The Omni Argument: Does Calvinism Get God’s Love Wrong?

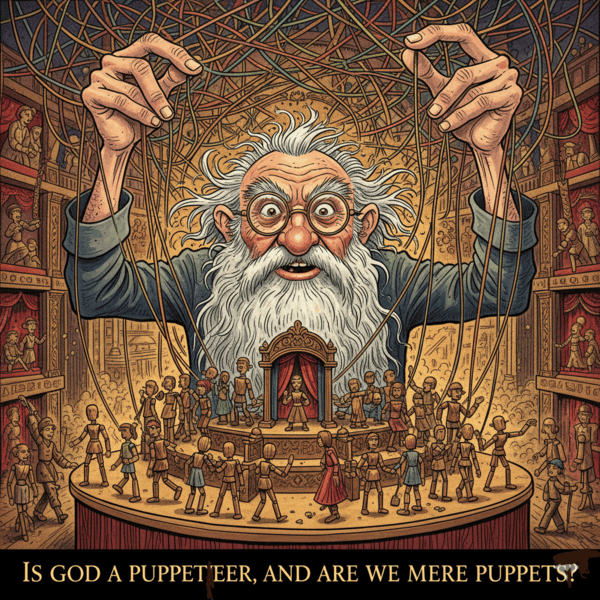

Few objections to Reformed theology cut as deeply as the Omni Argument. The name comes from God’s “omni” attributes—He is omnipotent (all-powerful) and omnibenevolent (all-loving)—which critics argue contradict Calvinism’s claims. The argument is emotionally powerful, philosophically sharp, and strikes at the heart of what we believe about God’s character. The logic seems airtight: If God is all-powerful and all-loving, and if His grace is truly irresistible, why doesn’t He save everyone? The Calvinist answer—that God chooses to save some and pass over others—sounds to many ears like a denial of either God’s power or His love.

Molinists sharpen the critique even further. They argue God possesses “middle knowledge”—knowledge of what every person would freely choose in any possible circumstance. Armed with this knowledge, God could have created a world where everyone freely accepts salvation, or at least where far more are saved. That He didn’t, they claim, reveals a troubling gap in either His love or His justice.

These are serious challenges that deserve serious answers. But Reformed theology offers responses that aren’t only biblically grounded but deeply satisfying—responses that actually magnify God’s love rather than diminish it.

UNDERSTANDING GOD’S WILL: THE KEY DISTINCTION

The Omni Argument stumbles at its starting premise: what we mean by God’s “love” and “desire.” Scripture reveals God has both a decretive will (what He sovereignly ordains) and a preceptive will (what He commands and delights in morally). These aren’t contradictory but complementary.

When 1 Timothy 2:4 says God “desires all people to be saved,” it’s expressing His preceptive will—His genuine moral disposition, His revealed heart in the gospel call. God takes no pleasure in the death of the wicked (Ezekiel 33:11) and sincerely invites all to come. Yet Ephesians 1:11 declares God “works all things according to the counsel of his will.” His sovereign plan includes both those He saves and those He passes over in judgement.

Consider Pharaoh. God genuinely commanded him to let Israel go—repeatedly, through Moses, with signs and wonders. Yet God also declared, “I will harden his heart” (Exodus 4:21). Was God being duplicitous? No. He was displaying both His righteous demand for obedience and His sovereign purpose in judgement.

God is not deceitful when both wills operate simultaneously—He is complex, like a just judge who sincerely offers pardon to a criminal while knowing he will decree the sentence the law requires. The offer is genuine, the consequences are real, and the judge’s integrity remains intact. The cross itself is the ultimate proof: God offers salvation to all who believe, and He actually secures that salvation for the elect. The non-elect still receive a sincere external call and real common grace, but not the internal, effectual call that unites them to Christ.

This is mystery, yes—but not contradiction. The Reformed position doesn’t make God’s love a sham. It recognises God’s saving love is real without being universal in its extent. He genuinely offers Christ to all; He grants common grace to all; He sincerely commands all to repent. But His electing love—the love that infallibly secures salvation—is particular, not universal.

GOD’S GLORY: MORE THAN MERE NICENESS

Here’s where the Omni Argument makes a fatal assumption: that God’s goodness is reducible to maximising human salvation. But Scripture paints a richer picture.

Romans 9:22-23 is crucial: “What if God, desiring to show his wrath and to make known his power, has endured with much patience vessels of wrath prepared for destruction, in order to make known the riches of his glory for vessels of mercy?” God’s glory is displayed through both mercy and justice, compassion and wrath.

God’s holiness demands that sin be punished. His justice requires that rebellion not go unanswered. All humanity stands justly condemned (Romans 3:23, Ephesians 2:3)—dead in trespasses, children of wrath, hostile to God. The staggering reality isn’t that God saves only some, but that He saves any at all.

Notice what Paul does NOT say in Romans 9. He never appeals to foreseen faith or to libertarian freedom. He appeals to God’s authority as Creator: ‘Shall the thing formed say to him who formed it, “Why have you made me like this?”’ (v. 20). The very objection the Omni Argument raises is the one Paul anticipates and silences—not by explaining middle knowledge or resistible grace, but by saying God has the right to make vessels for honourable use and others for common use. The Potter’s freedom is the point.

When we grasp our true condition—spiritually dead, wilfully rebellious, utterly unable to save ourselves—God’s electing grace becomes breathtakingly magnificent. He didn’t merely make salvation possible; He made it certain for His chosen ones. That’s not unloving; that’s the very essence of grace: undeserved, unsought, unstoppable mercy.

WHAT SCRIPTURE ACTUALLY TEACHES

The Reformed position isn’t philosophical speculation—it’s biblical exposition. Consider these clear texts:

- John 6:37, 44: Jesus explicitly connects coming to Him with the Father’s prior giving and drawing. Election precedes faith.

- Ephesians 1:4-5: God’s choice happened before we existed, before we believed, before we did anything good or bad. It was according to “the purpose of His will”—not ours.

- Romans 9:11-16: Jacob and Esau were chosen before birth, “before they had done anything good or bad.” Paul concludes: “It depends not on human will or exertion, but on God who has mercy.”

- Acts 13:48: “And when the Gentiles heard this, they began rejoicing and glorifying the word of the Lord, and as many as were appointed to eternal life believed.” Appointment preceded belief.

The pattern then, is unmistakable: God’s sovereign choice grounds our salvation. We don’t choose Him and then get elected; He elects us, and therefore we believe. Our wills are enslaved to sin (John 8:34) until grace liberates them.

WHY THE MOLINIST ALTERNATIVE FAILS

The Molinist proposal sounds attractive—God sovereignly chooses which world to create, while we freely choose within it. But it crumbles under scrutiny.

- Middle knowledge is philosophically incoherent. If choices are truly “free” in the libertarian sense (undetermined by prior conditions), there are no true facts about what someone would freely choose. You can’t know an undetermined choice before it’s made.

- Molinism makes God reactive rather than sovereign. He’s stuck choosing among options rather than authoring all things. This directly contradicts texts like Ephesians 1:11 and Proverbs 16:9.

- It fails to account for texts that speak of unconditional election. Romans 9 insists God’s choice is “not because of works”—yet Molinism grounds election in foreseen responses to grace.

Molinism has God electing in light of our faith; Scripture has us believing in light of His election (Acts 13:48; John 10:26–29; 2 Tim 1:9). The order is decisive.

THE BEAUTY OF SOVEREIGN GRACE

Far from diminishing God’s love, Reformed theology secures it. If salvation depended partly on our will, no one could have assurance. But Romans 8:29-30 gives us a “golden chain”: those predestined are called, justified, and glorified—with no link breaking.

This doctrine humbles human pride and exalts divine mercy. It assures troubled souls that salvation rests not on their flickering faith but on God’s unchanging purpose. And it gives all glory where it belongs: to the God who “works all things according to the counsel of his will.”

Does this involve mystery? Absolutely. But it’s the mystery of a God whose thoughts are higher than ours (Isaiah 55:8-9), whose ways are past finding out (Romans 11:33). We stand not as critics demanding God justify Himself to us, but as creatures marvelling that He would save rebels like us at all.

That’s not getting God’s love wrong. That’s getting it gloriously right. The glory of the gospel is that God saves ill-deserving sinners without becoming unjust to the rest.

RELATED FAQs

If God decrees everything, doesn’t that make Him the author of sin? Reformed theology distinguishes between God’s sovereign decree and moral responsibility. God ordains that sin occurs, but always through the willing choices of responsible agents—He never coerces evil or sins Himself. As the Westminster Confession states, God’s decree establishes “the liberty or contingency of second causes” rather than eliminating them. Think of Joseph’s brothers: they freely chose evil, yet God sovereignly ordained it for good (Genesis 50:20). God’s decree renders events certain without rendering human agents innocent.

- How do prominent Reformed thinkers today respond to the Omni Argument? John Piper emphasises that God’s purpose includes displaying both wrath and mercy for His glory, not merely maximising saved souls. RC Sproul argued the real question isn’t “Why doesn’t God save everyone?” but “Why does God save anyone at all?” James White points out Arminians face the same problem—if God foresees who will reject Him, why create them? Michael Horton stresses that election magnifies grace precisely because it’s undeserved and unconditional, making salvation a gift rather than a reward.

- If God passes over the non-elect, isn’t that the same as actively damning them? Reformed theology distinguishes between preterition (passing over) and condemnation. God’s “passing over” is permissive—He simply doesn’t extend saving grace. Condemnation, however, is always based on actual sin and guilt. No one goes to hell merely for not being elect; they go for their own willful rebellion. As Romans 1-2 makes clear, all humanity stands justly condemned apart from grace. Election is God’s merciful intervention; non-election is leaving people in their chosen state of rebellion.

How can we be responsible for faith if God has to give it to us? Responsibility doesn’t require libertarian freedom—it requires acting according to your nature and desires. The non-elect don’t want to come to Christ (John 5:40); their slavery to sin is voluntary, not coerced. When God regenerates the elect, He doesn’t override their will—He transforms it, making them willing. As Augustine said, grace doesn’t force the unwilling but makes the unwilling willing. We’re responsible for our choices even though those choices flow from our nature, whether sinful or regenerate.

- What about 2 Peter 3:9, which says God is “not willing that any should perish”? Reformed interpreters note the context: Peter is writing to believers (“the beloved”) and says God is patient toward “you” (the elect), not willing that any of you should perish. The “any” refers to the elect scattered among the nations, not every human being without exception. This aligns with John 6:39 where Jesus says, “I should lose nothing of all that he has given me.” God’s salvific will is particular and effectual, ensuring that none of His chosen ones perish.

- Doesn’t this doctrine make evangelism pointless if God has already decided who will be saved? Quite the opposite—it makes evangelism confident and hopeful! We know God has elect people “in every nation” (Revelation 5:9) and our preaching is His appointed means to call them. Paul evangelised Corinth because God told him, “I have many in this city who are my people” (Acts 18:10). Election guarantees evangelism will succeed, not fail. We preach not knowing who the elect are but knowing they’re out there and will certainly respond when they hear the gospel.

How do Reformed believers avoid becoming fatalistic or cold-hearted toward the lost? True Reformed believers mirror Paul’s heart in Romans 9:1-3—profound sorrow for the lost combined with confidence in God’s justice. Knowing God sovereignly saves doesn’t diminish compassion; it intensifies gratitude and humility. We recognise we’re no better than anyone perishing—“but for the grace of God, there go I.” Historic Reformed communities (Puritans, Dutch Reformed, Presbyterians) have been marked by passionate evangelism, missions, and social concern precisely because they believed God’s sovereign grace would make their efforts fruitful.

OUR RELATED POSTS

- Is Calvinism Unbiblical? Revisiting Wesley’s Classic Objections

- Is Calvinism Fatalism in Christian Disguise? Think Again

- The Calvinist View of Human Free Will: Are We Truly Free?

- 4-Point Calvinism: Can I Be a Calvinist and Deny Limited Atonement?

- Calvinism vs Molinism: A Deep Dive into the Debate

- The Calvinist-Arminian Debate

Editor's Pick

Why Do People Hate the Doctrine of Election?

…WHEN THEY REALLY SHOULDN’T Few Bible doctrines provoke stronger reactions than election. The idea that God chose some for salvation [...]

The Doctrine of Providence: Does God Really Govern All Things?

You’re sitting in the doctor’s office when the diagnosis lands like a thunderclap. Your mind races: Why this? Why now? [...]

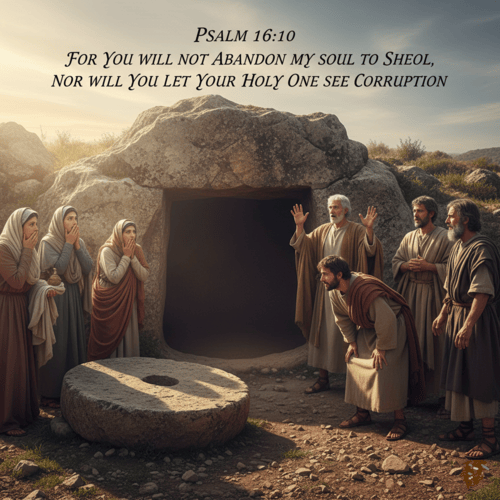

No Decay, No Defeat: What It Means That Christ’s Body Saw No Corruption

On the Day of Pentecost, Peter stood before thousands and made a startling claim: David's body decayed in the tomb, [...]

SUPPORT US:

Feel the Holy Spirit's gentle nudge to partner with us?

Donate Online:

Account Name: TRUTHS TO DIE FOR FOUNDATION

Account Number: 10243565459

Bank IFSC: IDFB0043391

Bank Name: IDFC FIRST BANK