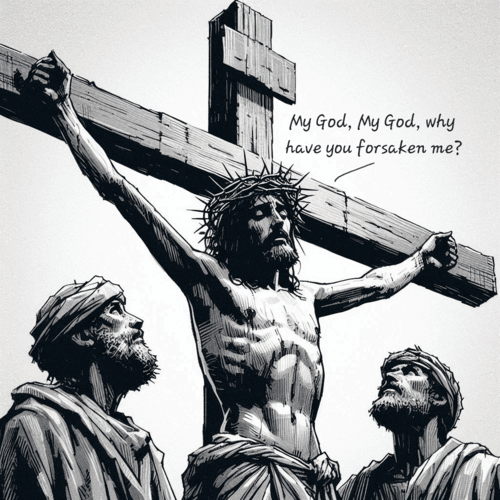

Why Does Jesus Cry, ‘My God My God’?

FROM OUR SERIES ON CHRIST’S SEVEN FINAL UTTERANCES FROM THE CROSS

Of all the words Jesus spoke from the cross, none perhaps, are more jarring than His anguished cry: “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me?” These words, recorded in Matthew 27:46 and Mark 15:34, have caused both believers and sceptics to pause and wonder. How could Jesus, whom Christians believe to be God incarnate, be forsaken by God? What does this moment of apparent abandonment mean for our understanding of salvation?

QUOTING A PSALM IN DARKNESS

First, we need to recognise Jesus wasn’t simply expressing spontaneous despair. He was quoting the opening line of Psalm 22, a practice common among Jews who’d reference an entire psalm by citing its first words. This psalm begins in anguish but ends in triumph—moving from “Why have you forsaken me?” to “He has done it!”

Jesus, even in his moment of greatest suffering, was placing Himself within the grand narrative of Scripture. By invoking Psalm 22, He identifies Himself as the ultimate fulfillment of this prophetic lament, pointing both to His current agony and to the victory that would follow.

WHAT “FORSAKEN” REALLY MEANS

When Jesus cried out about being forsaken, He wasn’t suggesting the Trinity had been broken or that His divine nature had somehow been separated from the Father. Rather, in Reformed theology, this moment represents the Father turning away from the Son as Jesus bore the full weight of human sin.

To be “forsaken” in this context means Jesus experienced the withdrawal of the Father’s fellowship and favour. For the first and only time in all eternity, the perfect communion between Father and Son was interrupted—not because their essential relationship changed, but because Jesus had taken our sin upon himself.

THE NECESSARY SACRIFICE

From a Reformed perspective, this forsaking was absolutely necessary for our salvation. God’s justice demands that sin be punished. His holiness cannot simply overlook our rebellion. At the cross, we see both God’s justice and love displayed in perfect harmony.

As our substitute, Jesus didn’t just suffer physical pain—He endured the spiritual agony of bearing God’s righteous judgement against sin. The Father’s “forsaking” of the Son was the pouring out of divine wrath that we deserved. In that dark moment, Jesus experienced the hell that was rightly ours.

This substitutionary atonement stands at the heart of Reformed theology. Jesus wasn’t merely setting an example or demonstrating God’s love (though he was doing both). He was actively bearing our punishment, satisfying divine justice, and reconciling us to God.

BEYOND PHYSICAL SUFFERING

The cry reveals Jesus’s suffering went far beyond the physical tortures of crucifixion. While the nails and thorns inflicted terrible bodily pain, His spiritual agony was immeasurably worse.

We cannot fully comprehend what it meant for the eternally beloved Son to experience the Father’s face turned away. For Jesus, who had lived in perfect communion with the Father throughout eternity, this relational rupture represented suffering beyond our imagination.

Isaiah 53:10 tells us “it was the Lord’s will to crush him and cause him to suffer.” This was not divine child abuse, as some critics suggest, but rather the outworking of the Trinitarian plan of redemption—a plan the Son willingly embraced.

COMMON MISUNDERSTANDINGS

Some suggest Jesus only felt abandoned but wasn’t actually forsaken. Others claim the cry indicates failure or doubt in Jesus’ mission. Both miss the mark. Jesus wasn’t confused or mistaken—He was experiencing exactly what he came to experience: the judgement for our sin.

Neither did the Father stop loving the Son in this moment. Rather, their love for each other and for us was demonstrated precisely in their willingness to endure this temporary separation for our sake.

Jesus’ cry wasn’t a lapse of faith but the opposite—the fulfillment of His faithful mission to bear our sins. He remained perfectly obedient even while experiencing the consequences of our disobedience.

THE COMFORT IN THE CRY

There’s profound pastoral comfort in Jesus’ words. When we feel abandoned by God in our darkest moments, we can remember Jesus experienced the ultimate abandonment so we would never have to. As He promises elsewhere, “Never will I leave you; never will I forsake you” (Hebrews 13:5).

Jesus was forsaken so we could be accepted. He experienced God’s face turned away so we might forever see God’s face turned toward us in love. The darkness He endured secured the unshakable light of our salvation.

CONCLUSION: MY GOD, MY GOD

Jesus’ cry of dereliction represents the most profound paradox in history: the moment when God was most glorified was the moment when His Son experienced divine abandonment. The darkest moment in history secured our brightest hope.

In those haunting words from the cross, we hear both the terrible reality of our sin and the immeasurable depth of divine love. Jesus’ question—”Why have you forsaken me?”—finds its answer in us. He was forsaken for our sake, abandoned so we might be embraced.

This is the heart of the gospel from a Reformed perspective: at the cross, Jesus took what we deserved (abandonment) so we might receive what He deserved (acceptance). His cry is, paradoxically, our assurance that we will never be forsaken.

In the end, Jesus’ cry doesn’t diminish His divinity—it magnifies the wonder of His love. It doesn’t raise questions about God’s goodness—it provides the ultimate answer to them. And it doesn’t represent defeat, but the pathway to the greatest victory the world has ever known.

MY GOD, MY GOD: RELATED FAQs

Did Jesus quote the entire Psalm 22 from the cross? While the Gospels only record Jesus citing the first verse, some scholars believe He may have been meditating on the entire psalm. The psalm’s trajectory from suffering to victory mirrors Jesus’ crucifixion and resurrection. Several details in the psalm eerily foreshadow specific aspects of the crucifixion, including mockers, pierced hands and feet, and divided garments.

- How did early church fathers interpret Jesus’ cry? Church fathers such as Augustine and Athanasius viewed the cry as Jesus speaking representatively as the head of His body (the church). They emphasised Christ spoke these words not out of personal despair but as the voice of humanity in our sinful condition. This understanding preserves both the reality of Christ’s suffering and the unity of the Trinity throughout the crucifixion.

- Was Jesus experiencing “spiritual death” on the cross? Jesus experienced the judicial consequences of sin—separation from God’s fellowship—but not “spiritual death” in the sense of becoming spiritually corrupted or losing His divine nature. His perfect holiness remained intact even while bearing sin’s penalty. This distinction is important because Jesus conquered death precisely because death had no legitimate claim on him.

- Did the Father actually turn away from the Son? Reformed theology typically describes this as a judicial act rather than an emotional rejection. The Father’s love for the Son never diminished, but justice required the penalty for sin to be fully executed. It’s better understood as the Father delivering up the Son to judgement rather than emotionally abandoning Him.

- How would Jewish witnesses have understood Jesus’ words? Jewish bystanders familiar with the psalms would have recognised the reference to Psalm 22 immediately. Some may have made the connection to the psalm’s triumphant ending and messianic overtones. Others likely saw it as confirmation that Jesus was indeed abandoned by God and thus discredited as Messiah.

- Why did Jesus address God as “My God” rather than “My Father” in this moment? The shift from Jesus’s typical intimate address of “Father” to the more formal “My God” reflects the judicial nature of what was happening. In this moment, Jesus stood before God as mankind’s representative under judgement. Yet Jesus still says “My God,” maintaining His claim of personal relationship even in the midst of bearing divine wrath.

How does Jesus’ cry relate to believers’ experiences of God’s “absence”? Christians throughout history have experienced what mystics call “the dark night of the soul”—times when God seems absent or silent. Jesus’ cry validates these experiences as real while also transforming them. Because Jesus endured ultimate abandonment, believers can trust their experiences of God’s seeming absence are temporary and will ultimately give way to deeper communion.

MY GOD, MY GOD: OUR RELATED POSTS

- Father, Forgive Them: Who Was Jesus Praying For?

- ‘Today You Will Be With Me in Paradise’: What Did Jesus Mean?

- ‘Behold Your Mother’: Why Does Jesus Entrust Mary to John?

- John 19:28: Why Did Jesus Say ‘I Thirst’?

- It is Finished”: What Does Jesus Mean?

- Last Words on the Cross: Into Your Hands I Commit My Spirit

Editor's Pick

The Throne-Room Vision: Who Did Isaiah See?

The scene is unforgettable: Isaiah stands in the temple, and suddenly the veil between heaven and earth tears open. He [...]

The Angel of the Lord: Can We Be Certain It Was Christ All Along?

Throughout the Old Testament, a mysterious figure appears: the Angel of the LORD. He speaks as God, bears God’s name, [...]

SUPPORT US:

Feel the Holy Spirit's gentle nudge to partner with us?

Donate Online:

Account Name: TRUTHS TO DIE FOR FOUNDATION

Account Number: 10243565459

Bank IFSC: IDFB0043391

Bank Name: IDFC FIRST BANK