark pivotal redemptive-historical moments. Compare Nadab and Abihu’s unauthorised fire (Leviticus 10), Korah’s rebellion against Moses (Numbers 16), or Uzzah touching the Ark (2 Samuel 6). At critical junctures, God demonstrates His holiness isn’t negotiable.

The pedagogical purpose was clear: mock God’s Word, and you mock God Himself. John Owen wrote that when God’s patience reaches its limit, judgement serves to warn others and vindicate divine authority (Works, Vol. 10). This single event likely prevented countless other acts of contempt against prophets throughout Israel.

WHY HERE AND NOT ELSEWHERE?

This raises our final question: If God acted so swiftly here, why doesn’t He always respond immediately to prophetic words or our prayers?

The Westminster Confession (5.3) distinguishes between God’s “ordinary” and “extraordinary” providence. Not every prophetic pronouncement produces visible judgement, and most prayers aren’t answered with immediate miraculous intervention. God’s timing serves His larger redemptive purposes.

Special moments in salvation history—the establishment of the prophetic office, the founding of the early church (remember Ananias and Sapphira in Acts 5)—sometimes require dramatic divine validation. These aren’t the norm; they’re calibrated interventions at critical transition points.

But here’s the deeper mercy: most sin doesn’t bring immediate judgement. This demonstrates God’s patience, not His indifference. As 2 Peter 3:9 reminds us, “The Lord is not slow to fulfil his promise as some count slowness, but is patient toward you, not wishing that any should perish, but that all should reach repentance.”

Calvin wrote: “God sometimes displays examples of His vengeance that others might be led to repentance.” Selective judgements serve as warnings to spare many others. Every act of rebellion deserves immediate judgement; that most judgement is mercifully delayed reveals God’s grace, not injustice.

THE GOSPEL IN THE STORY

For Christians, this troubling story ultimately magnifies the gospel. Those bears represent what all covenant-breakers—including us—actually deserve for treating God’s Word with contempt. Every casual dismissal of Scripture, every eye-roll at biblical authority, every moment we’ve mocked what God takes seriously merits judgement.

But Jesus bore the curse we deserve (Galatians 3:13). The wrath that should have torn us apart was absorbed by Christ on the cross. The gospel transforms mockers into worshipers, rebels into sons and daughters.

RELATED FAQs

Were these really young children or grown men? The Hebrew ne’arim qetannim (literally “small young men”) has caused confusion, but context clarifies. Matthew Henry notes these were youths old enough to know better—likely teenagers to young adults who’d been raised under apostate teaching in Bethel. Derek Kidner observes the term can describe anyone from adolescence to early adulthood, and the organised nature of their mockery suggests deliberate malice rather than childish ignorance. RC Sproul emphasises their accountability before God wasn’t based solely on age but on their willful rejection of divine authority in a covenant community.

- Why were there exactly 42 mauled? Does the number hold any significance? The precise number 42 appears several times in Scripture with varying significance, though Reformed commentators generally avoid over-allegorizing. Dale Ralph Davis suggests the number emphasises the magnitude of the judgement—this wasn’t one or two casualties but a devastating event that would reverberate throughout the region. The specificity also serves as a historical marker, demonstrating this was a real event with real consequences, not a parable or legend. Some note 42 months represent a period of judgement in Revelation, though most Reformed scholars see this as historical record rather than symbolic numerology.

- What happened to the bears afterward? Did they continue attacking people? Scripture is silent on this, which itself is instructive. Sinclair Ferguson notes the bears’ appearance and disappearance serve God’s specific purpose—they weren’t rogue animals but instruments of divine judgement. Matthew Poole’s commentary suggests the bears returned to the wilderness after accomplishing God’s intent, similar to how the lions that killed the disobedient prophet (1 Kings 13:24) didn’t devour him but stood guard. The miraculous element isn’t just that bears appeared, but that they acted with precise purpose and restraint, mauling exactly what God intended before departing.

Did Elisha feel remorse after this incident? Should he have? The text records no regret from Elisha, and Reformed commentators affirm he acted rightly. JC Ryle observes that true prophets didn’t speak from personal emotion but divine commission—Elisha’s curse wasn’t a heated outburst but a measured prophetic pronouncement. John Gill argues any remorse would have implied God acted wrongly in vindicating His prophet, which would itself be impious. Charles Spurgeon noted faithful ministers must sometimes pronounce God’s judgement without sentimentality, trusting divine wisdom over human feelings. The prophet’s role was to be God’s mouthpiece, not to second-guess divine justice.

- How does this compare to Jesus saying “Let the little children come to me”? This question reveals a common misreading—these weren’t little children, and the contrast isn’t as stark as assumed. Michael Horton notes both Elisha and Jesus upheld divine holiness while showing mercy appropriate to their distinct redemptive roles. Old Testament judgements often foreshadowed the greater judgement Christ would bear on the cross. Kevin DeYoung observes that Jesus came to absorb God’s wrath, but He also spoke of millstones for those who harm little ones and pronounced woes on unrepentant cities (Matthew 11:20-24). Both prophets declared God’s character; the difference lies in redemptive timing, not divine temperament.

- Are there other examples of immediate divine judgement in Scripture that help us understand this? Yes, and they follow a pattern. James Montgomery Boice pointed to Uzzah’s death for touching the Ark (2 Samuel 6:6-7), Ananias and Sapphira struck down for lying (Acts 5:1-11), and Herod eaten by worms for accepting worship (Acts 12:21-23). Each occurred at critical moments requiring clear demonstration of God’s holiness. TM Moore notes these aren’t arbitrary but serve as “judicial signposts” at covenant transitions or when God’s nature is particularly at stake. The principle remains consistent: extraordinary circumstances sometimes demand immediate, visible judgment to instruct God’s people.

If this story is acceptable, does it justify modern religious leaders pronouncing curses? Absolutely not, and Reformed theology is clear on this distinction. Carl Trueman emphasises that Elisha operated under direct prophetic anointing with confirmed miraculous authority—modern pastors have no such warrant. The cessation of apostolic sign-gifts means we cannot expect immediate miraculous vindication of our pronouncements. Richard Phillips notes Christian ministers today proclaim God’s Word faithfully but leave judgement entirely to God without expecting bears to appear. Our calling is to preach, pray, and trust God’s timing—not to invoke curses expecting immediate supernatural enforcement. This was a unique redemptive-historical moment, not a template for church discipline.

OUR RELATED POSTS

- Why Was Touching the Ark of God a Fatal Mistake?

- Death Penalty For Blasphemy: Was God Too Harsh?

- Why Did God Punish Lot’s Wife? What Was Her Sin

- Acts 5: Was God Too Harsh With Ananias and Sapphira?

- Why Did God Destroy Sodom and Gomorrah? The Full Story

- Slaughter of the Canaanites: Would a Loving God Command It?

Editor's Pick

Why Do People Hate the Doctrine of Election?

…WHEN THEY REALLY SHOULDN’T Few Bible doctrines provoke stronger reactions than election. The idea that God chose some for salvation [...]

The Doctrine of Providence: Does God Really Govern All Things?

You’re sitting in the doctor’s office when the diagnosis lands like a thunderclap. Your mind races: Why this? Why now? [...]

No Decay, No Defeat: What It Means That Christ’s Body Saw No Corruption

On the Day of Pentecost, Peter stood before thousands and made a startling claim: David's body decayed in the tomb, [...]

SUPPORT US:

Feel the Holy Spirit's gentle nudge to partner with us?

Donate Online:

Account Name: TRUTHS TO DIE FOR FOUNDATION

Account Number: 10243565459

Bank IFSC: IDFB0043391

Bank Name: IDFC FIRST BANK