The Calvinist View of Human Free Will: Are We Truly Free?

Imagine falling into a deep, dark well with walls too steep to climb. Every attempt to escape is futile, leaving you exhausted and sinking further into despair. Just when all hope seems lost, someone appears above and throws down a rope, pulling you to safety. Now, imagine boasting afterward that you were clever enough to grab the rope. While you did grip it, could you truly have escaped without the one who pulled you up? Of course not; your rescue wasn’t about your strength or wisdom but about the power of the one who saved you.

The Calvinist view of human free will is much like this. We’re all in a spiritual pit from which we cannot escape on our own, bound by sin and powerless to reach God by our own strength. While we might choose to cling to Him once we’re reached, it is God who first lowers the rope, grips us, and lifts us out of the darkness. In this view, human free will is real but limited, entirely reliant on God’s sovereign grace to act. It is He who takes the initiative to save us, and without His work, we’d remain trapped, with no way to climb out on our own.

The Foundation: Total Depravity

At the heart of Calvinist thought lies the doctrine of total depravity. This teaching asserts that human nature was fundamentally corrupted through Adam’s fall, affecting every aspect of human existence—including our will. According to this view, we aren’t just damaged or hindered by sin; we’re spiritually dead, unable to choose God or pursue genuine righteousness without divine intervention.

This doesn’t mean we’re as evil as we can be, or that we’re incapable of doing things that appear good. Rather, it means even our best actions are tainted by selfish motives and fall short of God’s perfect standard. As Calvin himself wrote, the human will is “not only weak and useless but completely dead to righteousness.”

Predestination and Divine Sovereignty

Building on this foundation, Calvinism emphasises God’s absolute sovereignty over all events, including human salvation. The doctrine of unconditional election teaches that God, before the foundation of the world, chose those who would be saved—not based on foreseen faith or good works, but according to His own purpose and pleasure.

This extends to what’s known as double predestination: God actively ordains not only who will be saved but also who will not be. While this might seem harsh to modern sensibilities, Calvinists argue it’s the logical conclusion of divine sovereignty and finds support in passages like Romans 9, where Paul discusses God’s choice of Jacob over Esau before either had done good or evil.

Understanding Compatibilism—Calvinist Free Will

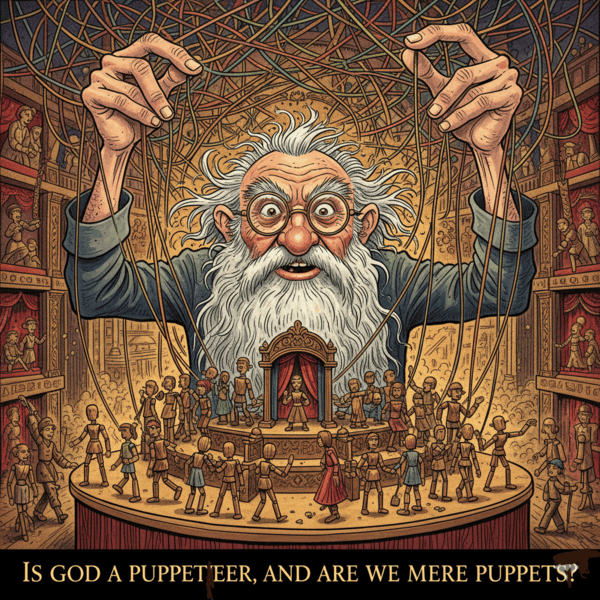

Contrary to common misconceptions, Calvinism doesn’t deny human free will entirely. Instead, it redefines it. In Calvinist thought, we always act according to our strongest desires and make real, voluntary choices. However, because of our fallen nature, our desires are fundamentally oriented away from God unless He intervenes to change them.

This view, often called COMPATIBILISM is the idea that determinism and moral responsibility are compatible. We make genuine choices based on our wants and preferences, but these choices are themselves determined by factors outside our control, ultimately traceable to God’s sovereign will.

Common Misconceptions

It’s crucial we don’t confuse Calvinism with fatalism. Fatalism suggests our choices don’t matter because everything is predetermined. Calvinism, by contrast, maintains our choices are real and significant—they’re simply guaranteed by God’s decree rather than independent of it.

Moreover, Calvinists don’t believe God forces us against our will to believe or disbelieve. Rather, God changes the hearts of the elect so they can freely choose Him. As Jonathan Edwards argued, the will always chooses according to its strongest inclination—and regeneration simply changes what we most desire.

Practical Implications

This theological framework has profound practical implications. Far from encouraging passivity, Calvinism has historically motivated vigorous evangelical and missionary efforts. After all, if God has chosen people for salvation, He will surely use means—including human agency—to bring them to faith.

The doctrine also provides comfort in prayer and spiritual disciplines. Believers can trust that God is sovereign over their spiritual growth, while still taking seriously their responsibility to pursue holiness. This paradox of divine sovereignty and human responsibility becomes a source of both humility and confidence.

Contemporary Debates

Modern discussions of Calvinist free will often centre on its contrast with Arminianism, which emphasises human free will in salvation. Contemporary debates also engage with questions raised by scientific determinism and modern philosophy of mind.

Some modern Reformed thinkers have sought to soften traditional Calvinist determinism, while others maintain its historical rigour. These discussions demonstrate the continuing relevance of these questions to both theological and philosophical inquiry.

Conclusion

Calvinism’s view of free will represents a sophisticated attempt to reconcile divine sovereignty with human responsibility. While it raises challenging questions, it also offers a coherent framework for understanding human agency in relation to divine control.

The Calvinist perspective reminds us theological precision needn’t diminish Christian devotion or mission. Indeed, contemplating these deep truths about God’s sovereignty and human will can lead to greater worship and more faithful service, even as we continue to wrestle with their implications.

Rather than seeing divine sovereignty as a barrier to human significance, Calvinism presents it as the very foundation that makes human choice meaningful. In this view, our decisions matter precisely because they’re part of God’s eternal plan, not in spite of it.

The Calvinist View of Human Free Will—Related FAQs:

What is the difference between the classical definition of free will and how it’s defined in the Reformed tradition? The classical or libertarian definition of free will posits that for a choice to be free, it must be possible for a person to choose differently under identical circumstances—often called the “power of contrary choice.” The Reformed tradition, by contrast, defines free will as the ability to act according to one’s strongest desires without external coercion, even if those desires themselves are determined by God and our nature. This compatibilist view maintains that an action can be both predetermined and freely chosen, as long as it aligns with the agent’s own wishes and intentions.

How is free will different from total autonomy? Free will in Calvinist thought refers to the ability to make voluntary choices according to our desires, while total autonomy suggests complete independence from external influences, including God. Reformed theology argues that true autonomy is neither possible nor desirable, as creatures are necessarily dependent on their Creator and influenced by their nature, circumstances, and relationships. The Calvinist view sees human freedom as operating within the context of God’s sovereignty, much like how a fish is most free when swimming within water—its natural element—rather than flopping on the shore in “autonomy” from its intended environment.

Does Calvinism make God the author of sin? Calvinism maintains that while God sovereignly ordains everything that comes to pass, He does so in a way that preserves both His holiness and human responsibility for sin. Reformed theologians argue God permits and uses evil for His purposes without directly causing or approving of it, similar to how an author writes villains into a story without personally endorsing their actions. The distinction lies in God’s different relationships to good and evil: He actively causes good but merely permits and directs evil, working through secondary causes while remaining untainted by sin Himself.

Is human responsibility still meaningful if we’re incapable of choosing God? Reformed theology argues that responsibility doesn’t require ability but rather focuses on obligation and accountability to God as our Creator. Humans remain responsible for their choices because they make them willingly according to their own desires, even though those desires are corrupted by sin and can only be changed by divine grace. This view parallels how we hold people accountable for actions they “couldn’t help” doing when the inability stems from their own character or chosen disposition.

What is the biblical basis for believing in compatibilism? Scripture consistently presents both divine sovereignty and human responsibility without viewing them as contradictory, as seen in passages like Genesis 50:20 where Joseph’s brothers’ evil actions are simultaneously their choice and God’s plan. The Bible frequently attributes actions to both divine and human agency, such as in Philippians 2:12-13 where believers are commanded to work out their salvation while acknowledging that God works in them. This biblical pattern aligns with compatibilism’s assertion that God’s sovereignty and human responsibility are not competing explanations but complementary truths operating at different levels.

The Calvinist View of Human Free Will—Our Related Posts

Editor's Pick

Why Do People Hate the Doctrine of Election?

…WHEN THEY REALLY SHOULDN’T Few Bible doctrines provoke stronger reactions than election. The idea that God chose some for salvation [...]

The Doctrine of Providence: Does God Really Govern All Things?

You’re sitting in the doctor’s office when the diagnosis lands like a thunderclap. Your mind races: Why this? Why now? [...]

No Decay, No Defeat: What It Means That Christ’s Body Saw No Corruption

On the Day of Pentecost, Peter stood before thousands and made a startling claim: David's body decayed in the tomb, [...]

SUPPORT US:

Feel the Holy Spirit's gentle nudge to partner with us?

Donate Online:

Account Name: TRUTHS TO DIE FOR FOUNDATION

Account Number: 10243565459

Bank IFSC: IDFB0043391

Bank Name: IDFC FIRST BANK