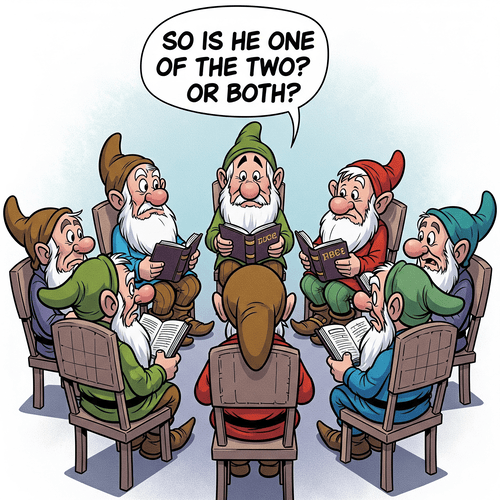

Jesus as Son of God and Son of Man: How are the Titles Different?

When Jesus walked among us, He claimed two remarkable titles that have puzzled and inspired believers for two millennia: Son of God and Son of Man. To modern ears, the title may sound contradictory—how can someone be both divine and human? Yet the titles, far from being theological riddles, reveal the profound mystery at the heart of Christian faith. Understanding their differences unlocks the wonder of the Incarnation and explains why Jesus alone can save.

SON OF GOD: THE DIVINE TITLE

The title “Son of God” thunders with divine authority throughout Scripture. When Peter declared, “You are the Christ, the Son of the living God” (Matthew 16:16), Jesus didn’t correct him—He blessed him. This wasn’t merely honorific language; it was a declaration of essential deity.

The Old Testament prepared us for this revelation. Psalm 2:7 records God’s decree: “You are my Son; today I have begotten you.” In 2 Samuel 7:14, God promises David that his ultimate heir would be His Son. These weren’t merely predictions of a special human being, but glimpses of the eternal relationship within the Trinity itself.

Revealing Eternal Generation: Reformed theology, grounded in Scripture and crystallised in confessions like Westminster, teaches us “Son of God” reveals Christ’s eternal generation—His timeless relationship with the Father. This isn’t about chronological beginning but eternal being. The Son shares the same divine essence (homoousios) as the Father, possessing all divine attributes: omnipotence, omniscience, omnipresence, and immutability.

This title reveals staggering truths. As Son of God, Jesus has authority to forgive sins (Mark 2:10), a prerogative belonging to God alone. He accepts worship (Matthew 14:33), commands angels (Matthew 26:53), and claims equality with the Father (John 10:30). The Father Himself testifies to this relationship at Jesus’ baptism and transfiguration: “This is my beloved Son” (Matthew 3:17, 17:5).

SON OF MAN: THE HUMAN AND MESSIANIC TITLE

“Son of Man” initially sounds like it emphasises Jesus’ humanity—and it does—but its roots run deeper into messianic prophecy. Daniel 7:13-14 presents a vision of “one like a son of man” receiving eternal dominion from the Ancient of Days. This figure is both human and transcendent, both accessible and authoritative.

Jesus used this title for Himself more than any other—over 80 times in the Gospels. Through it, He claimed the messianic identity while emphasising His genuine humanity. Unlike the title “Son of God,” which the demons readily acknowledged, “Son of Man” required spiritual insight to understand.

Reformed theology recognises the title reveals Christ’s complete human nature. He wasn’t merely God appearing human (Docetism) or God temporarily inhabiting a human body (Apollinarianism). Jesus possessed a rational soul and true body, experiencing genuine human emotions, physical limitations, and moral testing—yet without sin.

As Son of Man, Jesus serves as the second Adam, representing humanity before God. Where the first Adam failed through disobedience, the Son of Man succeeds through perfect obedience. This representative role makes Him uniquely qualified to be our mediator, understanding our weaknesses while maintaining moral perfection (Hebrews 4:15).

HOW THEY DIFFER: CRUCIAL DISTINCTIONS

The differences between the titles illuminate the richness of Christ’s person and work.

- Nature Emphasised: “Son of God” spotlights Christ’s divine nature and eternal existence, while “Son of Man” highlights His human nature and temporal mission. The first speaks of His eternal generation; the second of His incarnation in time.

- Relational Focus: As Son of God, Jesus relates primarily to the Father within the Trinity’s eternal fellowship. As Son of Man, He relates to humanity as our representative and substitute.

- Soteriological Function: The Son of God possesses the power to save—only God can conquer sin, death, and Satan. The Son of Man has the ability to save—only a true human can represent humanity and suffer in our place. Both are necessary; neither is sufficient alone.

- Authority Structure: Divine authority flows from Christ’s essential deity as Son of God. Messianic authority comes through His obedient humanity as Son of Man. He rules both as eternal King and as the Suffering Servant exalted through humility.

The Chalcedonian Definition (451 AD), embraced by Reformed theology, maintains these distinctions without division: two natures in one person, without confusion, change, division, or separation. Each title emphasises one nature without negating the other.

HOW THEY ARE ALIKE: ESSENTIAL UNITY

Despite their differences, the titles share crucial similarities that underscore the unity of Christ’s person.

Both refer to the same individual—not two separate beings but one Christ. The hypostatic union means that everything Jesus did, He did as one person possessing two natures. When He wept, the eternal Son wept; when He stilled storms, the Son of Man commanded nature.

Both titles involve authority, though expressed differently. Divine authority belongs to the Son of God by right; messianic authority is earned by the Son of Man through obedience. Yet both flow from the same person, creating perfect harmony between divine sovereignty and human responsibility.

Most importantly, both titles are essential for salvation. Only the divine Son of God could satisfy infinite justice and overcome death itself. Only the human Son of Man could represent us, obey in our place, and suffer the penalty we deserved. Remove either nature, and redemption becomes impossible.

THE REFORMED CONFIDENCE

Reformed theology insists on both titles because Scripture presents both. We don’t minimise Christ’s humanity to protect His divinity, nor diminish His divinity to make His humanity more palatable. The God-man is the unique bridge between heaven and earth, the only mediator qualified by nature to reconcile holy God with sinful humanity.

This understanding transforms Christian living. We worship the majestic Son of God while finding comfort in the sympathetic Son of Man. We trust His divine power while relating to His human experience. In prayer, we approach the throne of the almighty God through the intercession of one who knows our frame.

The titles “Son of God” and “Son of Man” don’t compete—they complete. Together, they reveal the magnificent mystery of the Incarnation: the eternal Word became flesh, divine love took human form, and heaven touched earth. In Jesus Christ, we discover not a riddle to solve but a Saviour to embrace, fully God and fully man, uniquely qualified to bring us home.

JESUS AS SON OF GOD AND SON OF MAN: RELATED FAQs

Why didn’t Jesus use “Son of God” to describe Himself as often as “Son of Man”? Jesus strategically chose “Son of Man” as His preferred self-designation because it required spiritual discernment to understand its full meaning, while “Son of God” could easily be misunderstood in political terms. The Jewish leaders were looking for a conquering Messiah, and openly claiming divine sonship too early might have derailed His mission before the cross. Contemporary Reformed scholar Michael Horton notes that Jesus revealed His identity progressively, allowing His works to authenticate His words.

- How do modern Reformed theologians view these titles today? Modern Reformed scholars emphasise both titles demonstrate what John Frame calls “perspectivalism”—different angles on the same glorious truth. Michael Horton stresses “Son of Man” particularly highlights Jesus’ role as the last Adam, while “Son of God” emphasises His eternal relationship within the Trinity. Kevin Vanhoozer adds these titles show how Jesus is both the subject and object of redemption—saving as God, representing as man.

- Does “Son of Man” ever refer to Jesus’ divine nature, or only His humanity? While “Son of Man” primarily emphasises Jesus’ humanity, it carries divine implications, especially from Daniel 7 where this figure receives eternal dominion and universal worship. Reformed scholar Herman Bavinck argued the title shows Jesus as the God-man, not merely man. The “Son of Man” who forgives sins, walks on water, and will return in glory clearly transcends ordinary humanity while remaining genuinely human.

How do these titles relate to the covenant of redemption between the Father and Son? Reformed theology teaches that before creation, the Father and Son entered a covenant where the Son agreed to become incarnate and redeem the elect. The title “Son of God” reflects His eternal covenant partner status, while “Son of Man” shows His covenant fulfillment role. Westminster Seminary’s Lane Tipton explains that both titles demonstrate different aspects of Christ’s mediatorial work—divine authority to accomplish salvation and human ability to represent the covenant people.

- Why don’t we see “Son of God” used as much in the Old Testament compared to “Son of Man” imagery? The Old Testament prepared for the Son of God revelation more subtly because Israel wasn’t ready for explicit Trinitarian doctrine. While we see hints in Psalm 2 and 2 Samuel 7, the full revelation awaited the incarnation. Conversely, “Son of Man” language in Daniel and Ezekiel provided clearer messianic expectation. Reformed scholar Geerhardus Vos argued progressive revelation meant some truths had to wait for their proper historical moment—the incarnation was that moment for fully understanding divine sonship.

- How do these titles help us understand Jesus’ prayers to the Father? When Jesus prays, He does so as the incarnate Son—both divine Son relating to His Father and human Son depending on divine strength. The “Son of Man” aspect explains why Jesus needed to pray (genuine human dependence), while the “Son of God” aspect explains the intimate access and confidence in His prayers. Contemporary Reformed theologian Todd Billings emphasises that Jesus’ prayers show us both divine communion within the Trinity and the model of human dependence on God.

What about the apparent contradiction when Jesus asks “Why have you forsaken me?” on the cross? This cry doesn’t contradict Jesus’ divine sonship but demonstrates the mystery of the incarnation. As “Son of Man,” Jesus genuinely experienced forsakenness and the weight of sin’s curse, while as “Son of God,” the Trinity remained unbroken (God cannot be separated from Himself). Reformed scholars like John Murray explain this as the divine Son experiencing human forsakenness in His human nature while maintaining eternal fellowship in His divine nature. The cry shows the depth of His substitutionary suffering, not a breakdown in divine relationship.

JESUS AS SON OF GOD AND SON OF MAN: OUR RELATED POSTS

- 1 John 5:6: How Do Water and Blood Reveal Jesus’ True Identity

- Why do We Affirm Jesus is Fully God and Fully Man?

- The Virgin Birth: Why Do We Affirm It?

- Stop the Search: Jesus is The Promised Messiah

- Exploring the Historicity of Jesus: Facts and Evidence

- Five Eyewitnesses of the Resurrection: Their Compelling Testimony

- Types of Christ and His Cross in the Old Testament

Editor’s Pick

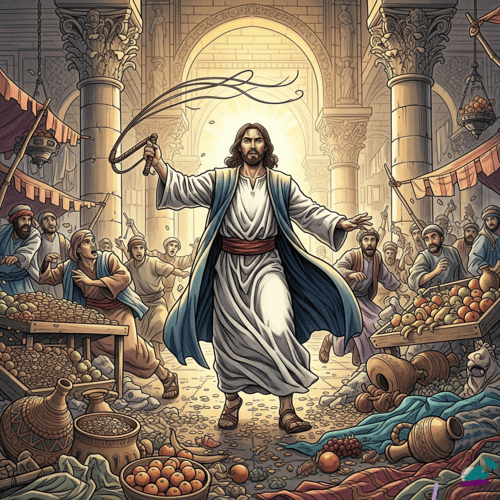

Sacred Fury: What Christ’s Temple Cleansing Truly Means

Mark 11 records the crack of a handmade whip that echoed through the temple corridors. Tables crashed to the ground, [...]

Did Jesus Cleanse the Temple Twice?

OR DID JOHN DISAGREE WITH THE SYNOPTICS ON TIMING? One of sceptics’ favourite "gotcha" questions targets what they see as [...]

Self-Authentication: Why Scripture Doesn’t Need External Validation

"How can the Bible prove itself? Isn't that circular reasoning?" This objection echoes through university classrooms, coffee shop discussions, and [...]

The Racial Diversity Question: Does the Bible Have Answers?

Walk into any bustling metropolis today and you'll likely witness humanity's breathtaking diversity—the deep ebony skin of a Sudanese family, [...]

Do Christians Need Holy Shrines? Why the Reformed Answer Is No

Walk into a medieval cathedral and you'll encounter ornate shrines, gilded reliquaries, and designated "holy places" where pilgrims gather to [...]

If God Is Sovereign, Why Bother Praying?

DOESN’T DIVINE SOVEREIGNTY OBVIATE PRAYER? **Editor’s Note: This post is part of our series, ‘Satan’s Lies: Common Deceptions in the [...]

I Want To Believe, But Can’t: What Do I Do?

"I want to believe in God. I really do. But I just can't seem to make it happen. I've tried [...]

BC 1446 or 1250: When Did the Exodus Really Happen?

WHY REFORMED SCHOLARS SUPPORT THE EARLY DATE Many a critic makes the claim: “Archaeology has disproven the biblical account [...]

Does God Know the Future? All of It, Perfectly?

Think about this: our prayers tell on us. Every time we ask God for something, we’re confessing—often without realising it—what [...]

Can Christian Couples Choose Permanent Birth Control?

Consider Sarah, whose fourth pregnancy nearly killed her due to severe pre-eclampsia, leaving her hospitalised for months. Or David and [...]