The Rahab Mystery: Why Is A Prostitute in Jesus’ Family Tree?

When we read through Jesus’ genealogy in Matthew’s Gospel, most names pass by in expected succession—Abraham, Isaac, Jacob, all the way to “Joseph, the husband of Mary, of whom was born Jesus, who is called Christ.” But several names catch our attention precisely because they seem out of place. Among these unexpected inclusions stands Rahab, a Canaanite prostitute whose dramatic story is told in the book of Joshua.

Her presence raises immediate questions: What’s she doing in the lineage of the Messiah? How could someone with her background become an ancestor of the Holy One of Israel? The truth is, if God were to look for only worthy people to include in His Son’s lineage, He wouldn’t have found any. Rahab’s story reveals profound truths about God’s character and the nature of his redemptive plan—a plan that has always worked through unworthy vessels to showcase His extraordinary grace.

THE UNLIKELY CANDIDATE: WHY RAHAB “SHOULDN’T” BE THERE

By conventional standards of ancient Jewish genealogy, Rahab faced two insurmountable barriers that should have excluded her from this prestigious lineage:

- The Gender Barrier: In the patriarchal culture of ancient Israel, genealogies primarily traced male descent. Women were rarely mentioned except in unusual circumstances. Yet Matthew intentionally includes five women in Jesus’ genealogy—Tamar, Rahab, Ruth, Bathsheba (the wife of Uriah), and Mary—signaling something profoundly significant about God’s redemptive purposes.

- The Ethnic Barrier: More strikingly, Rahab was a Canaanite, belonging to a people explicitly marked for judgement. The Canaanites were idolaters whose practices were so abhorrent that God commanded Israel to drive them out completely (Deuteronomy 7:1-2). They represented everything opposed to God’s covenant people. By all normal expectations, a Canaanite should be the last person to appear in the Messiah’s family line.

Add to these her occupation as a prostitute, and Rahab represents a trifecta of “disqualifications.” Yet here she stands, honoured in Scripture as an ancestor of Jesus Christ and even celebrated in Hebrews 11’s “Hall of Faith.”

THE REFORMED PERSPECTIVE ON RAHAB’S INCLUSION

Reformed theology provides particularly rich insights into why Rahab’s inclusion is not merely incidental but profoundly meaningful to the gospel narrative.

Divine Sovereignty in Election: At the heart of Reformed thought is the conviction salvation originates entirely in God’s sovereign choice, not human merit or status. Rahab’s presence in the genealogy powerfully illustrates this truth. God chose her—a Gentile prostitute living in a condemned city—to play a crucial role in redemptive history.

This exemplifies “unconditional election.” God did not choose Rahab because she was morally superior or strategically valuable, but solely according to His gracious purpose.

Faith as the Marker of Covenant Inclusion: What distinguished Rahab was not her background but her faith. In Joshua 2:11, she makes a remarkable confession: “The LORD your God is God in heaven above and on the earth below.” This declaration reveals genuine belief that led to decisive action.

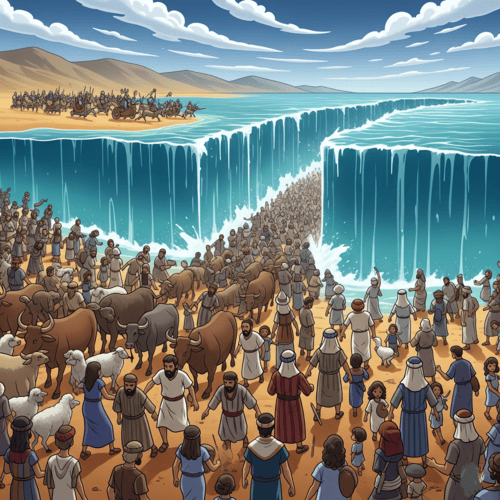

Reformed theology emphasises that covenant membership has always been fundamentally about faith, not ethnicity. As Paul would later argue in Romans 4, Abraham himself—the father of the Jewish nation—was justified by faith, not works or heritage. Rahab, though a Gentile, demonstrated the same faith that characterised God’s true people throughout history. Her incorporation into Israel (Joshua 6:25) foreshadows how Gentiles would be “grafted in” to God’s people through faith.

Total Depravity and Radical Grace: Perhaps no aspect of Rahab’s story better illustrates Reformed theology than the contrast between human sinfulness and divine grace. Reformed thought emphasises humanity’s total depravity—not that everyone is as depraved as possible, but that sin affects every aspect of our being.

Rahab’s former life represents the depth of human fallenness. Yet her transformation demonstrates God’s grace penetrates even the most unlikely places. She moved from being an idolatrous prostitute to an ancestor of Christ—a change no human could orchestrate.

THE SCARLET CORD AS A TYPE OF CHRIST

One of the most striking elements of Rahab’s story is the scarlet cord she hung from her window—a sign protecting her household from destruction. Reformed biblical interpretation has long recognised this as a rich type of Christ’s saving work.

Blood Protection: When the Israelites attacked Jericho, Rahab’s household was spared because of the scarlet cord marking her home—a vivid parallel to the Passover blood that protected the Israelites in Egypt. This foreshadows salvation through Christ’s blood, a central doctrine in Reformed soteriology.

The cord’s scarlet colour itself points to blood, emphasising protection from judgement requires blood atonement. As Calvin noted, all Old Testament signs of salvation ultimately point to Christ, in whom they find their fulfillment.

Visible Sign of Inward Faith: Reformed theology emphasises the relationship between inward faith and outward signs. The scarlet cord represented Rahab’s trust in the Israelites’ promise—a visible manifestation of her faith. Yet the cord itself had no magical properties; it was meaningful only because of the covenant promise it represented.

This parallels the Reformed understanding of sacraments as signs and seals of God’s promises, effective not by themselves but through faith in what they signify. Rahab’s action in hanging the cord demonstrated active trust in God’s provision for salvation.

Covenant Marker: The cord created a clear distinction between those under protection and those facing judgement. This binary division—between those inside and outside Rahab’s house—aligns with the Reformed emphasis on God’s covenant faithfulness to His people.

Everyone inside the protection of the scarlet cord was saved, regardless of their personal history, just as all who are in Christ are saved regardless of their past. The cord thus foreshadows how Christ’s blood creates a clear boundary between those who’re perishing and those who’re being saved.

THEOLOGICAL IMPLICATIONS FOR THE CHURCH TODAY

Rahab’s story continues to speak powerfully to contemporary Christians, particularly from a Reformed perspective.

Radical Inclusion Through Sovereign Grace: If God incorporated a Canaanite prostitute into the Messiah’s lineage, clearly His grace knows no boundaries of gender, ethnicity, or moral history. This challenges churches to embrace all whom God calls, recognising divine election transcends human categories and prejudices. Rahab reminds us the ground at the foot of the cross is perfectly level.

Faith Over Heritage: Rahab demonstrates true covenant membership depends on faith, not biological descent. This Reformed emphasis on the “invisible church” defined by election rather than external markers remains profoundly relevant in an age of cultural Christianity. God’s family includes many who lack religious pedigree but possess genuine faith. Conversely, those with impeccable religious credentials but without true faith remain outside the covenant.

From Prostitute to Princess: Perhaps most encouraging is Rahab’s complete transformation. Jewish tradition holds she married Salmon and became the mother of Boaz, making her the great-great-grandmother of King David. From prostitute to princess in David’s royal line—and ultimately in Christ’s lineage. God doesn’t merely forgive sin; He grants new identity and purpose. In Christ, believers don’t simply receive pardon; they become “new creation” (2 Corinthians 5:17), with their past no longer defining their future.

CONCLUSION: THE RAHAB MYSTERY

Rahab stands in Jesus’ genealogy not despite her gender, ethnicity, and occupation, but precisely because these “disqualifications” highlight the sovereign grace at the heart of God’s redemptive work. Her presence announces the Messiah came not for the self-righteous but for sinners; not merely for one nation but for all peoples.

Rahab’s story beautifully illustrates the core Reformed doctrines of unconditional election, justification by faith alone, and the transformative power of divine grace. In Rahab, we see a God who delights in demonstrating His grace by choosing the unlikely, transforming the unworthy, and including the outsider in His redemptive purposes. Her presence in Jesus’ family tree isn’t an embarrassment to be explained away but a testimony to be celebrated—a powerful reminder the gospel is indeed “the power of God for salvation to everyone who believes” (Romans 1:16). We don’t deserve to be among God’s redeemed community any more than Rahab does. And yet, like her, here we are too. Glory be to God alone.

THE RAHAB MYSTERY: RELATED FAQs

Who were the other women mentioned in Jesus’ genealogy, and why are they significant? Matthew includes four other women besides Rahab: Tamar, Ruth, Bathsheba (“wife of Uriah”), and Mary. Each woman’s story involves unusual circumstances that highlight God’s sovereign work through seeming irregularities—Tamar through deception, Ruth as a Moabite foreigner, Bathsheba through David’s sin, and Mary through virgin conception. Their inclusion demonstrates God’s pattern of working through situations that human wisdom would consider scandalous or problematic, showcasing His redemptive purposes that transcend human expectations and moral failings.

- Was Rahab actually a prostitute, or could this be a mistranslation? The Hebrew word “zonah” used to describe Rahab consistently means “prostitute” throughout the Old Testament, and the New Testament authors explicitly use the Greek word for prostitute (James 2:25, Hebrews 11:31). While some Jewish traditions attempted to reinterpret her as an innkeeper to minimise scandal, Reformed scholarship emphasises accepting the biblical text as it stands. The power of Rahab’s story actually increases when we recognise her background—it magnifies God’s grace rather than diminishing it, showing divine election operates independently of human merit or social standing.

- How do we know Rahab in Joshua is the same Rahab mentioned in Jesus’ genealogy? Matthew 1:5 identifies Rahab as the mother of Boaz (by Salmon), creating a direct link to the Rahab from Joshua’s time. Some scholars note chronological challenges with this identification given the generations between Joshua and David, but Reformed scholars generally accept Matthew’s inspired authority on this connection. Timothy Keller notes Matthew, under divine inspiration, deliberately highlights this connection to emphasise God’s redemptive plan has always included outsiders who come to faith—making Rahab a crucial example of grace extending beyond Israel’s boundaries.

What does Rahab’s profession tell us about God’s view of sexual sin? Rahab’s inclusion in Christ’s lineage doesn’t minimise the seriousness of sexual sin but rather magnifies the scope of God’s forgiveness and transforming grace. Reformed theology emphasises that no sin—including sexual sin—places one beyond God’s redemptive reach when genuine repentance occurs. As Michael Horton writes, “God doesn’t call the qualified; He qualifies the called,” reminding us Rahab’s former identity as a prostitute was completely transformed by covenant inclusion, with her former profession becoming irrelevant to her new identity in God’s redemptive plan.

- Were there other morally complex characters in Jesus’ genealogy besides the women? Jesus’ genealogy includes numerous flawed men, including Jacob the deceiver, Judah who slept with his daughter-in-law, David the adulterer and murderer, Solomon with his idolatry, and Manasseh who sacrificed his own children. RC Sproul observed the genealogy reads like “a rogues’ gallery of sinners,” deliberately showing Christ came from and for sinners. This demonstrates the Reformed emphasis on total depravity—that no one is worthy of inclusion in God’s family—while simultaneously showcasing God’s commitment to work through broken people to accomplish His perfect purposes.

- How does Rahab’s story relate to the doctrine of effectual calling? Rahab’s conversion beautifully illustrates the Reformed doctrine of effectual calling—that God sovereignly draws His elect to faith. John Piper notes that while all Jericho heard about Israel’s God, only Rahab responded with genuine faith, showing knowledge alone doesn’t save. Her confession that “the LORD your God is God in heaven above and on earth below” (Joshua 2:11) demonstrates that God had opened her heart to recognise His sovereignty, much like Lydia in Acts 16:14. This effectual call completely transformed her allegiance from Jericho to Israel’s God, exemplifying how divine calling inevitably produces both faith and corresponding action.

What significance might Rahab have for contemporary issues of immigration and ethnic inclusion? Rahab’s incorporation into Israel provides a powerful Reformed perspective on contemporary issues of ethnic inclusion and immigration. Kevin DeYoung argues that her story shows how covenant community has always been defined by faith rather than ethnicity, with foreigners being fully incorporated when they trust in Israel’s God. Reformed theology distinguishes between civil and ecclesiastical concerns, but maintains that the church should reflect God’s heart for including people from all backgrounds who profess faith in Christ. Rahab reminds us that in God’s economy, there are no second-class citizens among those who genuinely trust Him, regardless of their origins.

THE RAHAB MYSTERY: OUR RELATED POSTS

Editor's Pick

Did Jesus Cleanse the Temple Twice?

OR DID JOHN DISAGREE WITH THE SYNOPTICS ON TIMING? One of sceptics’ favourite "gotcha" questions targets what they see as [...]

Self-Authentication: Why Scripture Doesn’t Need External Validation

"How can the Bible prove itself? Isn't that circular reasoning?" This objection echoes through university classrooms, coffee shop discussions, and [...]

Do Christians Need Holy Shrines? Why the Reformed Answer Is No

Walk into a medieval cathedral and you'll encounter ornate shrines, gilded reliquaries, and designated "holy places" where pilgrims gather to [...]

I Want To Believe, But Can’t: What Do I Do?

"I want to believe in God. I really do. But I just can't seem to make it happen. I've tried [...]

BC 1446 or 1250: When Did the Exodus Really Happen?

WHY REFORMED SCHOLARS SUPPORT THE EARLY DATE Many a critic makes the claim: “Archaeology has disproven the biblical account [...]

Does God Know the Future? All of It, Perfectly?

Think about this: our prayers tell on us. Every time we ask God for something, we’re confessing—often without realising it—what [...]

Can Christian Couples Choose Permanent Birth Control?

Consider Sarah, whose fourth pregnancy nearly killed her due to severe pre-eclampsia, leaving her hospitalised for months. Or David and [...]

Bone of My Bones: Why Eve Was Created From Adam’s Body

"This at last is bone of my bones and flesh of my flesh!" Adam's joyful exclamation upon first seeing Eve [...]

Is Calvinism Fatalism in Christian Disguise? Think Again

We hear the taunt every now and then: "Calvinism is just fatalism dressed up in Christian jargon." Critics argue Reformed [...]

Can Churches Conduct Same-Sex Weddings?

In an era of rapid cultural change, churches across America face mounting pressure to redefine their understanding of marriage. As [...]

SUPPORT US:

Feel the Holy Spirit's gentle nudge to partner with us?

Donate Online:

Account Name: TRUTHS TO DIE FOR FOUNDATION

Account Number: 10243565459

Bank IFSC: IDFB0043391

Bank Name: IDFC FIRST BANK