Can We Trust John’s Gospel? Answering Your Toughest Challenges

John’s Gospel is distinct among the four biblical accounts of Jesus’ life. With its profound theological language, extended discourses, and unique stories, it has become both a cornerstone of Christian faith and a target for sceptic criticism. Modern critics question its historical reliability, suggesting it was written too late, by someone other than John, or with too much theological agenda to be trusted. But are these criticisms warranted? Let’s examine the evidence that suggests John’s Gospel is indeed reliable and deserving of its place in the biblical canon.

ADDRESSING THE DATING QUESTION

Modern scholarship provides compelling evidence for an early dating of John’s Gospel, contrary to sceptic claims of late second-century composition:

Archaeological discoveries have repeatedly confirmed John’s detailed knowledge of pre-70 AD Jerusalem. The Pool of Bethesda with its five porticoes (John 5:2) was once dismissed as fictional until excavations uncovered precisely such a structure. Similarly, the Pool of Siloam (John 9:7) has been unearthed exactly where John described it.

Papyrus evidence also supports early dating. The John Rylands papyrus (P52), containing fragments of John 18, dates to approximately 125-130 AD. This means the gospel was already circulating throughout the Mediterranean within a single generation after the events it describes—hardly enough time for legends to develop.

The text itself shows no awareness of Jerusalem’s destruction in 70 AD, a cataclysmic event that would surely have been mentioned had the gospel been written after it occurred. Instead, John describes Jerusalem’s landmarks in the present tense, suggesting they still stood when he wrote.

THE EYEWITNESS PERSPECTIVE IN JOHN’S GOSPEL

John’s Gospel repeatedly claims to be rooted in eyewitness testimony:

“This is the disciple who testifies to these things and who wrote them down. We know that his testimony is true” (John 21:24).

The text contains numerous vivid details that only an eyewitness would include: the weight of perfume Mary used to anoint Jesus (12:3), the number of water jars at Cana (2:6), and even the number of fish caught in the resurrection appearance (153 large fish, 21:11). These “unnecessary details” bear the unmistakable mark of eyewitness recollection rather than later invention.

The author demonstrates intimate knowledge of Jewish customs, religious debates, and geographical locations that would be difficult for a non-Palestinian, non-Jewish author of a later generation to fabricate. For example, his accurate description of controversies regarding Sabbath observance and his thorough understanding of Passover traditions reflect authentic first-century Jewish context.

THEOLOGICAL CONSISTENCY WITH OTHER GOSPELS

Despite its distinctive style and emphasis, John’s theology remains fundamentally consistent with the Synoptic Gospels:

While John presents Jesus making more explicit claims to divinity, these claims are consistent with the implicit Christology of Matthew, Mark, and Luke. Jesus’ authority over sin, nature, and death found in the Synoptics aligns perfectly with John’s more direct divine claims.

The apparent chronological differences (such as the timing of the cleansing of the temple or the Last Supper) may be understood as complementary rather than contradictory accounts, each emphasising different theological aspects of the same historical events.

John’s emphasis on Jesus as the fulfilment of Old Testament themes and prophecies parallels similar connections made throughout the Synoptics. Both present Jesus as the culmination of God’s redemptive work through Israel’s history.

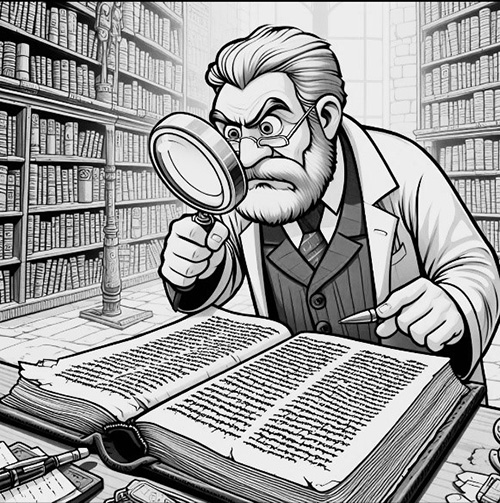

HISTORICAL RELIABILITY ARGUMENTS

John demonstrates remarkable historical accuracy that would be unlikely in a late, non-eyewitness account:

The gospel correctly portrays complex Roman-Jewish political relationships, including the limited authority of Jewish leaders under Roman rule. John’s depiction of Pilate’s reluctant involvement in Jesus’ trial aligns perfectly with what we know of the governor from other historical sources.

Recent archaeological findings have confirmed previously questioned details, such as stone water jars for purification (2:6), the existence of Jacob’s well (4:6), and the Roman stone pavement (Gabbatha) where Jesus was tried (19:13).

The author demonstrates familiarity with pre-70 AD Jerusalem that would be nearly impossible for a later writer to recreate. His knowledge of locations, distances, and local customs reflects someone intimately familiar with the land and its people.

EARLY CHURCH RECOGNITION AND USAGE

The early church recognised and used John’s Gospel extensively:

Irenaeus (c. 180 AD) explicitly attributes the gospel to “John, the disciple of the Lord who leaned on His breast,” providing a clear link to apostolic authorship. As a disciple of Polycarp, who knew John personally, Irenaeus represents a direct chain of testimony.

Even earlier, Justin Martyr (c. 150 AD) quotes from John’s Gospel, demonstrating its circulation and acceptance within a generation of its composition.

The gospel appears in our earliest canonical lists and was universally accepted by orthodox Christians, despite their typically cautious approach to accepting texts as scripture.

Importantly, even critics who questioned aspects of John acknowledged its antiquity. No credible ancient sources suggest it was a late second-century creation.

THEOLOGICAL SIGNIFICANCE AND PURPOSE

John himself explains his purpose: “These are written that you may believe that Jesus is the Christ, the Son of God, and that by believing you may have life in his name” (20:31).

This theological focus doesn’t undermine historical reliability—it explains it. John selected those events and teachings that most clearly demonstrated Jesus’ identity and mission, organising them to highlight their significance—rather than strictly chronologically.

John’s Gospel provides theological depth that complements the Synoptics. Jesus’ “I Am” proclamations, for instance, or His extended discourses explore dimensions of His teaching that’s only hinted at elsewhere. The nature of being born again, the bread of life, the good shepherd—all of these complement and enrich the Synoptics, rather than contradicting them.

Throughout church history, John’s Gospel has proven indispensable for understanding the full meaning of Christ’s incarnation, death, and resurrection. It provides unique theological perspectives that have shaped Christian doctrine regarding Christ’s divine nature.

CONCLUSION: SO CAN WE TRUST JOHN’S GOSPEL?

The evidence strongly supports John’s Gospel as both historically reliable and theologically invaluable. Its eyewitness quality, historical accuracy, early dating, and theological consistency with other biblical texts all argue for its rightful place in the canon.

The scepticism directed at John often says more about modern assumptions than about the text itself. Critics frequently approach ancient texts with anachronistic expectations or philosophical biases against supernatural claims.

Rather than approaching John with suspicion, we would do well to engage it as what it claims to be—the testimony of one who walked with Jesus, witnessed His ministry, death and resurrection, and wrote “that you may believe that Jesus is the Christ, the Son of God, and that by believing you may have life in his name.”

CAN WE TRUST JOHN’S GOSPEL? THE TOUGHEST OBJECTIONS

Wasn’t John’s Gospel written too late to be reliable? While some critics date John to the late 2nd century, archaeological and manuscript evidence overwhelmingly supports a 1st-century composition, likely between 80-95 AD. The discovery of the John Rylands papyrus (P52), dated around 125-130 AD, proves the gospel was already circulating widely by then. Additionally, John’s detailed knowledge of pre-70 AD Jerusalem geography and Jewish customs strongly suggests an eyewitness account from someone intimately familiar with that time and place.

- Doesn’t John contradict the Synoptic Gospels too much to be trusted? The differences between John and the Synoptics reflect complementary perspectives rather than contradictions. John intentionally supplements the other gospels, focusing on events and teachings they omitted. While John’s presentation style differs—featuring longer discourses and more explicit theological claims—the core portrait of Jesus remains consistent across all four gospels. The apparent chronological differences often result from different organisational principles, with John arranging events theologically rather than strictly chronologically.

- Isn’t John’s theology too developed to represent Jesus’ actual teachings? The advanced theological language in John accurately reflects Jesus’ teaching, not later church developments. The Dead Sea Scrolls have revealed many of John’s supposedly “late” theological concepts were already present in pre-Christian Jewish thought. Jesus likely adjusted His teaching style for different audiences—speaking more explicitly about His divine identity in Jerusalem debates (which John emphasises) than in Galilean public teaching (featured more in the Synoptics). John’s theology is sophisticated but consistent with the implicit claims made throughout the Synoptic Gospels.

How can we trust a gospel that wasn’t written by the apostle John himself? Strong historical evidence supports apostolic authorship of John’s Gospel. Early church fathers, including Irenaeus (who learned from Polycarp, John’s direct disciple) explicitly attributed the gospel to the apostle John. The text itself claims eyewitness origins and contains numerous vivid, specific details that reflect firsthand observation. Even if John used scribes or editors (a common ancient practice), the gospel’s core content derives from apostolic testimony, explaining its early and widespread acceptance in the church.

- Doesn’t John’s portrayal of Jesus as divine reflect later church doctrine rather than historical reality? John’s high Christology is consistent with the earliest Christian beliefs, not a later development. Paul’s letters, written before any gospel, already affirm Jesus’ divine status, indicating this was standard Christian teaching from the beginning. The Synoptic Gospels, while more subtle, contain numerous passages where Jesus exercises divine prerogatives (forgiving sins, judging the world, receiving worship). John makes explicit what is implicit elsewhere, focusing on clarifying Jesus’ identity for later generations facing various heresies.

- Isn’t John’s Gospel more concerned with theology than historical accuracy? John’s theological focus doesn’t compromise his historical reliability—it explains his selective approach to events. John himself states his purpose is that readers “may believe” (20:31). So he emphasises events that most clearly reveal Jesus’ identity. Archaeological discoveries have repeatedly confirmed John’s historical accuracy regarding places like the Pool of Bethesda and Siloam. His knowledge of Jewish customs, Roman legal procedures, and Jerusalem’s geography all demonstrate that John built his theological message on a foundation of historical fact.

Why does John include so many stories and sayings of Jesus not found in other gospels? John’s unique material reflects his complementary purpose and his access to memories not recorded by the other gospel writers. As the last gospel written, John deliberately supplemented rather than duplicated the Synoptics, which were already circulating in Christian communities. His position as part of Jesus’ innermost circle (with Peter and James) gave him access to private conversations and encounters not witnessed by all disciples. Additionally, John’s longer lifespan allowed him to reflect more deeply on the significance of Jesus’ words and actions, preserving crucial teachings that might otherwise have been lost.

CAN WE TRUST JOHN’S GOSPEL? OUR RELATED POSTS

Editor's Pick

The Throne-Room Vision: Who Did Isaiah See?

The scene is unforgettable: Isaiah stands in the temple, and suddenly the veil between heaven and earth tears open. He [...]

The Angel of the Lord: Can We Be Certain It Was Christ All Along?

Throughout the Old Testament, a mysterious figure appears: the Angel of the LORD. He speaks as God, bears God’s name, [...]

SUPPORT US:

Feel the Holy Spirit's gentle nudge to partner with us?

Donate Online:

Account Name: TRUTHS TO DIE FOR FOUNDATION

Account Number: 10243565459

Bank IFSC: IDFB0043391

Bank Name: IDFC FIRST BANK