In the World But Not Of It: What John 17:14-16 Really Means

Scrolling through social media, we’re bombarded by voices shouting for our allegiance—politics, trends, ideologies. As Christians, we feel the tension: how do we live faithfully in a world that often opposes God? Jesus’ words in John 17:14-16 offer the answer: “They are not of the world, just as I am not of the world… I do not ask that you take them out of the world, but that you keep them from the evil one.”

In the Reformed tradition, this means believers are transformed by God’s grace (John 3:3). We’re set apart from the world’s sinful ways, yet called to shine as salt and light (Matthew 5:13-16). Far from retreating, we’re to engage culture boldly, trusting God’s sovereign care. This post unpacks the biblical meaning and practical ways to live “in but not of” the world, glorifying Christ in every sphere. How do we as sanctified ambassadors transform culture without being transformed by it.

THE BIBLICAL FOUNDATION

When Jesus says his followers are “not of the world,” he’s not talking about geography. The Greek word kosmos here refers to the world-system in rebellion against God—its values, appetites, and ultimate loyalties. Christians live in creation but reject the spiritual orientation of fallen humanity.

This distinction echoes throughout Scripture. Paul commands us, “Do not be conformed to this world, but be transformed by the renewal of your mind” (Romans 12:2). John warns, “Do not love the world or the things in the world” (1 John 2:15). Paul declares, “Our citizenship is in heaven” (Philippians 3:20).

Scripture emphasises this dual citizenship. We inhabit earthly cities while belonging to a heavenly kingdom. Like Christ Himself, we’re physically present but spiritually distinct—a reality requiring constant discernment and grace.

WHAT “NOT OF THE WORLD” ACTUALLY MEANS

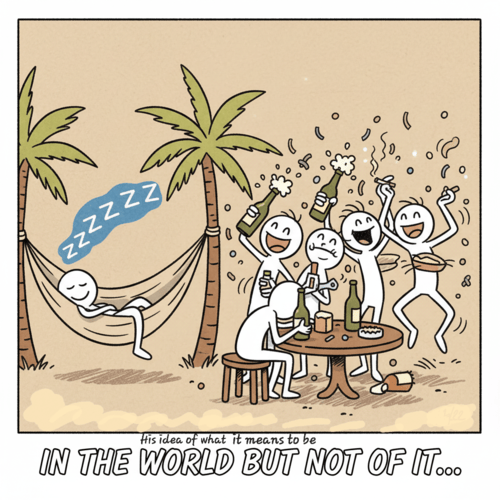

Spiritual separation doesn’t mean geographic withdrawal. We reject monasticism’s escape from society. Instead, “not of the world” means refusing to adopt worldly values, appetites, and ultimate loyalties.

Consider Daniel in Babylon. He served in a pagan government, advised foreign kings, and engaged political structures—yet maintained covenant faithfulness, even unto the lions’ den. Joseph likewise rose to Egypt’s second-highest office without moral compromise. Both men demonstrate cultural involvement needn’t mean spiritual capitulation.

Paul puts it clearly: “Set your minds on things above, not on things that are on earth” (Colossians 3:2). The separation is vertical, not horizontal.

Reformed theology helps us understand why this matters. Total depravity means the world-system is comprehensively corrupted by sin. Every cultural institution, philosophy, and value system bears the mark of the fall. Yet common grace means God’s goodness still permeates creation. There’s a fundamental antithesis—a spiritual division between the kingdom of light and the kingdom of darkness (2 Corinthians 6:14-18).

Practically, this means Christians reject the world’s definitions of success, morality, identity, and purpose. We live by different metrics, serve different masters, and pursue different goals—even while our neighbours pursue theirs.

WHAT “IN THE WORLD” REQUIRES

But Jesus explicitly prays that his Father not remove us from the world. Why? Because we’re sent with purpose. “As you sent me into the world, so I have sent them into the world” (John 17:18).

- The incarnation itself is our model. Jesus entered the world redemptively—not to condemn it, but to save it. We are salt and light (Matthew 5:13-16), metaphors requiring contact to be effective. Salt in the shaker preserves nothing; light under a basket illuminates nothing.

- Genesis 1:28 encourages us to take our cultural mandate seriously: God’s command to fill and subdue the earth remains in effect. Abraham Kuyper famously declared, “There is not a square inch in the whole domain of our human existence over which Christ, who is Sovereign over all, does not cry, ‘Mine!'” Cultural engagement isn’t optional—it’s worship when done as Scripture mandates it.

- Scripture models this engagement beautifully. Paul reasoned with Athenian philosophers (Acts 17), becoming “all things to all people” to win some (1 Corinthians 9:22). Jeremiah commanded exiled Israelites to “seek the welfare of the city where I have sent you into exile” (Jeremiah 29:7).

- Withdrawal from the world isn’t an option. It contradicts the Great Commission (Matthew 28:19-20). Isolation prevents witness. We cannot make disciples from a distance.

HOLDING THE TENSION

So how do we maintain this balance? Ask diagnostic questions: Is the world shaping my desires, or am I shaping the world through godly influence? Am I compromising biblical conviction for cultural acceptance? Am I using my presence redemptively?

Peter calls us “sojourners and exiles” who maintain “good conduct among the Gentiles” (1 Peter 2:11-12). James defines pure religion as keeping “oneself unstained from the world” (James 1:27). We exercise Christian liberty while examining our consciences (1 Corinthians 10:23-33).

THE GRACE-FILLED BALANCE

The Reformed answer to our opening tension is neither escapism nor accommodation. It’s consecrated engagement under Christ’s lordship. Jesus prays for our sanctification in the world (John 17:17), not apart from it.

We live as holy aliens whose distinctive lives point others to Christ. This balanced posture is possible only through sanctifying grace and Spirit-empowerment. Our encouragement? “He who is in you is greater than he who is in the world” (1 John 4:4).

We’re pilgrims passing through, yes—but pilgrims on mission, transforming every place our feet touch for the glory of our King.

IN THE WORLD BUT NOT OF IT: RELATED FAQs

What is Luther’s “two kingdoms” doctrine and how does it help us understand being in but not of the world? Martin Luther taught God governs through two distinct kingdoms: the spiritual kingdom (the church, governed by the gospel) and the earthly kingdom (civil government, governed by law and reason). This doesn’t mean Christians live schizophrenic lives. Rather, we serve God differently in each sphere—the church proclaims Christ and administers sacraments, while civil authorities maintain order and justice. Luther’s insight helps us engage politics, business, and culture without expecting these institutions to function like the church. Simultaneously, it cautions the church against wielding the sword that belongs to civil authorities. This framework prevents both theocracy and complete Christian withdrawal from public life.

- How does Calvin’s doctrine of vocation challenge the idea of separating from the world? John Calvin taught all legitimate work—not just church ministry—is a sacred calling before God. Whether you’re a farmer, merchant, magistrate, or mother, you’re fulfilling a divine vocation that glorifies God and serves your neighbour when done faithfully. This doctrine dismantled the medieval hierarchy that elevated monks and priests above “ordinary” Christians, declaring instead that changing diapers can be just as holy as celebrating communion if done in obedience to God’s call. Calvin’s vision means Christians should be the most engaged citizens, workers, and culture-makers, bringing excellence and integrity to every corner of society as acts of worship.

- What is Kuyper’s transformationalism? How does it differ from other approaches to culture? Abraham Kuyper, the Dutch theologian and Prime Minister, articulated a vision called “transformationalism”—the belief that Christians should actively work to redeem and restore culture, not just evangelise individuals or withdraw into holy huddles. His famous declaration that Christ claims sovereignty over “every square inch” of reality meant Christians should bring biblical principles into art, science, politics, education, and economics. Unlike approaches that simply condemn culture or passively accommodate it, Kuyper’s transformationalism calls believers to be culture-makers who create distinctly Christian alternatives in every sphere. This is why the Reformed tradition has historically produced not just pastors, but also groundbreaking artists, scientists, politicians, and entrepreneurs.

Did the early church fathers address this tension between being in and not of the world? The early church wrestled profoundly with this question, often in life-or-death circumstances. The second-century Epistle to Diognetus (author unknown) beautifully captures the paradox: “Christians are indistinguishable from other men in country, language or customs… yet they display the remarkable and admittedly extraordinary constitution of their own citizenship.” Church fathers like Augustine distinguished between the “City of God” and the “City of Man”: Christians are pilgrims whose ultimate loyalty transcends earthly kingdoms. However, these same fathers often disagreed on specifics—some like Tertullian leaned toward separation (“What has Athens to do with Jerusalem?”), while others like Justin Martyr engaged Greek philosophy extensively, seeing truth wherever God had planted it.

- How are we to view entertainment, social media, and popular culture? Reformed theology rejects both legalism (blanket prohibitions) and libertinism (uncritical consumption), applying instead the principle of Christian liberty with discernment. The question isn’t whether Christians can watch movies or use Instagram, but whether these activities are edifying, God-glorifying, and serving our sanctification rather than our sinful nature. Jonathan Edwards’ test remains helpful: does this practice increase my appetite for God or decrease it? Reformed believers engage culture critically and selectively—enjoying the good gifts of common grace while rejecting content that celebrates sin, distorts truth, or captures our hearts with unworthy affections.

- How does the Anabaptist approach to engaging the world differ from the Reformed view? While both traditions take “not of the world” seriously, they differ significantly on cultural engagement. Historic Anabaptist communities (like the Amish and some Mennonites) have often emphasised separation, forming distinct counter-cultural communities with limited participation in worldly institutions like military service or political office. The Reformed tradition, by contrast, has emphasised active participation in all legitimate spheres of society, believing Christians should be the best citizens, magistrates, and cultural contributors. Both traditions agree on spiritual distinctiveness, but disagree on whether that distinctiveness requires social separation or active cultural transformation—the Anabaptists tend toward the former, the Reformed toward the latter.

How should Christians respond when engaging the world requires interacting with non-Christian ideas or practices? Theologian Herman Bavinck taught that “all truth is God’s truth”—meaning Christians can recognise wisdom, beauty, and insight even in pagan or secular sources because common grace ensures God’s fingerprints remain on his creation. Paul himself quoted pagan poets in Acts 17, and Joseph and Daniel served pagan kings. The key is discernment: we can learn from secular psychology, appreciate non-Christian art, or work in companies with non-believing colleagues without adopting their ultimate worldview. Think of it as “plundering the Egyptians” (Exodus 12:35-36)—taking what is valuable while rejecting what contradicts Scripture, always filtering everything through the lens of biblical truth and maintaining our primary allegiance to Christ above all competing claims.

IN THE WORLD BUT NOT OF IT: OUR RELATED POSTS

Editor's Pick

The Throne-Room Vision: Who Did Isaiah See?

The scene is unforgettable: Isaiah stands in the temple, and suddenly the veil between heaven and earth tears open. He [...]

The Angel of the Lord: Can We Be Certain It Was Christ All Along?

Throughout the Old Testament, a mysterious figure appears: the Angel of the LORD. He speaks as God, bears God’s name, [...]

SUPPORT US:

Feel the Holy Spirit's gentle nudge to partner with us?

Donate Online:

Account Name: TRUTHS TO DIE FOR FOUNDATION

Account Number: 10243565459

Bank IFSC: IDFB0043391

Bank Name: IDFC FIRST BANK