First Church Fathers: Early Support for Jesus’ Historicity

In the quest to understand the historical Jesus, we often turn to the Gospels and other New Testament writings. However, another rich source of information lies in the works of the early church fathers—Christian leaders and theologians who lived in the centuries immediately following Jesus’ life. These writers, some of whom claim connections to the apostles themselves, provide a crucial link between the time of Jesus and the establishment of Christianity as a major world religion. Their testimonies not only corroborate the New Testament accounts but also offer additional insights into how early Christians understood and defended their faith in Jesus as a real, historical figure. This post explores what these influential early church fathers had to say about Jesus, building a compelling case for His historicity.

Clement of Rome (c. 35-99 CE) Clement of Rome, one of the earliest and most significant church fathers, served as the bishop of Rome. His letter known as “1 Clement,” written around 96 CE, addresses the church in Corinth. In this letter, Clement refers to Jesus Christ as the Son of God, emphasizing His sacrificial death and resurrection. Clement writes, “Let us look steadfastly to the blood of Christ and see how precious that blood is to God, which, having been shed for our salvation, has set the grace of repentance before the whole world” (1 Clement 7:4). This early reference highlights the foundational Christian belief in Jesus’ redemptive death.

Ignatius of Antioch (c. 35-108 CE) Ignatius of Antioch, a bishop and martyr, wrote a series of letters to various churches while on his way to Rome for execution. These letters, dating from around 110 CE, provide crucial insights into early Christian theology. Ignatius emphasizes the reality of Jesus’ incarnation, crucifixion, and resurrection. In his letter to the Smyrnaeans, he asserts, “He was truly born, truly persecuted under Pontius Pilate, truly crucified and died, in the sight of beings in heaven and on earth and under the earth” (Smyrnaeans 2:1). Ignatius’ insistence on the historical facts of Jesus’ life counters early heretical claims that denied Jesus’ humanity.

Papias of Hierapolis (c. 60-130 CE) Papias, the Bishop of Hierapolis, wrote the “Exposition of the Sayings of the Lord” around 120-130 CE. Although his work survives only in fragments quoted by later authors, particularly Eusebius, it provides valuable insights into the origins of the Gospels. Papias claimed to have gathered information from those who knew the apostles directly, writing, “If, then, any one who had attended on the elders came, I asked minutely after their sayings, – what Andrew or Peter said, or what was said by Philip, or by Thomas, or by James, or by John, or by Matthew, or by any other of the Lord’s disciples” (quoted in Eusebius, Church History, 3.39.4). His testimony is particularly important for asserting that Mark’s Gospel was based on Peter’s preaching and that Matthew originally wrote in Hebrew, providing early evidence for the apostolic origins of these Gospels.

Quadratus of Athens (c. 125 CE) Quadratus was one of the earliest Christian apologists, addressing his defence of Christianity to Emperor Hadrian around 124-125 CE. While most of his work is lost, a significant fragment is preserved by Eusebius. In this fragment, Quadratus provides a striking claim about the longevity of Jesus’ miracles: “But the works of our Saviour were always present, for they were genuine: those that were healed, and those that were raised from the dead, who were seen not only when they were healed and when they were raised, but were also always present; and not merely while the Saviour was on earth, but also after his death, they were alive for quite a while, so that some of them lived even to our day” (quoted in Eusebius, Church History, 4.3.2). This statement is notable for suggesting that recipients of Jesus’ miracles were still alive in Quadratus’ time, providing a potential bridge between Jesus’ ministry and the early 2nd century.

Polycarp of Smyrna (c. 69-155 CE) Polycarp, a disciple of the apostle John and bishop of Smyrna, played a pivotal role in preserving apostolic teachings. His letter to the Philippians, written around 110-140 CE, contains numerous references to Jesus Christ. Polycarp speaks of Jesus’ sinless life, His teachings, and His resurrection. He writes, “But He who raised Him up from the dead will raise up us also, if we do His will and walk in His commandments and love what He loved” (Philippians 2:2). Polycarp’s direct connection to the apostolic tradition underscores the continuity of belief in the historical Jesus.

Justin Martyr (c. 100-165 CE) Justin Martyr, an early Christian apologist, wrote extensively to defend Christianity against pagan criticisms. His “First Apology,” written around 155 CE, offers a detailed account of Jesus’ life and teachings, emphasizing their fulfillment of Old Testament prophecies. Justin describes Jesus as the incarnate Word of God who performed miracles, was crucified under Pontius Pilate, and rose from the dead. He writes, “He was born of a virgin, as both Isaiah and the other prophets predicted. He grew up as a man and showed Himself as the Son of God by the miracles He performed” (First Apology 33). Justin’s apologetic works provide a robust historical framework for understanding Jesus.

Irenaeus of Lyons (c. 130-202 CE) Irenaeus, bishop of Lyons, is best known for his work “Against Heresies,” written around 180 CE. This comprehensive treatise refutes various heresies and affirms the orthodox Christian faith. Irenaeus provides detailed accounts of Jesus’ life, emphasizing His incarnation, death, and resurrection. He writes, “He took up humanity into Himself, He offered Himself to the Father on behalf of all men, thus fulfilling the will of the Father in all things” (Against Heresies 5:1:1). Irenaeus’ insistence on the historical reality of Jesus’ life and work serves as a critical defence against early Gnostic beliefs.

Tertullian (c. 160-225 CE) Tertullian, an early Christian apologist from Carthage, wrote extensively on theology and apologetics. In his work “Apology,” written around 197 CE, Tertullian defends the historicity of Jesus and the credibility of the Christian faith. He argues for the factual basis of Jesus’ crucifixion and resurrection, stating, “The fame of Jesus had spread abroad; they were not ignorant that He was the Christ, who was expected, who was crucified, who died, who rose again” (Apology 21). Tertullian’s writings underscore the widespread acceptance of Jesus’ historical existence within the early Christian community.

Origen of Alexandria (c. 185-254 CE) Origen, a prolific theologian and scholar, made significant contributions to early Christian thought. In his work “Against Celsus,” written around 248 CE, Origen responds to the critiques of the pagan philosopher Celsus. Origen defends the historical reality of Jesus, asserting the authenticity of the Gospel accounts. He writes, “Jesus, who has both taught and done the greatest things, was truly born, and His life and actions were recorded by His disciples” (Against Celsus 2:13). Origen’s detailed defence of Jesus’ life and ministry highlights the historical grounding of Christian beliefs.

Conclusion

The writings of the early church fathers present a consistent and detailed portrait of Jesus Christ as a historical figure. From Clement of Rome in the late 1st century to Origen in the mid-3rd century, these influential Christian leaders affirmed the core elements of Jesus’ life, death, and resurrection. Their works not only preserve and interpret the teachings of Jesus but also defend the historical reality of His existence against both pagan critics and heretical movements within early Christianity. The breadth, depth, and early date of their testimonies provide strong supporting evidence for the historicity of Jesus. As we piece together the historical puzzle of Jesus’ life, the early church fathers offer invaluable pieces that help complete the picture, reinforcing the foundation upon which Christian faith has been built for two millennia.

Related Reads:

- Exploring the Historicity of Jesus: Facts and Evidence

- Historicity Compared: Jesus and Ancient Leaders

- Ancient Non-Christian Writings on Jesus: Validating the Gospels

Editor's Pick

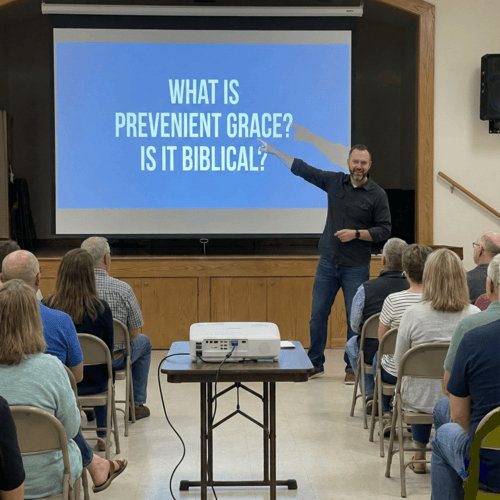

Prevenient Grace: 5 Reasons the Doctrine Fails

Can a spiritually dead person choose God? It’s one of the oldest questions in Christian theology. And how we answer [...]

Why Do People Hate the Doctrine of Election?

…WHEN THEY REALLY SHOULDN’T Few Bible doctrines provoke stronger reactions than election. The idea that God chose some for salvation [...]

The Doctrine of Providence: Does God Really Govern All Things?

You’re sitting in the doctor’s office when the diagnosis lands like a thunderclap. Your mind races: Why this? Why now? [...]

SUPPORT US:

Feel the Holy Spirit's gentle nudge to partner with us?

Donate Online:

Account Name: TRUTHS TO DIE FOR FOUNDATION

Account Number: 10243565459

Bank IFSC: IDFB0043391

Bank Name: IDFC FIRST BANK