Is Occam’s Razor a Compelling Argument Against Theism?

WHY THE ARGUMENT ACTUALLY POINTS TO GOD

Picture this: You’re in a coffee shop debate with a confident sceptic who leans back in her chair and delivers what she believes is the knockout punch: “Look, Occam’s Razor shows us that simpler explanations are better. Natural processes explain everything we see without needing to invoke God. Adding God to the equation just multiplies entities unnecessarily. Case closed.”

It’s a common argument, wielded with the authority of medieval logic and modern scientific thinking. But here’s the twist: this argument fundamentally misunderstands both Occam’s Razor and the nature of explanation itself. In fact, when properly applied, the razor actually points more toward God rather than away from Him.

WHAT IS OCCAM’S RAZOR, AND WHY CALL IT A “RAZOR”?

Occam’s Razor states that “entities should not be multiplied beyond necessity”—in simpler terms, when choosing between competing explanations, prefer the one that makes the fewest unnecessary assumptions. But why a “razor”? The metaphor is perfect: just as a razor cuts away unwanted hair, this logical principle cuts away unnecessary explanatory clutter, leaving only what’s essential.

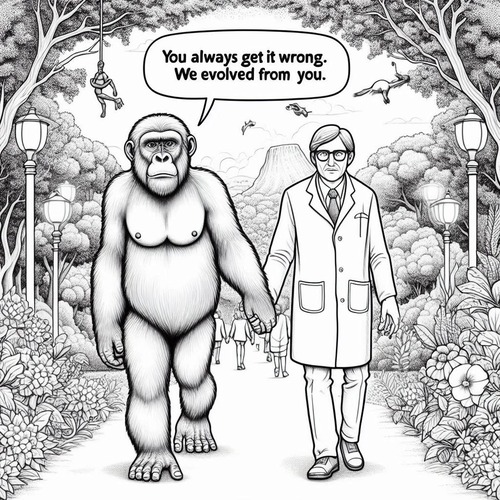

The principle gets its name from William of Ockham (1287-1347), a Franciscan friar and medieval philosopher. Here’s where the irony becomes delicious: Ockham was a devout Christian theologian who used his famous principle not to eliminate God, but as a tool for rigorous theological and philosophical reasoning. The very intellectual instrument now brandished against theism was forged in a monastery by a monk who saw it as serving, not opposing, Christian truth.

WHERE THE ATHEIST APPLICATION GOES WRONG

The standard atheist argument sounds reasonable on the surface: “Naturalistic explanations require fewer assumptions than supernatural ones. Evolution explains biological complexity, cosmology explains the universe’s origin, and physics explains natural phenomena—all without divine intervention. God is simply an unnecessary addition.”

But this commits several fundamental errors.

- It confuses ontological simplicity with explanatory power. The goal isn’t to have the fewest possible entities, but to eliminate truly redundant ones. Einstein’s theory of relativity was more complex than Newton’s mechanics, but it explained more phenomena and was therefore scientifically superior.

- It misunderstands what makes an entity “unnecessary.” Occam’s Razor eliminates redundant explanations, not foundational ones. There’s a crucial difference between invoking God as a “gap-filler” for current scientific ignorance and recognising God as the necessary ground of being itself.

- It ignores explanatory scope. Natural laws brilliantly explain how processes work, but they don’t explain why such laws exist in the first place, why they take the precise forms they do, or why anything exists at all.

THE CHRISTIAN COUNTER: THEISM IS THE SIMPLER ULTIMATE EXPLANATION

Here’s where the tables turn. When we step back and look at the total explanatory picture, theism may actually represent the more elegant solution. Consider what needs explaining: the existence of anything at all, the fine-tuning of physical constants that allow for life, the emergence of consciousness from matter, the existence of objective moral values, and the reliability of human reason itself.

Naturalism handles each of these by essentially saying “it just is.” The physical constants just happen to be life-permitting. Consciousness just emerges from complex matter. Moral intuitions are just evolutionary accidents. Reason just happens to track truth. That’s not one simple explanation—that’s multiple unexplained brute facts.

Theism, by contrast, offers a unified account: one eternal, necessary being who serves as the foundation for physical laws, the source of consciousness (being conscious Himself), the ground of moral values (reflecting His nature), and the reason our minds can comprehend reality (being made in His image). Rather than multiplying unexplained phenomena, theism traces them back to a single source.

Think of it this way: if you found a sophisticated watch, you could explain each component separately—”this gear just happens to mesh with that one, this spring just happens to provide the right tension”—or you could recognise the simpler truth that one intelligent designer created the whole system. The latter explanation, while introducing an agent, actually reduces the total number of unexplained coincidences.

THE HISTORICAL IRONY

It’s worth noting that Ockham himself would likely be puzzled by the modern use of his principle. Medieval theologians regularly employed the razor to argue for God’s existence, seeing the divine as the most economical explanation for reality’s fundamental features. They understood true simplicity isn’t about having the fewest entities, but about having the most elegant and comprehensive explanatory framework.

ADDRESSING THE OBJECTIONS

- “But isn’t this just a ‘God of the gaps’ argument?” Not quite. There’s a crucial distinction between using God to explain current scientific puzzles and recognising God as the necessary foundation that makes science itself possible. We’re not saying “we don’t understand quantum mechanics, therefore God,” but rather “the very existence of comprehensible natural laws points to a rational source.”

- “Doesn’t this just push the question back—who created God?” This misunderstands the nature of the argument. The point isn’t that everything needs a cause, but that contingent, finite things require explanation in terms of something necessary and eternal. God, as classically conceived, is that necessary being—not contingent in the way that physical objects are.

THE RAZOR’S TRUE CUT

So is Occam’s Razor a compelling argument against theism? Only if we misunderstand what the razor actually does. Properly applied, it asks us to consider which worldview provides the most elegant, comprehensive explanation for the full range of human experience and cosmic reality.

When we sharpen the blade correctly, it may well cut away naturalistic assumptions rather than theistic ones. The medieval monk’s logical tool, it turns out, remains remarkably sharp—and it still cuts in the direction its creator intended. Perhaps the simplest explanation for why reality seems designed, purposeful, and rationally comprehensible is that it actually is.

OCCAM’S RAZOR: RELATED FAQs

What do prominent Christian apologists say about Occam’s Razor and God’s existence? William Lane Craig argues theism actually satisfies Occam’s Razor better than naturalism does. It provides a unified explanation for multiple phenomena that naturalism must treat as separate brute facts. Alvin Plantinga similarly contends belief in God is “properly basic” and doesn’t require the kind of evidential justification that would make it subject to razor-based elimination. Richard Swinburne famously applied Bayesian probability theory to show theism’s simplicity (as a single, unlimited substance) makes it more probable than complex naturalistic alternatives.

- Did medieval philosophers really use Occam’s Razor to argue FOR God’s existence? Absolutely. Thomas Aquinas, writing before Ockham, used principles of parsimony in his Five Ways, particularly arguing a First Cause is far simpler than an infinite regress of causes. Duns Scotus employed similar reasoning to argue for God as the most economical explanation for contingent existence. Even Ockham himself used his razor to argue against unnecessarily complex theological doctrines while maintaining God’s existence was the simplest explanation for reality’s fundamental structure.

- How do scientists today view Occam’s Razor in relation to religious belief? The relationship is complex and varies widely among scientists. Francis Collins, former head of the Human Genome Project, argues the razor actually supports theism when considering the fine-tuning of physical constants. However, many prominent scientists like Richard Dawkins contend evolutionary theory eliminates the need for divine explanation. Interestingly, some physicists like John Polkinghorne suggest the mathematical elegance underlying physical laws points toward a rational Creator, making theism the more “razor-friendly” position.

What’s the difference between Occam’s Razor and other principles of simplicity in philosophy? Occam’s Razor specifically targets ontological parsimony (not multiplying entities), while other principles focus on different aspects of simplicity. Leibniz’s Principle of Sufficient Reason demands explanations for everything, potentially supporting rather than opposing theism. The principle of theoretical simplicity in science favours elegant mathematical formulations over ad hoc explanations. Newton’s “hypotheses non fingo” (I frame no hypotheses) emphasised avoiding unnecessary theoretical constructs, which some argue actually supports the God hypothesis as foundational rather than constructed.

- How do Eastern Orthodox and Catholic theologians differ from Protestant apologists on this issue? Eastern Orthodox theologians like David Bentley Hart emphasise that God as “Being itself” transcends the category of entities that could be eliminated by the razor—God isn’t an additional being but the source of being. Catholic philosophers argue God’s absolute simplicity (divine simplicity doctrine) makes theism the ultimate razor-friendly position since God has no parts or composition. Protestant apologists tend to focus more on evidential arguments, showing how theism explains multiple lines of evidence more economically than naturalistic alternatives.

- Are there any logical fallacies commonly made when applying Occam’s Razor to religious questions? Yes, several. The “composition fallacy” occurs when people assume that because individual natural processes don’t require God, the whole system doesn’t require God. The “category mistake” treats God as just another entity in the universe rather than as the ground of being itself. There’s also the “false dichotomy” of assuming we must choose between either purely natural or purely supernatural explanations, when classical theism sees God working through natural processes. Finally, the “affirming the consequent” fallacy assumes that if naturalism were true, we’d see exactly what we observe, ignoring that theism predicts the same observations.

How does the multiverse theory relate to Occam’s Razor in debates about God? The multiverse theory creates a fascinating razor dilemma. Proponents argue it eliminates the need for God by making our universe’s fine-tuning statistically inevitable across infinite universes. However, critics point out that postulating infinite unobservable universes violates Occam’s Razor far more dramatically than postulating one God. Philosopher Robin Collins argues the multiverse hypothesis requires a “world ensemble generator” that itself appears fine-tuned, merely pushing the design question back one level. Many apologists contend that one designing intelligence is ontologically simpler than infinite material universes, making theism the more razor-compliant position.

OCCAM’S RAZOR: OUR RELATED POSTS

Editor's Pick

Self-Authentication: Why Scripture Doesn’t Need External Validation

"How can the Bible prove itself? Isn't that circular reasoning?" This objection echoes through university classrooms, coffee shop discussions, and [...]

Do Christians Need Holy Shrines? Why the Reformed Answer Is No

Walk into a medieval cathedral and you'll encounter ornate shrines, gilded reliquaries, and designated "holy places" where pilgrims gather to [...]

I Want To Believe, But Can’t: What Do I Do?

"I want to believe in God. I really do. But I just can't seem to make it happen. I've tried [...]

BC 1446 or 1250: When Did the Exodus Really Happen?

WHY REFORMED SCHOLARS SUPPORT THE EARLY DATE Many a critic makes the claim: “Archaeology has disproven the biblical account [...]

Does God Know the Future? All of It, Perfectly?

Think about this: our prayers tell on us. Every time we ask God for something, we’re confessing—often without realising it—what [...]

Can Christian Couples Choose Permanent Birth Control?

Consider Sarah, whose fourth pregnancy nearly killed her due to severe pre-eclampsia, leaving her hospitalised for months. Or David and [...]

Bone of My Bones: Why Eve Was Created From Adam’s Body

"This at last is bone of my bones and flesh of my flesh!" Adam's joyful exclamation upon first seeing Eve [...]

Is Calvinism Fatalism in Christian Disguise? Think Again

We hear the taunt every now and then: "Calvinism is just fatalism dressed up in Christian jargon." Critics argue Reformed [...]

Can Churches Conduct Same-Sex Weddings?

In an era of rapid cultural change, churches across America face mounting pressure to redefine their understanding of marriage. As [...]

Gender Reassignment: Can Christian Doctors Perform These Surgeries?

In the quiet of a clinic, a Christian physician faces a challenging ethical question. A patient sits across the desk, [...]

SUPPORT US:

Feel the Holy Spirit's gentle nudge to partner with us?

Donate Online:

Account Name: TRUTHS TO DIE FOR FOUNDATION

Account Number: 10243565459

Bank IFSC: IDFB0043391

Bank Name: IDFC FIRST BANK