Does God Change His Mind? The Truth About Genesis 6:6

Genesis 6:6 stops many Bible readers in their tracks: “And the LORD regretted that he had made man on the earth, and it grieved him to his heart.” Wait—God regretted creating humanity? Did the all-knowing God make a mistake? Did He change His mind?

This verse genuinely puzzles thoughtful Christians, and understandably so. It sounds like God looked at His creation, realised things had gone wrong, and wished He could take it all back. But the Reformed tradition offers a compelling answer rooted in Scripture itself: this is anthropopathism—God graciously accommodating His language to our finite understanding.

God experiences no change of mind, yet Scripture uses human terms to describe His unchanging purposes… just as He has no physical “arm” though the Bible speaks often of “arm of the LORD” (Exodus 15:16),

GOD DOES NOT CHANGE: SCRIPTURE’S CLEAR TEACHING

Before we interpret difficult passages, we must establish what Scripture plainly teaches. The Bible is emphatic about God’s immutability—His unchanging nature:

- Numbers 23:19 declares: “God is not man, that he should lie, or a son of man, that he should change his mind.”

- 1 Samuel 15:29 states: “The Glory of Israel will not lie or have regret, for he is not a man, that he should have regret.”

- Malachi 3:6 affirms: “For I the LORD do not change.”

- James 1:17 describes God as “the Father of lights, with whom there is no variation or shadow due to change.”

- Psalm 102:25-27 contrasts creation’s transience with God’s eternality: the heavens will perish and wear out “like a garment,” but “you are the same, and your years have no end.”

These texts establish God’s immutability as a foundational divine attribute—something that distinguishes the Creator from every creature. This isn’t obscure theology; it’s what Scripture repeatedly, clearly teaches.

THE PRINCIPLE OF ANTHROPOPATHISM

Here’s where the solution emerges. Scripture regularly describes God using human terms—body parts, emotions, psychological states—so that finite creatures can understand infinite realities. Consider God’s “arm”:

- Exodus 15:16 celebrates “the greatness of your arm”

- Isaiah 53:1 asks “to whom has the arm of the LORD been revealed?”

- Isaiah 59:16 says “his own arm brought him salvation”

No Christian believes God is literally physical with biceps and elbows. “Arm” signifies God’s power in action. We instinctively understand this is accommodated language—God condescending to speak in human terms.

The same principle applies throughout Scripture. God has “eyes” (2 Chronicles 16:9) and “ears” (Psalm 34:15), though He’s pure spirit. God “remembers” His covenant (Genesis 9:15-16), though He never forgets. As John Calvin observed, God “lisps” to us like a nursemaid to infants, using our language because we cannot comprehend His essence directly.

The same principle applies to God’s emotions and mental states. When Scripture says God “repents” or “regrets,” it describes how God’s actions appear from our human perspective within time, not a literal change in His eternal, unchanging decree.

GENESIS 6:6 IN PERSPECTIVE

With this framework, Genesis 6:6 makes perfect sense. The verse expresses the reality of God’s grief over human sin—His holy, burning opposition to the wickedness that filled the earth. It describes God’s subsequent actions (the Flood) in terms we understand: “If I made this, now I must unmake it.”

But God’s eternal plan always included creating humanity, judging a wicked generation through the Flood, and preserving Noah to start fresh. Nothing surprised God. Nothing forced a revision of His plans.

The clearest proof? 1 Samuel 15. In verse 11, God says “I regret that I have made Saul king.” Yet verse 29—in the same chapter—declares God “will not lie or have regret, for he is not a man, that he should have regret.” Both statements in the same narrative! One uses anthropopathism to describe God’s actions; the other states literal truth about His nature. The biblical authors knew exactly what they were doing.

THE POSITIVE MEANING OF “GOD REPENTED”

This language isn’t empty metaphor—it reveals profound truths about God’s character and His relationship with us.

- First, it reveals God’s holy hatred of sin and the real pain human rebellion causes our covenant Lord. The grief is genuine. Israel’s unfaithfulness “grieved him to his heart” (Psalm 78:40). Believers can “grieve the Holy Spirit” (Ephesians 4:30). God’s emotional response to sin is real and relational, not pretended or theatrical.

- Second, it magnifies grace. The same Hebrew verb (nacham) describes God “relenting” from announced judgment when people genuinely repent. When Nineveh repented, “God relented of the disaster that he had said he would do to them” (Jonah 3:10). Joel 2:13-14 urges Israel to return to God “for he is gracious and merciful…and relents over disaster.”

Herman Bavinck explains this: “Repentance in God is not a change of purpose but a change in the way He realises His purpose when new factors (human responses) enter the relationship” (Reformed Dogmatics, Vol. 2, p. 158). God’s grief is real relational sorrow, not surprise or Plan-B regret.

ANSWERING OBJECTIONS

“But doesn’t this make God deceive us?” Not at all—it makes God communicate with us. When Jesus says “I am the door” (John 10:9), He’s not made of wood. Figurative language isn’t deceptive; it’s how language works. Scripture itself teaches us to read repentance texts through the lens of immutability texts.

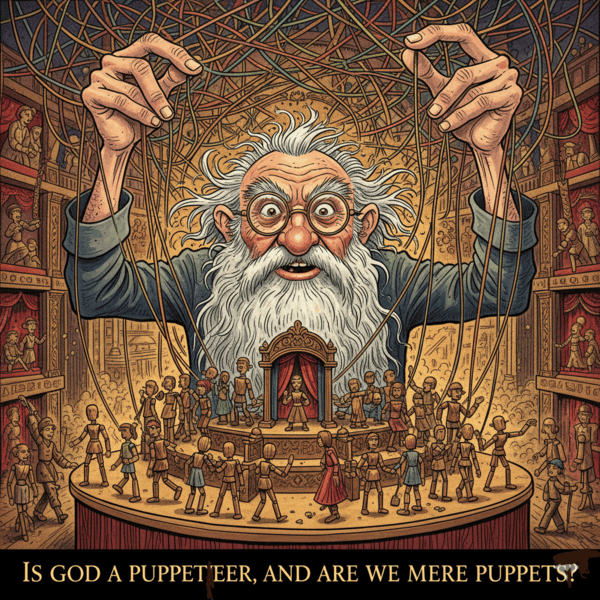

“Open Theism says God really does change His mind.” Yes, and Open Theism directly contradicts Numbers 23:19 and 1 Samuel 15:29. It solves one interpretive challenge by creating far worse problems: undermining biblical prophecy, God’s exhaustive foreknowledge, and the absolute security of His promises.

“Isn’t this just theological gymnastics?” No—it’s basic biblical interpretation. We already recognise anthropomorphism with God’s “arm,” “eyes,” and “sitting” on a throne. Recognising anthropopathism simply extends the same principle to emotions and mental states, honouring Scripture’s own teaching about God’s unchanging nature.

WHY THIS MATTERS

This isn’t abstract theology. God’s immutability provides rock-solid pastoral comfort. When God promises salvation, election, or eternal life, He cannot change His mind (Romans 11:29: “the gifts and calling of God are irrevocable”). Your security doesn’t depend on God’s mood or new information—it rests on His unchanging character and eternal purpose.

Genesis 6:6 uses the language of human grief to help finite creatures understand the infinite God’s holy response to sin. The Reformed tradition honours both mysteries: God’s transcendence (He never changes) and His condescension (He speaks our language). Trust the unchanging God who graciously stoops to communicate with His beloved children.

RELATED FAQs

What do modern Reformed scholars say about divine impassibility and God’s emotions? Contemporary Reformed theologians like Michael Horton and Scott Oliphint affirm God experiences real emotions while maintaining His immutability and impassibility properly understood. They distinguish between God being affected by creatures in a way that changes His essence or purposes (which cannot happen) versus God genuinely responding emotionally to His creatures according to His eternal nature. John Frame argues God’s emotions are archetypal—the original reality of which human emotions are creaturely copies. God’s grief over sin is more real than ours, not less, but it flows from His unchanging holy character rather than from unexpected circumstances altering His plans.

- How does the Hebrew word nacham help us understand what’s happening in Genesis 6:6? The Hebrew verb nacham has a semantic range including “to be sorry,” “to regret,” “to relent,” “to comfort oneself,” and “to change one’s mind about a course of action.” Bruce Waltke notes this verb often appears in covenantal contexts where God’s relational response to human behavior is in view. The word emphasises the relational and emotional dimension of God’s response rather than implying ontological change. Significantly, the same root gives us the name “Noah” (Noach)—“comfort” or “rest”—suggesting wordplay: God grieves over humanity’s sin but will find “rest” in preserving the righteous remnant.

- Did any of the church fathers address this question, and what did they say? Augustine addressed this extensively in The City of God and Against Lying, arguing that God’s “repentance” refers to the change in things God has decreed, not a change in God Himself. John Chrysostom, in his homilies on Genesis, insisted that such language demonstrates God’s “condescension” (synkatabasis)—His gracious accommodation to human weakness. Tertullian wrestled with this in Against Marcion, using it to defend God’s justice and mercy as consistent attributes rather than competing divine personalities. The consensus across East and West was clear: these texts describe God’s actions in human terms, not changes in His eternal will.

What about Jeremiah 18:7-10, where God explicitly says He will change His announced plans? Jeremiah 18:7-10 is actually the key to understanding divine “repentance” properly—God declares His sovereign principle that announced blessings or curses are conditional on human response within the covenant relationship. Reformed theologian Geerhardus Vos explained this as God’s “covenant administration”: the unchanging God implements His eternal purpose through real covenant dynamics where human choices matter genuinely. God’s warning of judgement or promise of blessing functions as His ordained means of bringing about repentance or confirming rebellion—the outcome was eternally purposed, but human beings experience it as genuine relational interaction. This isn’t arbitrary divine mood swings; it’s the consistent outworking of God’s unchanging covenant character.

- How does this relate to prayer—if God doesn’t change, why pray? God’s immutability doesn’t make prayer pointless; it makes prayer meaningful within God’s eternal plan. Reformed theology affirms that God has eternally decreed both ends and means—He ordains that certain outcomes will occur through the prayers of His people. J.I. Packer notes that prayer doesn’t inform God of new facts or twist His arm, but it aligns us with His purposes and serves as the appointed means by which He accomplishes His will. When God “relents” in response to prayer (Exodus 32:14), He’s fulfilling His eternal purpose through the very prayers He ordained—Moses’ intercession was part of God’s plan, not a surprise that changed it.

- Does this mean the Incarnation didn’t involve real change for God? The Incarnation involves the Second Person of the Trinity assuming a human nature in addition to His divine nature, not a transformation of His divine essence. Reformed Christology (following Chalcedon) affirms Christ has two natures—fully divine and fully human—in one person without mixture, confusion, or conversion of one into the other. The divine nature remains immutable; the human nature experiences growth, learning, suffering, and death. As the Westminster Confession states (8.2), Christ remained “the same in substance, equal with the Father” even while becoming “man, of a reasonable soul and body.” So the Incarnation involves the Son taking on what He didn’t have before (humanity), but not ceasing to be what He eternally is (God).

What’s the pastoral danger of Open Theism’s view that God literally changes His mind? If God literally doesn’t know the future and changes His plans based on new information, then no divine promise can be absolutely certain. Our salvation, God’s promises about Christ’s return, and every prophetic word become contingent on future unknowns even to God Himself. Greg Boyd and other Open Theists try to preserve confidence in God’s “general” plans, but this offers cold comfort—how do we know our specific situation isn’t one where God’s Plan A fails and He needs a Plan B? The God who says “I the LORD do not change; therefore you, O children of Jacob, are not consumed” (Malachi 3:6) links His immutability directly to the security of His people. Reformed theology preserves both God’s genuine emotional responses and the absolute reliability of His promises.

OUR RELATED POSTS

Editor's Pick

Why Do People Hate the Doctrine of Election?

…WHEN THEY REALLY SHOULDN’T Few Bible doctrines provoke stronger reactions than election. The idea that God chose some for salvation [...]

The Doctrine of Providence: Does God Really Govern All Things?

You’re sitting in the doctor’s office when the diagnosis lands like a thunderclap. Your mind races: Why this? Why now? [...]

No Decay, No Defeat: What It Means That Christ’s Body Saw No Corruption

On the Day of Pentecost, Peter stood before thousands and made a startling claim: David's body decayed in the tomb, [...]

SUPPORT US:

Feel the Holy Spirit's gentle nudge to partner with us?

Donate Online:

Account Name: TRUTHS TO DIE FOR FOUNDATION

Account Number: 10243565459

Bank IFSC: IDFB0043391

Bank Name: IDFC FIRST BANK